David Baker Architects: Affordable Housing, Slower Streets

by Rebecca Firestone with Mark English AIA | Interviews

Architects David Baker and Amit Price Patel discuss ways to make city housing and city living more effective, livable, and inclusive. For example, Lakeside Senior Apartments integrates low-income, formerly homeless, and special-needs seniors in a new 92-unit building in Oakland, California. (Photo: Bruce Damonte)

Affordable housing is like a dirty word. On the one hand, it implies free-market erosion caused by government meddling. In a practical sense, it means that someone with full employment should be able to rent a modest place without going into debt. And, in the Bay Area, “affordable housing” is increasingly an oxymoron and a vanishing dream, with 1 housing unit for every 10 jobs, gridlocked by a sort of over-entitled consensus democracy, driven by NIMBYism and fear.

What about populations who cannot survive unaided? Let’s say seniors with health challenges who are living on a fixed income, for example. If even a middle-class employed person can’t find an affordable place to live, how can we expect people with serious personal obstacles to do it?

And, are all government programs equal: Federal-level HUD-built public housing, state-run welfare programs, Section 8 vouchers, or private developers with tax credits? Should affordable housing be run by for-profit or non-profit entities? Should it be offered for sale or managed as a rental property? How do the buildings and people fare over time, and what makes it “successful” or a “failure”?

Posing the Questions

As part of the a lecture series titled “From City Project to Vibrant Neighborhood” for this year’s Architecture in the City Festival in San Francisco, we approached each of several potential panelists to ask them a series of questions related to housing and urban community life. Architect David Baker and his firm, David Baker Architects, have been building affordable housing for non-profit developers in the Bay Area for over 30 years.

“What does home mean to you?” is the theme of a 3-minute video documentary on the Dr. George W. Davis Senior Center and Residence in the Bayview neighborhood of San Francisco. Photo: David Baker Architects

Mark English and I sat down with David Baker and Amit Price Patel, both Principals at DBA. The firm itself is fairly egalitarian: nearly half the design staff, including one of the four Principals, are women. Several team members write for the DBA blog – which has a lot of original articles that are worth reading.

Based on that blog, I’d come up with a few starter questions.

Your housing projects emphasize building community through design choices, such as creating opportunities for residents to cross paths and interact in welcoming-feeling common areas. Other researchers such as William H. Whyte have promoted similar design practices for public spaces, making them more welcoming in order to enable social spaces and promote a sort of cosmopolitan mingling. But are formerly homeless people really ready to jump straight into apartment living? Can you really solve urban problems and social ills through design alone?

The Richardson Apartments in San Francisco, housing formerly homeless residents, is intentionally designed by David Baker Architects to foster social interactions by transforming the common areas into welcoming spaces. Photo: Bruce Damonte

Turning Housing into Home

Serving Special Populations

Amit Price Patel: Nonprofit affordable housing for special-needs populations such as formerly homeless people, or homeless seniors, usually includes a services suite onsite. It’s a one-stop shop to help them with a variety of issues, such as Social Security paperwork, VA benefits, psychiatric issues, or physical disabilities. Otherwise they’d have to go downtown and deal with the bureaucracies unaided.

On-Boarding New Residents

Rebecca: In some cities, like Syracuse, NY, they are welcoming large numbers of refugees from places like Somalia and now, probably, Syria as well. It seems like these groups might have culture shock as well as trauma. How quickly can they acclimate to new surroundings created with the design techniques you advocate in “9 Ways to Build Community with Urban Housing“.

Amit Price Patel: It might take a while for some groups to really settle into their new homes. In these affordable housing buildings, there’s some level of “settling” as well. It might take residents a few years to acclimatize and really be able to take advantage of the social spaces, but it’s important to provide them with the possibility of engagement.

Bayview Hill Gardens maintains a visual connection between the entryway and the plantings in the interior courtyard area. Photo: Bruce Damonte

Diversity Within Buildings

David Baker: Diversity helps a building to thrive, meaning a mix of special-needs residents and “mainstream” people. However, it’s not done as often because there’s an impulse to serve where the need is greatest first. “Housing first” is the motto, because people aren’t able to deal with their other problems effectively until they have a secure place to live.

Amit Price Patel: Buildings that are dedicated to formerly homeless populations do have a more intense vibe… there’s more pain. Oftentimes, physical disabilities are part of this pain.

Amenity Spaces Improve Any Building

Amit Price Patel: Affordable housing often has higher density than ordinary apartment buildings, meaning the units are smaller. Thus, shared spaces are crucially important. However, even in luxury apartment buildings, amenity spaces such as lounge areas get used. It’s kind of a networking or co-working opportunity, like at Potrero 1010.

DBA’s Potrero 1010’s 453 units include 90 affordable homes. The shared amenity spaces include a welcoming lobby, resident lounges, and conference rooms.

Affordable Housing as Rental Market

Amit Price Patel: Non-profits don’t like to build 3-bedroom apartments, because a lot of the families who’d live in them would prefer to squeeze everyone into a 2-bedroom and save that extra $500/month rent to put towards other things, like college, or clothes, or food.

David Baker: The prevailing business model today is either a private developer or a non-profit group, building properties that they then rent and manage.

Affordable Housing, Then and Now

David Baker: Affordable housing was done by the [Federal] government until Reagan was in office. Then, the GOP started a movement to privatize affordable housing through a tax credit system. “Kill HUD” was their motto. Later, the GOP conveniently forgot that the tax credit system was their own idea, and now they’d like to kill the nonprofits.

Amit Price Patel: Affordable housing is just for low-income people. There are plenty of middle-class households that can’t afford luxury housing, but they can’t get into the subsidized homes because they make too much money. It’s also because the wait lists are so long.

Competent Housing Developers: Who’s Good?

David Baker: If I had to list the agencies I feel are really competent, it would be under 10. It’s a mission-driven business, where economies of scale help. We are currently working with a long-time collaborator, BRIDGE Housing, and a new client, Mission Housing Development Corporation, on an affordable family project, and it’s going great.

Planning

Planning Boondoggles

David Baker: We should make the San Francisco planning process rules-based [by-right] rather than capricious [discretionary review]. Establish reasonable standards and then follow those rules. Building new housing should not be a multi-year journey. We need predictability and fewer points where people can stop a project. Buildings would cost less and be better designed, because you’d have money to spend on those essentials rather than wasting it on endless bureaucracy.

Amit Price Patel: Planners are there to represent the community’s desires, but also need to be empowered to nimbly deal with long-term housing and transportation crises, and focus less on things like deck additions and blocked views.

NIMBYism and Petty Tyrants

So why are lines for even market-rate rentals out the door?

David Baker: The logjam is the result of a whole confluence of forces: NIMBYism, bureaucracy, and people who fear changes such as fewer parking spaces on their street or renter displacement. There’s also an “I’ve got mine” sense of entitlement from multi-million dollar condo owners who are complaining that “San Francisco is too dense” and saying “We shouldn’t build here.”

Amit Price Patel: To paraphrase Daniel Solomon, San Francisco is stuck between love and hope. People already here love their city and don’t want change. But, all these people are coming in with the hope for a better life, and there aren’t enough housing options. We’ve just got to build more because people aren’t going to stop coming to such a great city with so many jobs.

This proposed affordable housing project at 1950 Mission Street, designed by David Baker Architects, is the first 100% affordable housing to be developed in San Francisco’s Mission district in a decade. Image: David Baker Architects

5 Years To Approve One Project? Seriously?

David Baker: A typical multi-unit housing project takes 5 years to get approved in San Francisco, and that’s if you’re lucky.

Amit Price Patel: Individuals are allowed to have a disproportionate impact on planning projects. It takes forever to get projects approved with the discretionary planning reviews. At any point in that process, a single cranky citizen can derail things for another year with a simple filing fee.

Role of Tech Companies

Amit Price Patel: Companies are somewhat constrained by where their employees want to be. SalesForce was building a huge new campus and then discovered that its employees really liked being right downtown. So they cancelled the new campus and just work with a series of downtown buildings, building a new tower.

Curran House, located in the Tenderloin area of San Francisco, is affordable family housing designed by David Baker Architects for the Tenderloin Neighborhood Development Corporation. Photo: Brian Rose

Amit Price Patel: The high cost of housing means that tech companies can hire only very young people who are willing to live out of their cars, if that’s what it takes, or in compressed dormitory-style living. Or, they can hire senior VP-level types with the salary to afford market rates.

David Baker: Some tech companies are, in fact, starting to invest in housing and other infrastructure improvements. At times, they are running into the same NIMBYism in Mountain View that plagues similar housing approvals in San Francisco. Google wanted to build housing in Mountain View – nixed. Google wanted to stripe bike lanes on the streets in Cupertino – nixed. In other parts of the country, there’s more room for this. For example, Under Armour in Baltimore is building worker housing AND new police stations.

[For great discussion of the infamous Google buses and the Bay Area housing shortage, see “How Burrowing Owls Lead To Vomiting Anarchists (Or SF’s Housing Crisis Explained)” ]

Benevolent Dictators

One of Amit Price Patel’s blog posts described how the city of Medellin in Colombia rapidly transformed itself under a dynamic and active new mayor.

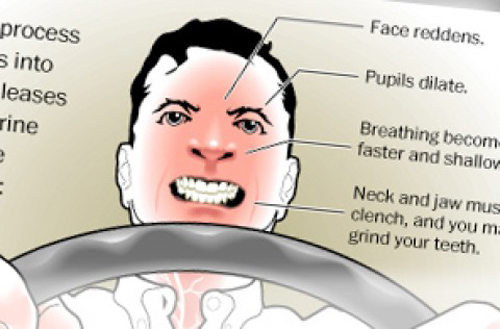

Bulb-outs are curb extensions configured to slow down fast-moving vehicular traffic so that bikes and pedestrians can more safely share the road.

Amit Price Patel: There’s an expectation of politicians in Medellin – build it, and do it quickly. They’re also willing to experiment, and to try prototypes. For example, trying paint markings on streets to see how they affect traffic flow. We’re doing that here to some extent: experimenting with bulb-outs, parklets, and the whole Pavement to Parks initiative.

Transit

Privatized Transit

Rebecca: One reason people want to live close to the action is that it’s hard to get around the greater Bay Area without a car due to a disjointed patchwork of transit systems. BART, MUNI, Caltrain, and various buses all require re-entry and sometimes walking several blocks between stations.

David Baker: Privatizing transit could work. Chariot [a crowdsourcing commute app] could be a competitor for MUNI. Right now, MUNI has a monopoly. A century ago, most transit companies were private. Tokyo’s rail system today is private.

Amit Price Patel: Uber, Lyft and other ridesharing services are good. Let a thousand flowers bloom! Uber is forcing cabbies to be nice and take your credit card instead of cash. Uber gets you home after a late-night party when BART is closed.

David Baker: Autonomous vehicles are the future in cities. They’re not *allowed* to hit you!

Shared Streets

Amit Price Patel wrote a blog post about India’s shared streets. All sorts of moving entities from pedestrians to buses, all moving at varying speeds – more lanes and thus more carrying capacity, but generally slower. During our interview, he remarked, “The concept of jaywalking as an offense dates from the 1920s when cars were running people over. No one was used to the higher speeds. Jaywalking is actually a denigration of pedestrians.”

[One reason why traffic should slow down is for cyclist and pedestrian safety. For example, on June 22 of 2016, two cyclists were killed in a single night in separate hit-and-run accidents. Drivers were going too fast and driving recklessly – proposed solutions included better police enforcement, as well as dedicated bike lanes or “share the road” markings. Physical road features such as bulb-outs are intended to force drivers to slow down before accidents occur, regardless of whether they’re caught by police afterwards.]

Amit Price Patel describes India’s street traffic flows: “it’s a much more equitable street. There’s more capacity. Everyone has to pay closer attention. Everyone has to go slower.” Photo: David Baker Architects

[Medium.com has a list of cyclists killed by drivers in San Francisco since around October of 1996, including factors contributing to the crash. It’s an informative but alarming read.]

Shared streets can have markings such as “Sharrows” for “share the road with bikes”. Safer yet are dedicated bike lanes, often color-coded green to make them more visible.

Home

What Does “Home” Mean To You?

David Baker: It’s the place you live. Not private places isolated from one another, but a spectrum of private to public space. I see a lot of people I know on BART!

The Q Zone

David Baker: Most people experience buildings at the ground level. They don’t care how many stories are over the cafe. Developers want to build up to the property line in order to squeeze out that last square foot of rentable floor space. But, you can instead use setbacks to create a gracious and inviting ground floor. That’s what the Q Zone is about. The “Q” is for Quirky – the place where a building is personalized.

Amit Price Patel: Don’t try to “solve” a problem – because you will fail. You want to make it easier [for people to be social], and encourage “possibilities”.

David Baker will be a panelist on a forum September 22, 6-8 as part of the Architecture in the City Festival. Tickets available at Archandcity | Lectures

2 Responses to “David Baker Architects: Affordable Housing, Slower Streets”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Craig Hamburg | The Architects' Take

18. Oct, 2016

[…] our housing panel, which featured Tiny House advocate David Ludwig, affordable housing architect David Baker, housing advocate Sonja Trauss, architect Anne Fougeron, FAIA, City Planner David Winslow, as well […]

MASP: A Brazilian Masterpiece | The Architects' Take

01. Feb, 2017

[…] architects talk more in terms of the urban form and landscape, how buildings relate to one another. David Baker may be one […]