Bernardo Urquieta: Drawing & Design

by Rebecca Firestone with Mark English AIA | Interviews

“Is there a right and a wrong in art that applies to everyone? Through sketching and observing, you discover for yourself the environment that surrounds and supports you. You create your own thoughts, your own personal ideas, your own experience, your own rules. I believe that this is the basis of human freedom.”

– Bernardo Urquieta, AIA

The Pens

“This one is from Italy, before the Second Word War. It has a fantastic flexible nib, which allows it to spread out. A great pen behaves more like a brush than a pen.”

Bernardo Urquieta was showing his collection of pens. Each pen had a story behind it. Mr. Urquieta, an architect of many years’ experience, described why he felt so comfortable thinking things out with a pen rather than a computer. “Hand drawing re-configures your brain patterns. It’s a faster way to think. It allows us to capture and discover the world around us in a unique and personal way.”

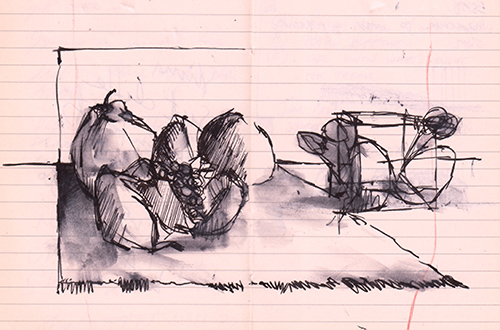

Neuroscience suggests that the physicality of hand drawing creates a sense of agency, or self-determination, that enhances both the designer’s own experience and the quality of the finished work. Image courtesy of Bernardo Urquieta, AIA.

Mr. Urquieta has had a long and distinguished career, beginning his practice in California in 1981, at the firm of Esherick, Holmes, Dodge, and Davis. He also worked with William Turnbull, Jr. Later he founded his own firm, BRU Architects, with projects including private residences, industrial facilities, resorts, and an award-winning master plan for San Francisco’s Pier 70.

Hand Drawing as an “Agile” Technique

Today’s tech world uses the concept of “Agile development”: nimble, cross-functional teams use daily scrum meetings and short, 2-week work sprints to create a series of working prototypes. Software developers can react quickly to new information, and refine the design more or less on the fly. While it’s usually applied to software, Agile development principles can be used for hardware as well – and, even architecture.

So, how is hand drawing faster? Mr. Urquieta related a story about one of his former employers, architect Joseph Esherick. Esherick was a reconnaissance specialist in World War II, flying over Japanese military operations in order to quickly detect the location and type of sea-going vessels. Escherick was the “scribe” or “sketcher”, in the days before drones, easy digital photography, or modern GPS.

As they flew overhead, Esherick strove to glimpse the Japanese naval deployments through brief and fleeting holes in the clouds. “The sketcher had to look only for things that mattered,” related Mr. Urquieta. “He had to work fast, using shorthand, to capture the number of vessels, the shape of the prows, and the number of stacks on each vessel. He would bring this intelligence back to base, and planes would launch the attack within an hour.”

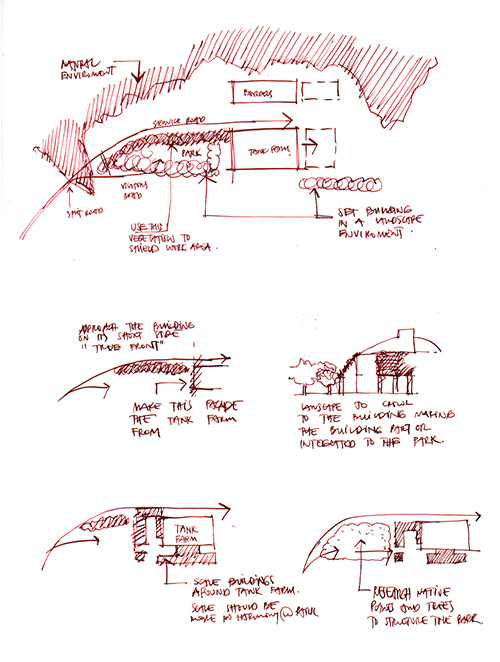

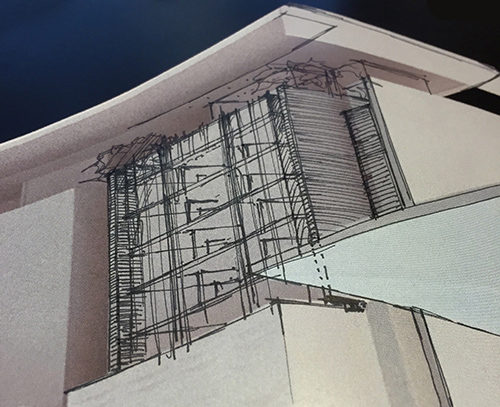

A process drawing allows for real-time response to a design problem, creating a palimpsest of current and previous iterations. Image courtesy of Bernardo Urquieta, AIA.

Why was this better than a photo? First, there wasn’t time to even snap a photo in the handful of seconds that the break in the clouds allowed. Second, a computer couldn’t produce that level of intelligence as quickly. “Photos are indiscriminate… there’s no analysis at the time that the image is taken. The analysis happens later, on the ground, by someone who wasn’t there.”

“A photo can only capture a reality outside of you. A sketch captures the reality inside and outside. When I sketch, both the analysis and the drawing are simultaneous, instantaneous. Sketching captures with both eyes and mind together.”

The Pen is Mightier Than The Computer

“In 1973 I was studying architecture, and one day I was sketching on a street. A guy started calling to me from a small booth – he sold pens and pencils, ballpoint pens. His fingers were blue with ink. He whipped out this old box and drew out a fountain pen. That’s when I started drawing with fountain pens.”

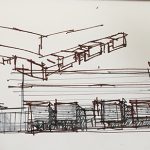

“With fountain pens, I learned that a line could have character. A line is not neutral. Drawing comes alive with a line drawn by a fountain pen. But it’s not as forgiving.” Image courtesy of Bernardo Urquieta, AIA.

Mr. Urquieta pointed me to a New York Times essay by Michael Graves on the importance of hand drawing and some of its playful as well as professional uses.

“The pen is wet and can smear. Drawing speed matters. If you want a thin line, you have to draw fast. There is a rhythm to drawing with a wet pen.” Image courtesy of Bernardo Urquieta, AIA.

- “Sketching is an act of selection and rejection. When drawing and observing, you have to identify what are the key the elements to bring out in your drawing, and how to see it in your head.” Image courtesy of Bernardo Urquieta, AIA.

- “As you draw, discovering, contemplating, observing, it forces you to notice things that otherwise you’d overlook completely. You enter the place through your discoveries. Over the years, this becomes the foundation of your own personal moral values.” Image courtesy of Bernardo Urquieta, AIA.

- Is there an optimal drawing speed? “Yes, there is a pace, a rhythm. A “zone”. The zone is where ideas flow just like water – fluid, transparent, and of immense beauty. The drawing takes on a life of its own.” Image courtesy of Bernardo Urquieta, AIA.

Drawing and Thought Process

“I’ve always been able to get a very clear vision in my head and then draw it out,” explained Mr. Urquieta. “I begin each day by laying out design problems on my table, something I have to accomplish that day. For example, I might begin with a render and lay a piece of trace over it. Then I take my dogs out to Crissy Field for a couple of hours. By the time I return, the drawing has figured itself out. It’s a very personal way to get into the ‘zone’.”

“Drawing mistakes aren’t failures. They can take you in a new direction. You need to listen to what the drawing is telling you. Your brain is always ahead of your conscious thoughts.” Image courtesy of Bernardo Urquieta, AIA.

Types of Sketches

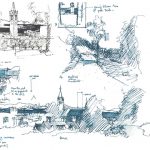

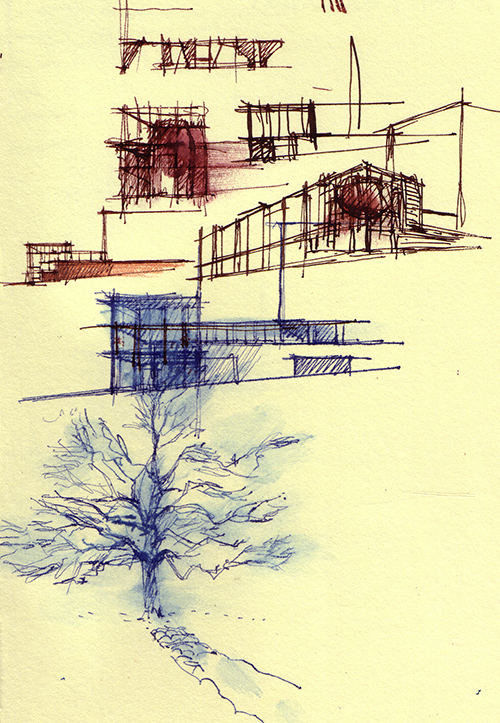

Different types of sketches happen at different stages of a design project. Environmental sketches come first, capturing the sense of place. After the general plan is established, hand sketches can help with hashing out the finer details, using trace over computer renders.

“Site sketches are a way to envision what could be built there. I use this as a trick, to start something new. These types of drawing are a layer or intermediary between reality and and imagination. The drawing starts as an intermediary and then it gets filled out. Drawing enhances your ability to think. The hand is connected to the brain in a very direct way.”

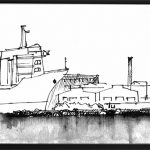

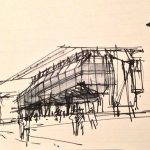

- “Observing buildings, as you draw, you observe EVERYTHING. As you draw, you are not even aware of it, but it’s being embedded into your brain. This type of drawing is for understanding the built world, rediscovering through your hand why this building is unique.” Image courtesy of Bernardo Urquieta, AIA.

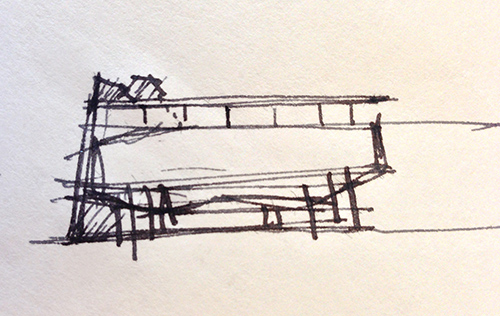

- “It starts out with a bunch of lines. Then the drawing reveals itself.” Image courtesy of Bernardo Urquieta, AIA.

- “It’s a playful game, to read the drawing. What is it saying? Where to take it? Instead of trying to force the drawing to conform to your initial vision, you have to let the drawing tell YOU what it wants to be. Listen to the drawing with your intuition. It will reveal personal thoughts of which you are not aware.” Image courtesy of Bernardo Urquieta, AIA.

- “Before designing anything, the first step is to draw the site as it already is.” Image courtesy of Bernardo Urquieta, AIA.

- “Sometimes you draw to envision things. Over the years, I’ve learned to trick my brain in order to draw out new ideas.” Image courtesy of Bernardo Urquieta, AIA.

- “This contemplative sketch shows male and female hummingbirds in our garden. I was not aware of how the sketch revealed gender through body language.” Image courtesy of Bernardo Urquieta, AIA.

- Image courtesy of Bernardo Urquieta, AIA.

- Image courtesy of Bernardo Urquieta, AIA.

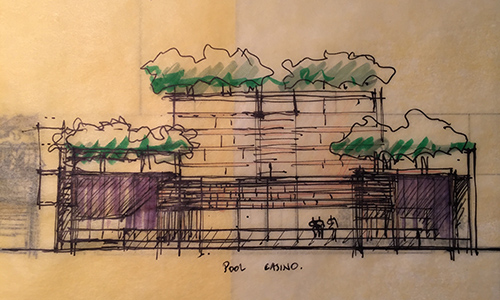

Hospitality Design

Our discussion touched upon hospitality design and how designing a large-scale resort could be related to home designs for private owners. “When you walk into an environment, either built or unbuilt, there is a response. A good design makes you feel good about yourself, the best you’ve ever felt, just by being there. The same feeling happens when you are in front of a great piece of art.”

“Many luxury hotels are over-built, flashy, visual pornography. But there’s a sloppiness of execution, because they think people won’t notice the cover-ups.” Mr. Urquieta employs the same attention to detail and craftsmanship from custom-designed homes and applies them at larger scale, to achieve the same effect: an elevated sense of happiness and well-being.

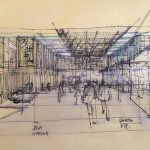

Good design doesn’t call attention to itself. Instead, it calls attention to the experience. Image courtesy of Bernardo Urquieta, AIA.

“I begin by imagining the experience that I want to create,” he said. “Not with forms or flashy gimmicks.” Oftentimes, this calls for a design with an inherent modesty, drawing attention to how people are feeling, and how they socialize within a space.“Capture the sense of place first.”

- “My architecture is Zen in its essence, but punctuated with baroque moments to elevate the spirit. All is incorporated: architecture, landscape, interiors, lights, music… a complete environment.” Image courtesy of Bernardo Urquieta, AIA.

- Image courtesy of Bernardo Urquieta, AIA.

- Image courtesy of Bernardo Urquieta, AIA.

Architect as Dream Keeper

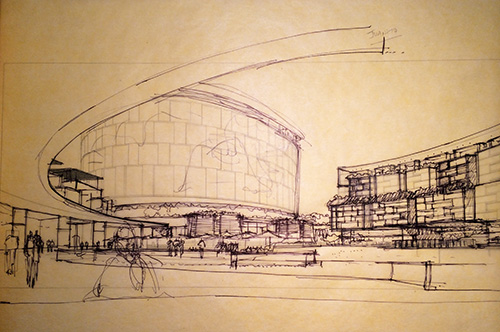

“On high-profile design projects, I serve as the ‘dream keeper’. I work to formalize the dream. The design is a series of small moments.”

It turns out that “thinking outside of the box” isn’t just for tech innovators. According to Mr. Urquieta, the concept originated during the Renaissance (see “Columbus’ Egg” reference at the end of this article).

Architects have to think outside of the box, too, and they start by questioning basic assumptions. “We wanted to re-invent hospitality by looking at a house as the nucleus of residential experience. Then you can build a great house, a house with 1,000 rooms for all your guests to have their own transformative experiences. What do guests enjoy? Lounges, sitting rooms, libraries… a series of little moments from an intimate scale to a large one.”

It’s good to have varieties of circulation between public and private as well. For example, guests who want to visit a hotel spa can walk over there without having to traverse great public spaces in their bathrobe. “No tortured forms,” he said. Instead, Mr. Urquieta combines intimate and mass experiences through the use of simple forms, elevated by “baroque moments” – accents or focal points that add interest to a space.

- Image courtesy of Bernardo Urquieta, AIA.

- Image courtesy of Bernardo Urquieta, AIA.

- Image courtesy of Bernardo Urquieta, AIA.

- In this Santa Clarita master plan for the city center Bernardo Urquieta emphasized “greening” of the court buildings. Image courtesy of Bernardo Urquieta, AIA.

Art’s Sense of Right and Wrong

At one point in our conversation, Mr. Urquieta mentioned art as having its own set of morals. “The word ‘morals’ in America has come to mean a narrowly defined set of sexual rules and behavior. I mean something completely different: morals as a philosophical term. There is a right and a wrong in art. Rules (i.e., morals) are typically given in architecture school. But when you draw and observe, the direct observation acts to form your own network [of associations and experiences] and eventually you have to formulate your own rules.”

Developing one’s own personal rule set is not just natural. “In my case, it was required as part of artistic development. You create your own rules from your experience… In my opinion, that’s the basis for all human freedom.”

Drawing Markup as Primary Communication Tool

Designing a large-scale hospitality complex is very different from designing a private home. For one thing, there are many more stakeholders to satisfy. A project has to stay on track, including entitlements, in order to retain investors’ confidence. Larger team sizes require more coordination, and teams may be globally distributed. Designing a home is a very personalized experience, with an understanding between architect and client that considers intimate details of how the clients want to live their daily lives.

“As your ideas evolve into a more sophisticated world view, so does your drawing.” Image courtesy of Bernardo Urquieta, AIA.

And yet, there is the desire to create that same personalized experience at a larger scale. This is often accomplished through thoughtful furnishings and interiors, and thus, the interiors team bears a great responsibility.

It helps to have high-quality teams. “When I communicate with interiors team, I want them to understand the design intent and support it,” said Mr. Urquieta. “The best interiors people in the world are a joy to work with. They don’t need a lot of explanations. I can communicate changes and explorations to them entirely through drawings, and trust them to carry it out successfully.”

Computer-Aided Design

Despite all the talk of hand drawing, Mr. Urquieta is not afraid of technology. “Quite the opposite! All tools are for the same purpose.” Technology integrates directly into the design process. For example, an interiors consultant might provide high-quality renders of a proposed design. This then serves as the basis for a new sketch, exploring alternatives or simply fine-tuning an already promising development.

Software tools include Sketchup and Rhino. This could be an expansion beyond more traditional digital tools such as AutoCAD, Vectorworks, or methods involving Building Information Modeling (BIM).

“You can actually design an entire house in Rhino.” Of course, more standard tools such as AutoCAD serve well during design development, permitting, and detail designs for construction. At a certain point, these tools become indispensable time-savers, and no one tries to design a large project entirely by hand sketching.

References and Links for Further Study

“Drawing and the Brain” Symposium

Today, the sketch remains an integral part of artistic inquiry, but has been all but supplanted in architecture by digital media. Though plans, sections and elevations are produced by the computer, the sketch is a tool of invention and discovery that requires the tactile involvement of the human hand and its direct relationship to the brain.

“What is the Impact of Drawing on the Brain?”, by Ana Mendes, September 5, 2016

According to neuroscience, the mind is not the sole producer of knowledge: the body also experiences emotions, which are communicated to the mind through the nervous system… emotions play an important role in the formation of knowledge, through the activity of the body.

“Architecture and the Lost Art of Drawing”, by Michael Graves, New York Times, September 1, 2012

“Drawing with a Purpose,” slideshow, by Michael Graves, New York Times, September 1, 2012

“Joseph Escherick, 83, an Acclaimed Architect”, New York Times, December 25, 1998.

“Thinking Outside the Box”, Wikipedia entry

“Egg of Columbus”, Wikipedia entry (early origins of “thinking outside the box”)