Minnesota Street Project: Ecosystem for the Arts

by Rebecca Firestone with Mark English AIA | Editorials, Interviews

“If we don’t do something soon, there won’t be an arts community in San Francisco at all. It’ll become a city of millionaires and homeless people.”

– Andy Rappaport, co-founder

“If we don’t do something soon, there won’t be an arts community in San Francisco at all. It’ll become a city of millionaires and homeless people,” said Andy Rappaport, during an AIA-sponsored walking tour of San Francisco’s Dogpatch neighborhood on September 8th, 2016. At that time, the Minnesota Street Project had just opened up as a brand-new type of enterprise: an organization offering economically sustainable spaces for galleries, artists, and related nonprofits, funded by a full-service fine-art storage facility.

- 1275 Minnesota St. houses ten charter galleries, spaces for temporary exhibitions as well as a restaurant and Atrium designed for public programs and select private events.

- 1240 Minnesota St. houses 35 private artist studios as well as shared resources and workshop space.

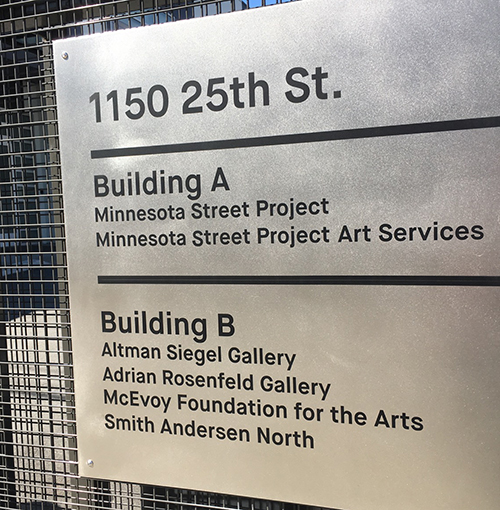

- The building 1150 25th St. offers climate-controlled art storage, which is intended to serve as the financial backbone of the project in order to keep gallery space and studio rents affordable.

Ecosystem

The other part of the walking tour included a presentation by designing architect Mark Jensen, describing the architectural interventions necessary to convert 3 formerly industrial buildings into code-compliant public-access facilities.

Right across the street from 1275 Minnesota is a parklet maintained by a vast consortium of local acronyms.

- Parklet at Minnesota and 24th Streets in San Francisco.

- New housing and apartments across the street from 1275 Minnesota.

- A more typical street scene in Dogpatch with a mix of existing industrial buildings and some new housing.

The idea is to create an entire ecosystem, so not only the art production, but sale, storage, and shipping all occur within the same complex of buildings. Within the studio building, there’s a lot of communal space to encourage real-life social contact, including shared amenities such as a well-equipped kitchen in the studio building, ADA-compliant bathrooms, a kiln, a computer and printing room, and various viewing rooms. The Rappaorts seemed to thoroughly understand the nature of being an artist and how important it is to have a supportive community environment.

Both the Rappaports and Mark Jensen stressed over & over that arts communities have to be in close proximity; they can’t be scattered or exiled without an epicenter. The first thing that sprang to my mind was co-location, the lost art of actually working in the same physical space as your colleagues.

All this “ecosystem” talk is also part of the new urbanism that architects and planners in San Francisco are promoting. Things like living alleys, walkable cities, inviting public spaces that encourage social contact, getting people out of their cars and their gated communities to participate in a public life filled with civility and goodwill.

Project History

The Minnesota Street Project is the brainchild of Deborah and Andy Rappaport, two dedicated art collectors with a philanthropic bent. The walking tour was narrated by the two of them, as well as the designing architect Mark Jensen. Andy Rappaport is a high-tech venture capitalist – just the sort of person we were asking “Why don’t these tech bros do something useful for the rest of us?” and while the Rappaports weren’t talking about housing specifically, they were talking about how real estate markets have displaced not only artists, but galleries and art dealers as well.

They leveraged some of San Francisco’s zoning rules for the Dogpatch neighborhood, which allow for light industry and artisanal skilled trades, but specifically disallow office space. This provides some protection from displacement due to tech boom and bust cycles. Some prior experience in San Francisco real estate served them well: they got this project approved and built in under 2 years.

1275 Minnesota has a reception area and a stair, leading to mezzanine galleries above. The main atrium runs the entire length of the building.

- 1275 Minnesota Street used to be a furniture warehouse.

- The renovated central atrium at 1275 Minnesota preserves much of the original structure, with the new structure as a light overlay.

- 1275 Minnesota Street in 2014, prior to renovation.

The walking tour was two years ago. Last week, Mark English and I met with Frank Merritt from Jensen Architects to review the architect’s side of things. Mark Jensen, FAIA is well-known for his work with other art spaces, from single artist homes up through museums.

Jensen’s work is elegant, spare and minimal. Flexibility and economy were core design principles. The huge central corridor in 1275 can host everything from art auctions to select private events for civic, corporate or charitable events.

“1275 was first,” Merritt said. “Both artists and galleries were being expelled by high rents. The Rappaports were already part of the arts scene. They felt that they had to do something, or the entire San Francisco arts community would disappear.”

“The building had a cathedral-like feel. It was more about not messing it up,” said Merritt. The galleries share communal amenities and infrastructure, with a common reception area, kitchen, storage, and shipping/receiving area.

Towards the rear of 1275 Minnesota, the atrium terminates in a series of bleachers, where visitors can sit and hang out, listen to lectures, and view their surroundings.

- Bleachers are built around existing structural elements.

- The architect paid attention to making this highly visible ductwork express symmetry as well as functionality.

- Existing structural components were carefully fitted into new elements with a minimum of fanfare… but not just cramming it into a blank wall, either.

Simplicity

“We designed it for the fewest number of moving parts,” Merritt continued. Much of the existing structure was left intact, and newer seismic beams were inserted where needed. Outer walls were strengthened with Shotcrete, with shear walls dividing up the galleries.

- The structural elements added during renovation are thicker than the original steel supports.

- Shotcrete encases additional structural elements and blends in with the original poured concrete features.

- The original elements were cleaned up, but not prettied up.

Art Studio Building

The 1240 building houses 35 artist studios. It’s curated, meaning the artists and galleries all had to apply for space and undergo vetting. Out of 300+ applicants, there are 35 private studios, plus additional shared resources available to service approximately 80 artists working in the Bay Area.

- Entrance to 1240 Minnesota.

- A typical artist studio in 1240 Minnesota. They’re not overly large, although larger than comparable spaces in the Torpedo Factory in Alexandria, VA.

- Join detail from original beam, left intact.

Shared amenities include various workspaces, kitchen, a group exhibition space, a digital media room, and a kiln.

The studio building is a little less sleek than 1275, but still rigorously finished even as raw plywood.

- The same plywood construction used throughout provides a unified design feel.

- Common work area for things like screen printing.

- 1240 Minnesota includes a kiln.

Art Services

So, how’s all this financed? Somewhat to my surprise, it’s NOT a non-profit. Being a nonprofit was too cumbersome. You can’t be nimble. Deborah Rappaport serves on a lot of nonprofit boards, and spoke about it at length during the original walking tour. Instead, the Minnesota Street Project is a for-profit, break-even enterprise, supported by a division called Minnesota Street Project Art Services, housed in the third building at 1150 25th Street.

The brochure reads as follows:

“Minnesota Street Project Art Services provides museum standard, one stop storage, installation, transportation, and collection management solutions for private collectors, galleries, and institutions. Our select team of experienced art handlers, registrars, warehouse and shipping managers, and client services personnel deliver a level of customized and comprehensive service not otherwise available in the Bay Area.”

The viewing room at 1150 provides a space where art consultants, art dealers, and interested clients can view potential art purchases together.

Business Focus

Andy Rappaport’s entrepeneurial background informed a lot of the business decisions and gave them a certain amount of confidence. He had a solid grasp of value/risk as it applies to physical, tangible buildings. Deborah also has a background in marketing and branding, which has helped them to promote this project.

1150 includes several additional galleries, such as Altman Siegel, which have shows that are open to the public.

- Altman Siegel had a show up for artist Trevor Paglen.

- Artist Trevor Paglen’s show at Altman Siegel Gallery. This piece is a facsmile of a proposed art satellite.

- Altman Siegel Gallery at 1150 25th Street in San Francisco.

Andy had some interesting things to say about the tech companies and their people. Why aren’t the tech millionaires patrons of the arts? Well… millionaires are, in other cities. The financiers of Wall Street, the moguls of Los Angeles, many of them are in fact collectors and patrons of the arts. The San Francisco tech guys, not so much, due to the lack of arts education in American public schools. “They’re all so new they don’t even know what to do with their money,” he said.

There are benefits to being involved in the arts world as well, even for the self-serving. Sitting on the boards of arts organizations and nonprofits is a great way to meet senior executives at your own and other companies, because they sit on those same boards.

Artist Constance DeJong’s sound installation work in “Stories” shown at McEvoy Foundation for the Arts, at the Minnesota Street Project.

- McEvoy Foundation for the Arts, at the Minnesota Street Project, has a “great room” which feels both grand and calming.

- Acoustical treatment at the roof and upper walls helps clear the exhibition room sound.

- In a side gallery, acoustical treatment on the drop ceiling.

What was interesting is that Deborah told me they started out as collectors of very modest means. “The first art piece Andy and I ever bought together, cost us $75. That was a month’s worth of groceries to us.”

Links

- Minnesota Street Project, About page

- Mark Jensen, architect

- Minnesota Street Art Services

- Trevor Paglen, artist

- Artspace magazine interview with Andy and Deborah Rappaport, March 27, 2016

Mark English, AIA

25. Apr, 2018

Type your comment here…