Their Heads Are Green and Their Hands Are Blue: MDC

by Rebecca Firestone with Mark English AIA | Editorials

A correspondent from Mars visits the Monterey Design Conference. Who are these strange creatures called “architects”? Architects possess a unique language and culture all their own – a purpose and a place in the world.

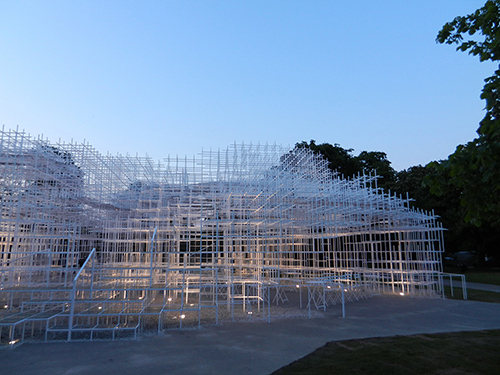

Images: Mark English Architects and Sou Fujimoto

As soon as my flying saucer touched down on the beach, I knew this was a different kind of place. My readers back home had been clamoring for more insight into Earthlings in general, beyond what they were getting on Netflix. “What’s with these odd-shaped structures?” they wondered. “Why is this building shaped like a barnacle?”

The FRAC Center in Orléans, France was designed by Jakob+Macfarlane. Dominique Jakob spoke at the Monterey Design Conference in October, 2017 and described this project among others. Photo Credits: Nicolas Borel and Roland Halbe

Martians are mainly practical folk, of course, and while a barnacle might survive our 600-mph windstorms, a building with a hole cut through the middle might not. It was a totally different mind-set. So they sent me, the Venusian half-breed, to the Monterey Design Conference in Pacific Grove, CA to find out what they were missing.

Headliners included, among others: Gere Kavanaugh; Sou Fujimoto; Dominique Jakob; Dorte Mandrup; Marion Weiss, FAIA; Michael A. Manfredi, FAIA; Jeff Goldstein, AIA; Shohei Shigematsu; and Julie Eizenberg, FAIA.

Unlike a lot of industry conferences, this one was fun for civilians. The architects were expected to attend the continuing education courses at 7am, but I just went to the design lectures – which were like going to a fascinating artist talk at a major museum, given by the artists themselves – a master class in design.

The conference took place at the Asilomar Conference Grounds in Pacific Grove, CA. Many of the original buildings were designed by Julia Morgan. Image: Mark English Architects

I Wear Loud Socks

Part artist, part engineer, part risk-taking visionary, part project manager: of all professions, architecture combines so many other disciplines. Social engineering as well. Their tribal costumes reflect this. On the one hand, form-fitted black tailoring with round glasses. On the other, stealthy dashes of color (gray) and colorful socks that no one actually sees.

My conference badge featured banners saying “I still hand draft” and “I wear loud socks”. That’s true even though I’m not an architect! Image: Mark English Architects

It’s as if the flair beneath is repressed, buttoned-down, concealed, controlled – because high-value clients aren’t going to trust a $100M project to an unkempt counterculturist as readily as they will to someone wearing a suit.

Ahh, Diversity!

Presenters included designers from around the U.S. and abroad. Women were well-represented. Anne Fougeron, FAIA, a prominent Bay Area architect, was on the selection committee for the conference, which was sponsored by the AIA California Council. I asked Anne how speakers were chosen, and she said, “Diversity… didn’t want another panel of all white males.”

Some architects at the conference favored the “whitescape” design philosophy, while others celebrated color. Left: Euro News Building in Lyon, France, designed by Jakob+Macfarlane. Right: N House by Sou Fujimoto.

One challenge is they don’t pay the presenters a speaker fee, only travel and lodging. That makes it harder to attract talent, especially talent from far away. “If you pay one person, you have to pay them all.”

What about presenter quality? “Well of course, that goes without saying.” And quality there was. I found the speakers lucid, practical, and highly original. There was a diversity of viewpoint, of projects, of scale, and of design philosophy. Even untrained, I could appreciate the coherence of the designs, and felt a sense of place.

Left: Ichihara public toilet by Sou Fujimoto, a functional art piece that is at once the typical Modernist “glass box”, and also a perfectly private walled garden, carefully screened from view. Right: Nabe restaurant in San Francisco, by Alan Tse together with Charles Chan Architectural Studio.

It’s actually quite a challenge filling out the speaker positions, as Anne Fougeron told it. “We wanted to be global, and it’s hard to balance. You get one Asian architect, then you have to re-adjust the remaining slots to get a different representation. It’s a chess game, you have to think 12 moves ahead.”

For those readers who aren’t architects, the designation “FAIA” means “Fellow of the American Institute of Architects”. It’s a highly coveted honor, bestowed by other architects, and only a handful of women have received it.

Audience Engagement

The talks weren’t overly theoretical, based purely on incomprehensible jargon and fantasy renders. Although, there was some of that too. Quite a number of the projects were already in operation, tangible, “real”. Presenters mostly focused on recent works, so some were in the late design stages, with expected completion dates within the next year or two.

The lectures had a storytelling aspect that gave them a broad intellectual appeal. Presenters described their own work, usually 5-10 major built works, and described their process – how did they get there? What tools or methods did they rely on? Where did they get funding? How did the project evolve as it went from concept to completion?

Conference attendees gathered in the sunshine in between lectures, outside of Merrill Hall at the Asilomar Conference Grounds. Despite the pristine skies, a long shadow from the fires up north in Santa Rosa hung over everyone’s mind. Image: Mark English Architects

There was a sense of friendly excitement and eagerness which conveyed itself to the participants through a general atmosphere of openness. A lot of the usual design-related standoffishness fell away in the small, intimate setting. A number of architecture students came, especially from schools like California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo. The dining halls had large group tables and very set meal times, forcing people to talk to strangers.

Saarinen Movie

One of the most interesting events was a movie showing. Eero Saarinen was a Finnish-born architect whose actual career had been cut short by a sudden cancer. The movie was made by his son, David Saarinen – who was also present and spoke on a panel right after the movie. Another way the past connected to the present.

No, Eero Saarinen was not at the conference. However, one of the presentations was actually a documentary movie about his life and work. This image shows the TWA terminal, which apparently sent the Modern architectural critics into fits at the time it was built.

Why was it so interesting? Saarinen’s forms, freeform as they were, had been created through old-fashioned model-making techniques before the days of digital CAD and 3D modeling. Saarinen’s life was almost as interesting as his career.

Permanence and Experience

Architects want to build monumental works that will out-live them, so that both their works and their own name will go down in history. Other forms of permanence and immortality include the preservation and transmission of knowledge. Changing people THROUGH places. Sometimes, architects want to playing God, while others stand in awe of nature (aka “god” or “cosmos”). Are we mastering the world, or preserving it?

Highlights

There were so many exciting projects that I can’t even remember them all. Predominant themes included environmental responsiveness, sustainability, playfulness, community-building, and human interactivity. Emerging Talent talks were 15-minute slots interspersed between the main speakers, showcasing younger designers.

Dominique Jakob of Jakob+Macfarlane had some colorful, shapely works. The built works shown were all in France. Her geometries reminded me of Min|Day Architecture, whom it would be nice to see at this conference as a presenter.

- Euro News Headquarters, by Jakob+Macfarlane. Photo: Roland Halbe

- Docks of Paris by Jakob+Macfarlane. Renovation and adaptation of existing waterfront structure

- Connected House by Jakob+Macfarlane. This private residence had to overcome neighborhood opposition, including a neighbor’s lawsuit. Even in France, apparently, it happens. There’s an underground swimming pool beneath the flagstones.

Jeff Goldstein of Digsau was grounded and practical, spoke about using the local history and designs of Philadelphia. Goldstein spoke at length about one of the jobs training programs, where local youths learn construction skills while building a rain screen for their own workshop building. Several of his projects featured extensive creative re-use of remaindered materials.

Matchbox by Digsau, in Philadelphia, a student facility. Note the stone facade near the base, a nod to Philadelphia local stone materials.

- Jeff Goldstein of Digsau spoke at length about a jobs training program. Here, 2 trainees are building a rain screen for their own workshop building.

- Delta Base Camp, by Digsau. This is a Boy Scout camp, mainly open to the outdoors, with gathering spots and sheltered areas.

- Detail of New Palmer Pittenger and Roberts Hall, by Digsau. Jeff Goldstein was very interested in the details of stonework, using traditional materials in modern ways.

Dorte Mandrup from Denmark showed an ice fjord glacier observatory and a sailing tower, among other works.

Ice Fjord Centre, by Dorte Mandrup. This glacier observatory, above the Arctic Circle in Greenland, had to address numerous environmental challenges including the world’s shortest building season and melting permafrost. The shape morphs like a Mobius strip, with the walls becoming the roof and the roof leading off onto the ground.

- Ice Fjord Centre, by Dorte Mandrup, shown here in the summertime. The first day the sun rises in January is a village-wide festival.

- Sailing Tower, by Dorte Mandrup. This is also an observatory of sorts, with plenty of ways for visitors to climb and explore.

- Sailing Tower, by Dorte Mandrup. The interplay of light through perforations creates a playful, sculptural effect.

Marion Weiss, FAIA and Michael Manfredi, FAIA of Weiss/Manfredi showed several outdoor parks and visitor centers. Their works were highly interactive with the outdoors, and they spoke at length about large-scale earthworks, water management, and other environmental necessities.

Brooklyn Botanic Garden Visitor Center in New York City, by Weiss/Manfredi. The smooth shape rises seamlessly out of the ground itself, and includes an all-season living roof.

- Hunter’s Point South Waterfront Park, by Weiss/Manfredi. This project featured extensive water management and flood control.

- Novartis Visitor Reception, by Weiss/Manfredi. Although similar in function to the Brooklyn Botanic Gardent Visitor Center, this project incorporates security features that aren’t necessarily visible in photos.

- Seattle Art Museum Olympic Sculpture Park, by Weiss/Manfredi. This was another extensive waterfront re-work, to showcase artworks against the heroic mountainous backdrop outside of Seattle.

Sou Fujimoto’s work had a futuristic, sculptural quality to it, with a lot of attention to the interplay of light through various latticework structures. He showed several pavilions and that famous Ichihara garden toilet! It worked, though, as a concept art piece. He was one of the “whitescape” designers. His N House is actually three partial shells enclosing one another. Another project was a condominium tower with a forest of balconies exploding near the top.

- Serpentine Pavilion by Sou Fujimoto, who is standing in the center. Although it looks like it’s made from PVC, the pavilion is actually assembled from steel pipe segments. (AP Photo/Lefteris Pitarakis)

- N House by Sou Fujimoto. Several interlocking shells with overlapping openings create the sense of a livable sculpture.

- Souk Mirage by Sou Fujimoto, a proposed landmark for a Middle East city that presumably had a lot of funding to spend.

Shohei Shigematsu of OMA (Rem Koolhaas’ firm) described numerous large-scale projects at top speed. He also had a mix of theatricality and large work, including exhibition designs. Some of his larger buildings had holes or cutouts – I couldn’t identify them online, but they were pretty cool.

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, exhibition for Man and Machine, a fashion and technology show, by Shohei Shigematsu

- Miami Beach Cultural District Faena Forum, by Shohei Shigematsu.

- Miami Beach Cultural District Faena Forum, interior, by Shohei Shigematsu. The lower interior and performance space features a large dome shaped like a nautilus shell – all white, of course.

Julie Eizenberg, FAIA of KoningEizenberg Architecture talked about affordable housing in Los Angeles, as well as a renovation and addition for Temple Israel in Hollywood, CA. Eizenberg was sensitive to local history and social justice issues in the renovation of a historically black YMCA building that now also offers affordable housing to a similar clientele – low and moderate-income people who are being priced out of ordinary housing. This phenomenon is happening all across California, and other parts of the U.S. as well.

- 28th Street Apartments, by KoningEizenberg Architecture. This adaptive re-use project was created from a historically significant YMCA building, with an addition in the rear. This view shows the original building in the front.

- Temple Israel of Hollywood, a renovation and addition by KoningEizenberg Architecture. The addition is shown to the right in the photo.

- Interior of renovation/addition to Temple Israel of Hollywood, by KoningEizenberg Architecture.

Alan Tse’s “Emerging Talent” talk was refreshingly candid. He spoke openly about project flaws (like water leaks in a spa) and how he dealt with them quickly. He mostly showed restaurants and multifamily housing projects. His designs embodied an interesting sense of space and bringing the restaurant out to the street in order to draw people in. The projects shown here are two locations for Nabe, a sushi restaurant in San Francisco, CA.

- Nabe sushi restaurant by Alan Tse, together with Charles Chan Architectural Studio. The restaurant ceiling extends out to the street, with an entry designed to entice people inside. This entry also makes the street experience more pleasant.

- Nabe sushi restaurant by Alan Tse, together with Charles Chan Architectural Studio.

- Nabe sushi restaurant by Alan Tse, together with Charles Chan Architectural Studio.

One of the other Emerging Talent talks featured Heather Roberge of Murmur. Her presentation was highly technical and blended advanced engineering and modeling with a beautifully polished-looking sculptural project titled “En Pointe”. In her words, “the mass and silhouette of each column is eccentrically distributed… While unstable individually, the columns enter a state of poise when grouped.”

En Pointe, Exhibition at the SCI-Arc Gallery, Los Angeles, California, by Heather Roberge of Murmur. The sculptures by themselves aren’t free-standing, which must have made the installation process a bit entertaining.

- En Pointe, Exhibition at the SCI-Arc Gallery, Los Angeles, California, by Heather Roberge of Murmur.

- En Pointe, Exhibition at the SCI-Arc Gallery, Los Angeles, California, by Heather Roberge of Murmur.

- En Pointe, Exhibition at the SCI-Arc Gallery, Los Angeles, California, by Heather Roberge of Murmur.

Theory vs. Grounding

Although most of the projects were based in reality, there was a smattering of annoying post-modern theory. Talk freed from action means you can say any damn thing because none of it really matters. Talking about cool futuristic stuff is whole a lot easier than executing something. For one thing, you don’t have to convince financial backers to build your project if it stays exclusively on the computer.

Execution means committing to one of many possibilities, which in turn means loss of the other possibilities, and likely a smaller first attempt than the earlier free-form flights of fancy. Prototyping, and failure, can be slow and agonizing. This can be very disappointing, and IMO is one of the hardest parts of “walking the walk”.

In one case, an entire project seemed to consist of “talking about community” and visions for the redevelopment of a dilapidated waterfront pier in San Francisco that has so many entitlements that nobody – NOBODY – has ever been able to build there. It’s a lot safer to stick to community meetings and pop-up projects than it is to actually commit to something permanent, and make that happen.

Nature

This conference underscored one aspect of architecture that is often overlooked: Nature. Of course, buildings are all connected to the ground in some way. A great building doesn’t just float in a vacuum. It interacts with, and alters, its surroundings. Beyond that, it alters the people who experience it, and this “experience” is something at once conceptual and immediate.

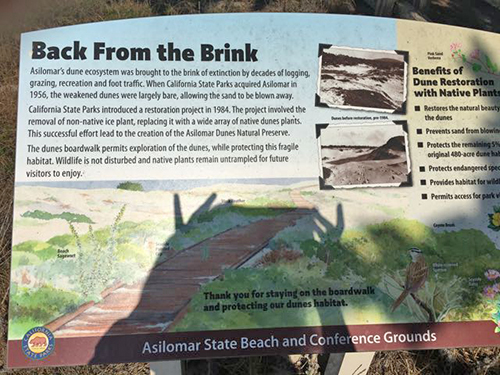

This beach sign at the Asilomar Conference Grounds describes the importance of dune and habitat conservation. Image: Mark English Architects

The site at Asilomar exemplified a type of extreme conservationism prevalent in CA and Southwestern states, where they’re so obsessed with habitat that you can’t even LOOK at a plant in case it gets frightened and disrupts a reproductive cycle somewheres. A lot of dead trees are left to decay because that’s natural, too. Dunes are very delicate and prone to erosion, so it’s not bad that they were so persnickety.

A shadow from the Santa Rosa fires hung over the place. Everyone was worried. A lot of people had lost projects, or their clients were in danger of losing their homes. The environmental destruction was sobering. One thing nobody disagreed on: climate change is happening, it’s real, and architects have to express this urgency through better, more sustainable design.

One of the vendors – who were present but not overwhelming – had a blues guitarist outside of their suite who was playing on a Fender guitar made from reclaimed wood. Vendors were, of course, easier for me to talk to plus they had free wine. Image: Mark English Architects

In fact, architects have a vital service to offer: rebuilding after natural disasters is not a theoretical exercise. It’s as immediate and practical as firefighting and emergency medical aid. Several architects mentioned that they had preserved the plans for their clients, which would help not only with insurance but of course with rebuilding. This tangible aspect of the profession also reinforced an overall sense of mission and shared purpose.

Collegial Atmosphere

Natural setting has influence, and this conference was relatively small, around 900 people. Not a giant “industry convention” at a hotel. It was an intimate setting that immersed us all in nature, and a friendly nature at that. No sleet! Not too hot, no poisonous snakes. Many architects said it wasn’t as competitive as other venues, more sharing of ideas, more support.

Progressives Fight Ignorance

It seemed like a given than nobody there liked the Trump administration or any of the ignorance and cruelty that it stands for. Not just about climate change, but war and persecution. Normally one might expect a spectrum of progressive and conservative views, but not here. Ignorance impacts design, especially for public projects. A lot of Jakob+Macfarlane’s work in France would get bogged down in community process if you tried to build it in San Francisco.

The Docks of Paris project by Jakob+Macfarlane exemplifies a type of civic boldness and taste that would be hard to replicate in the Bay Area. This project is a reclaimed old warehouse on the waterfront. Maybe San Francisco’s Pier 70 could take a few pointers, instead of blindly trying to preserve old corrugated shacks for “historic value”.

Planned to Death

Mark English had a few observations on the San Francisco planning process. After all, everyone’s done a master plan for the dilapidated waterfront area known as Pier 70, and yet nobody has ever gotten as far as building one single thing. “Bernardo Urquieta’s Pier 70 project is an example of what might have been,” Mark said. “By contrast, San Francisco’s Mission Bay campus was planned to death… prescribed building heights and every last little food place. Master planning all those details pretty much guarantees mediocrity. I’m not convinced that this is the right way to build a new neighborhood. It’s better to define the key places, the anchors, and then let the rest evolve organically.”

Image from a proposed master plan for Pier 70 from Bernardo Urquieta, AIA. This project won an AIA Urban Design Honor Award in 2009.

I was speculating with Mark about why it’s so hard to build anything, anywhere. We’ve written reams of articles about NIMBYism and how people will fight tooth and nail to preserve “existing neighborhood character”, even when that character is suboptimal.

How can people who consider themselves “progressive” not see how they, personally, are contributing to the ever-worsening homeless problem by allowing market shortages in the hopes that “all those people will just go somewhere else” and leave them alone? Yeah, they’ll go someplace else… they’ll start living under bridges. Even Google engineers are living out of their cars. That’s sick.

Monkeys Don’t Like Change

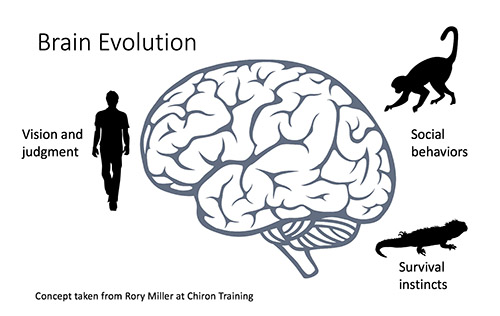

So… I finally figured it out. I got the answer out of a book by a law enforcement officer and self-defense expert named Rory Miller , titled Conflict Communication.

The social primate in us doesn’t like change, which is why neighborhood associations are so resistant to any sort of new housing going up in their area. Concept taken from Rory Miller’s Conflict Communication series. Image: Mark English Architects

What Rory says, more or less, is that the part of us that makes us social creatures (aka “monkeys”) is primarily interested in tribal identity, in keeping the group strong, and in everyone knowing their place within that group. For social hierarchies, any change at all is bad. It introduces uncertainty. People don’t know where they stand anymore. And this results in fierce social conflict, and competition for resources, until a new order is established. “The monkey can’t envision any change as being good… only humans can do that.”

So… this is why corporations form “diversity committees” that talk about change but actually work to preserve the status quo. And this is also why neighborhoods resist change, even when that change could be for the better, and could benefit them as well as any newcomers.

Notes

I riffed the title of this article from a book of travel essays by Paul Bowles, written in 1963. That title in turn is from a 19th century poem by Edward Lear, also a travel essay of sorts.

Far and few, far and few,

Are the lands where the Jumblies live;

Their heads are green, and their hands are blue,

And they went to sea in a Sieve.