Gary Hutton: Becoming an Art Collector

by Rebecca Firestone with Mark English AIA | Interviews

“Start by educating yourself. Art should make you think, shake you up, see the world differently. Building the next great widget is a laudable task… But art speaks to the soul rather than the pocketbook.”

(Photo: Matthew Millman)

Start By Educating Yourself

“Start by educating yourself,” said interior designer Gary Hutton, when I asked him how an ordinary philistine of limited means could become a real art collector. “Choose a medium, a theme. Focus attention on that area and learn. Gain knowledge and understanding of the medium.”

“A Thousand Daddies”, a large-scale work by Mark Bradford, came out of his background as a gay, African-American man. Photo: Matthew Millman

Hutton is renowned, and revered, for his interiors that showcase serious art collections. His own fine-arts background informs his design work: he studied sculpture in college, working with such greats as ceramic artist Robert Arneson. His interiors are as carefully crafted, and subtle, as the artworks displayed within them.

He opened to a page showing around 600 sheets of paper tacked to the wall in one of Schreyer’s homes. “Mark Bradford is a gay African-American man. He grew up so poor that he had to draw on paper that fell from billboards, and every bus stop is plastered with flyers advertising legal services for child support. Every sheet in this artwork ‘A Thousand Daddies’ was inspired by similar types of these flyers.”

Collectors of Different Means

The sensational side of art appears in news stories where artworks are sold for astronomical prices, often during bidding wars at auction houses. It’s almost as crazy as Bitcoin. This implies that you need to be a billionaire to even think about investing in art. Not true! Anyone can do it – even civil service postal workers in a one-bedroom apartment, which is how Herb and Dorothy Vogel got started.

Herb and Dorothy Vogel collected over 4,000 works of art in their one-bedroom apartment – after donating that to the National Gallery of Art, they started over, and then gave away that collection as well. Image: herbanddorothy.com

The story of how the Vogels assembled one of the greatest collections of Modern and Minimalist art in the world is inspirational, as are the Vogels themselves: their humility, their dedication, and their overall friendly approach. They took classes in art history and also took studio classes, and learned how to paint and draw. They went to every art show and opening in New York City, spending literally all their free time.

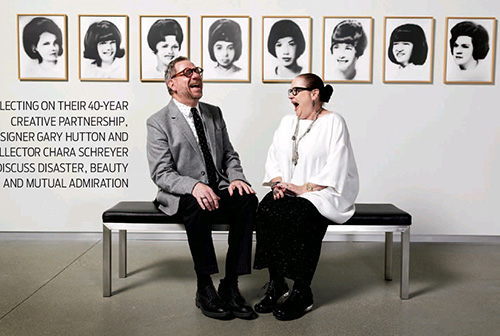

In contrast to the Vogels, who had humble means, Gary Hutton cited one of his own design clients, Chara Schreyer – whose 5 houses are the topic of Gary’s new book titled “Art House”. “It’s an extraordinary collection. She has the means to acquire whatever she wants.”

And, as it turns out, Schreyer is equally passionate about the artworks above all else. She has learned to embrace her own past as the child of Holocaust survivors in acquiring some very difficult and disturbing art pieces: serial killers, acts of violence, and other frankly transgressive pieces which she displays in separate “disaster rooms”.

Gary Hutton and Chara Schreyer in her “disaster room”, featuring art with tragic and difficult subject matter. Image: San Francisco Chronicle, April 24, 2016.

This particular room displays Gerhard Richter’s “Acht Lernschwestern (Eight Student Nurses)”, a series of oil paintings from yearbook photos of nurses murdered by serial killer; a portrait of Jacqueline Kennedy by Louise Lawler “Gold Jackie”; a collage of slashed nylon stockings by Bruce Conner titled “Night Lady”; the room is anchored by Richard Serra’s “Sparrows Point”, a bold black and white painting on the far wall.

Hutton cited frequently from the book as we spoke, using it as his textbook for a 3-hour master class in art appreciation. He quoted Schreyer from one of her house tours: “People collect psychologically and emotionally.”

Gary Hutton’s client Chara Schreyer’s background as the child of Holocaust survivors deeply informs her art collecting. “I understand that life can change in an instant.” Photo: Matthew Millman

Recognizing Great Art

So how does one recognize that presence of greatness in what might appear to be just a twisted hunk of metal? Is art universal? The debate over the universality of art is a long and fascinating one.

In addition to her “disaster room”, Schreyer has an “art shed” that includes a piece called “Broken Fence” by Hendrika Sonnenberg and Chris Hanson, an exact replica of a chain-link fence made from polystyrene and hot glue. Even in the photo it’s clear that this is an extraordinarily skillful execution. How did they do that?

An “art shed” designed by architect Timothy Gemmill for art collector Chara Schreyer. Artworks by Robert Gober, Jenny Holzer, Hendrik Sonnenberg and Chris Hanson. Photo: Matthew Millman

Art philosopher Denis Dutton suggests that evolutionary biology plays a direct role in our appreciation of beauty. In a TED talk from 2010, Dutton says that humans evolved to appreciate both beauty and skill – before they even evolved language. Beauty obviously signals fertile land and adorable offspring. But why skill? Because the visual evidence of skill indicates “desirable personal qualities” such as intelligence, fine motor control, planning abilities, conscientiousness, and access to rare materials.

Sound familiar?

Untitled works by Rudolf Stingel and Ned Vena show enormous levels of skill, dedication, and craft. One is sculpted Styrofoam, while the other is rubber on linen. Photo: Matthew Millman

Conceptual Art

OK, what about conceptual art, then?

A lot of contemporary art isn’t obvious, or beautiful. Sometimes it’s not even carefully crafted. Sometimes it’s never crafted at all, but remains an idea. I recalled Tom Wolfe’s satirical essays from “The Painted Word”. Wolfe actually said about a lot of art styles that “Without a theory, you can’t see the painting.”

Sol Lewitt’s art consists of a certificate that allows the buyer to hire his studio artists to come and install the piece. Interior design by Garry Hutton. Photo: Matthew Millman

- Sol Lewitt’s art gradually comes into focus as the viewer approaches. Interior design by Garry Hutton. Photo: Matthew Millman

- Once you’ve seen a Sol Lewitt piece like this one, you’ll recognize them in major museums as well. Photo: Matthew Millman

- A network of hand-drawn fine lines, created by Sol Lewitt’s own studio artists, installed onsite. Interior design by Garry Hutton. Photo: Matthew Millman

“Contemporary art is hot right now, meaning expensive,” Hutton observed. “A significant body of knowledge is required in order to appreciate it. It’s about the backstory, and understanding the artist’s thought process.”

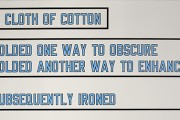

“People have to make a study of it, and understand its historical context. Otherwise it looks like just another Xerox.” Hutton showed me an untitled Robert Gober piece from Schreyer’s collection that looks like a pile of newspapers in a corner. “We refer to this as her recycling, but it isn’t,” he explained. “All the newspapers are printed on archival paper, and real articles are juxtaposed with artist images disguised as ads.”

Gallery space in Schreyer’s LA home. Robert Gober’s untitled newspaper piece is to the right, in the corner. Interior design by Gary Hutton. Photo: Matthew Millman

Hutton showed me a second Robert Gober piece. “Deep Basin Sink” is a handmade replica of an industrial sink, made to look exactly like the real thing. “This recalls a urinal piece from Marcel Duchamps in the 1920s. Duchamps was in essence saying, ‘Art is what I say it is.’“

Artist Robert Gober’s handmade replica of a sink gives itself away: where’s the faucet? Photo: Matthew Millman

Learn What Excites You

Gary Hutton did not provide a single road map that everyone should follow. Instead, he talked about passion. “Find art that excites you in some way, speaks to you. Art should make you think, shake you up, see the world differently.” In some ways, it means embracing what is difficult rather than what is familiar and comfortable.

I recalled a time when I the only one who showed up for a museum tour. “Take me to the art I hate,” I asked the docent. “I want you to tell me why it’s good.” At that time, what I hated was modern art. So, she and I walked through the Hirschhorn in Washington, D.C. I got a private master class… and felt a lot more comfortable judging art for myself afterwards.

“Art changes people,” Hutton said.

Difficult Art

Sometimes what makes it “art” is actually difficult or disturbing content. It’s transgressive in some way. If it’s too familiar, too comfortable, chances are it’s telling you what you already want to hear. It’s “decoration”. Nothing wrong with decoration… but that feeling of edginess, that emotional arousal, is perhaps one of the indicators that something interesting is happening right in front of you.

Hutton showed me some wallpaper in one of Schreyer’s homes. “Hanging Man/Sleeping Man” looks like an ordinary decorative 2-figure motif until you notice that one dark-skinned figure is hanging from a tree, while another figure is sleeping peacefully in bed.

“Hanging Man/Sleeping Man” by Robert Gober is a wallpaper. Interior design by Gary Hutton. Photo: Matthew Millman.

This piece evoked some strong disapproval online from people who didn’t understand the piece’s intention. Hutton recalled one particularly heated email exchange with someone who refused to accept that the artist could have had a conscious and positive purpose in creating such a disturbing image, when that was exactly the point.

Close-up of “Hanging Man/Sleeping Man” by Robert Gober. This artwork addresses difficult themes of racism and lynching. Photo: Matthew Millman.

Hutton had earlier mentioned Schreyer’s “disaster rooms”. Another difficult piece was a Jacqueline Kennedy portrait, from an iconic photo taken one hour before JFK’s assassination. “You know it’s before the assassination because she’s still smiling. And that’s the only time she ever wore that outfit.”

“The art is painted black on black, and it’s behind a black sheet of glass. You can barely see the image – but it’s still recognizable.” Placing these artworks in a separate gallery allows the original tragedies to be fully respected and honored. Another piece by Bruce Conner titled “Night Lady” is a collage of dark, slashed nylon stockings – evoking themes of violence against women, particularly prostitutes.

“When asked why she has such disturbing pieces, Schreyer responds that, as the child of Holocaust survivors, she understands that life can change in an instant, from things entirely outside of your control. She says it reminds her ‘How lucky I am’.”

The Light Bulb

How do you go about seeing a piece of art correctly? I asked. I’m sure we’ve all had eye-watering experiences, where we squinted at things that looked ordinary or featureless, craning our heads this way and that, wondering why the hell it was in a museum in the first place.

The string of light bulbs on the left is “Untitled (Tim Hotel)” by Félix González-Torres, a tribute to the artist’s friends who died from AIDS. Interior design by Gary Hutton. Photo: Matthew Millman

Apparently, there’s no one right way to gaze at art. Hutton talked about a light bulb going on. Sometimes this happens when seeing artworks in person, rather than in a book or a reproduction. Both Hutton and I learned to appreciate Picasso’s work after seeing exhibitions with large numbers of his works all in one place.

Speaking of light bulbs… Hutton spoke about one piece in Schreyer’s collection that’s just a string of light bulbs.

“It’s a spirit piece. The artist is Felix Gonzalo Torres, a Cuban boat person, a gay man, who lost many friends to the AIDs epidemic in the 1980s. This is about loss and recognition. Part of the agreement is you can hang it any way you want, but you can’t let any of the light bulbs go out. Chara has 300 spares in a box to make sure the piece always stays lit.”

Research the Artists

So, after finding what brings you joy, then what? “Find out as much as you can about the artist,” replied Hutton. “Learn about their chosen medium, and about other artists that this artist admires.”

Finding Art

So where do you get art? I asked. I mentioned having walked around many commercial galleries, not seeing anything that seemed edgy or new enough. Nothing disturbing. Maybe… I just didn’t hate it enough. If you drive up Route 1 along the California and Oregon coast, there are galleries with very pretty things, safe and conventional subject matter, intended to please a mass market rather than a discerning collector. Some of the merchandise, particularly the glass art, does have artist attributions and exclusive dealer representation.

It might depend on what you are collecting. “In the secondary art market, significant dealers are important. The Art Dealers Association is a good place to start. Any dealer who’s reputable will be a member.” Gary Hutton was addressing the question of authenticity and fraud. How do I know that Warhol is the real thing, and why would that even matter if that Brillo box is a replica? Wasn’t the original artwork a replica to begin with?

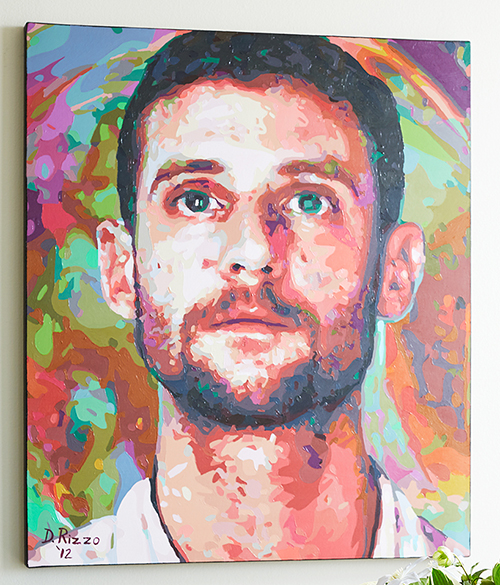

“Find something that’s under-appreciated.” Hutton talked about trends in the art world. Some 19th century American landscape painters could be had for a song 10-20 years ago, but not now. Hutton first saw one of his favorite paintings at a local pharmacy. Eventually he looked up the artist, and now has the piece in his own home.

The painting had an interesting backstory, too. “It was a mug shot of the artist’s own brother, a meth addict.” The eyes have a strange, otherworldly glow: as if someone of limited understanding were facing something supernatural, perhaps quasi-divine, for the first time – and wasn’t quite up to the task.

For recent or emerging contemporary artists, there are local complexes such as The Minnesota Street Project in the Dogpatch area of San Francisco, which hosts an entire cluster of local dealers and artists in a curated and supportive environment. There are open studios in places like Jingletown in Oakland. “The Richmond Art Center has juried shows every other year.”

Dealers play a role in the primary market as well, for top-name artists who are still producing, and whose works are featured in major museum collections. Many of these dealers will not even sell to private individuals. Why? One reason is that it’s not always good for the artists’ career to have their work disappear into private collections. Placing their art in major museums is not only more profitable for the dealer, but for the artist as well.

Stay tuned for Part 2, coming next week!