Collections Strategies for Design Firms

by Rebecca Firestone with Mark English AIA | Other Voices

How do you handle it when your clients get behind?

“Call them up!” says Michael Bernard. Don’t push this task off onto your bookkeeper. If the client writes the checks, the principal should make the call. “Keep your voice neutral and unemotional. Rehearse beforehand if you need to. The message is that, as a small business, cash flow is vital to your operations, and you’d appreciate them sending an immediate payment.”

“One former client felt so guilty about a tardy payment that he paid up even to his current charges that hadn’t been billed yet!”

[ This article was written in conjunction with Michael Bernard, our “Ask Michael” columnist, and is the continuation of our previous article on billing for smaller architectural firms. ]

In our previous article, we described a few billing basics: what should be on the bill, and how to use the contract as a vehicle to establish all appropriate relationships and responsibilities. Having good understandings in place from the get-go is the best aid to keeping your accounts current.

Even so, Murphy’s Law is well-known, and you can’t depend on documentation to prevent every mishap. So, how do you handle it when your clients get behind? “They sure don’t teach this in architecture school” is what I found out – but the good news is, all is not lost, as long as you have the will to act on your own behalf.

Traditionally, collections has been viewed as a strong-arm profession, but a real professional can do better.

Collecting Late Payments

If you do a Google search for things like “collections letters” or “collections practices”, you’ll find a wealth of material, mostly advising people in debt how to fend off aggressive and unethical collections agencies. You won’t find too many call scripts or sample letters, at least I didn’t, and none that would be suitable for a professional services firm.

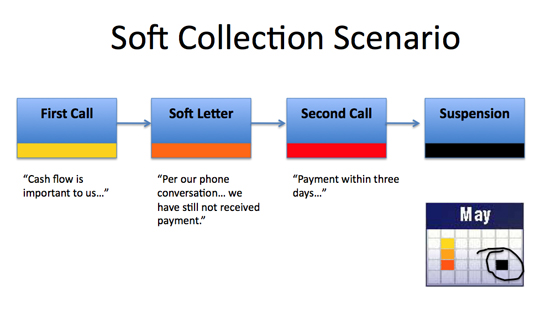

However, you will need some consistent process to follow, and it should consist of a series of actions and escalations such as calls or letters, that are most likely to yield the results you want. It can be personalized to each client, but don’t let any of your clients off the hook, because the slack you cut others will come back to cut you.

Client is unusually late? “Call them up!” says Bernard. “Keep your voice neutral and unemotional. Rehearse beforehand if you need to. The message is that as a small business, cash flow is vital to your operations, and you’d appreciate them sending an immediate payment.” If you end up leaving a voice message, mention the hardship and then ask the client to call you or send payment immediately.

Should you have your bookkeeper make these calls instead of doing it yourself? “If your client is an institution or other large organization, the bookkeeper or project manager can make the call. If the client writes the checks, the principal should make the call.”

What about a timetable? Most collection action scripts include one or two phone calls and a series of letters from “soft” to “stern”. You might have to consider what works for you and your clients, but whatever you decide, be strict in sticking to timetables. If the client is on 30-day payment terms, you can make your first call on day 31. “Again, just keep it neutral. You’re calling because you haven’t received payment on the last invoice – for small firms, cash flow is vital, your business depends on it, and you would greatly appreciate prompt payment.”

If You’re Not Paid, You Can Cease Work

The next step if a phone call doesn’t work is to cease work and notify the client. Again, the contract is your ally, and it should contain language including fees to resume a project, and the conditions under which a stop-work order can be issued. If you make a second phone call, this can be the “serious” call where you inform them that you will be forced to cease work on their project, that this will affect the entire team and the project schedule, and that both payment in full plus an additional fee to resume work would apply. Sometimes clients don’t realize the true cost of delays in terms of permits that expire, or other factors.

[ This is not the same as a “stop work notification” in a legal sense. Here, ceasing work on a project means re-allocating your staff to other tasks, telling them not to bill any more hours to the project in question, and not spending any more of your own time on the project other than to archive the work as it exists to date. If the client requests the architect to cease work, there’s usually a specified number of days that the architect can still legally bill for cleanup. By contrast, a stop work notification is a legal action that obligates the construction lender, if there is one, to withhold funds to cover the outstanding fee. ]

Keep a record of ALL your calls and conversations regarding collections.

Arbitration and Mediation

The design services agreement is a de facto notice of right to place a lien. With the right to lien as leverage, the contract confers the right to mediate and/or arbitrate later on down the road, if it is needed.

Carrots and Sticks

I asked Michael Bernard how well these “soft” calls actually worked. I used to think that collecting was an uphill battle unless there was some immediate leverage – if you don’t pay me, I won’t submit your project at the Building Department – but Bernard again advised on lining things up from the beginning was the best way to avoid adversarial situations.

“A former client felt so guilty about a tardy payment that he paid up even to his current charges that hadn’t been billed yet! But to obtain this outcome, you have to lay the groundwork early, and set up those terms long before.”

Having said that, there are two points in the project that are good times to true up the accounts, and that is right before submittal, and right before construction. You can also pull the permit out of Planning so that construction can’t go forward without you. Choosing to take such a strong measure can be a very nerve-wracking decision, but even if you do end up resorting to it, don’t think of it as a hostility so much as putting your foot down to set some limits on the treatment that you will accept.

Do you ever charge late fees? I asked. “A late fee can be added to the contract as leverage, but I’ve never had to charge one. Usually reminding the client that late payment penalties COULD apply is enough.”

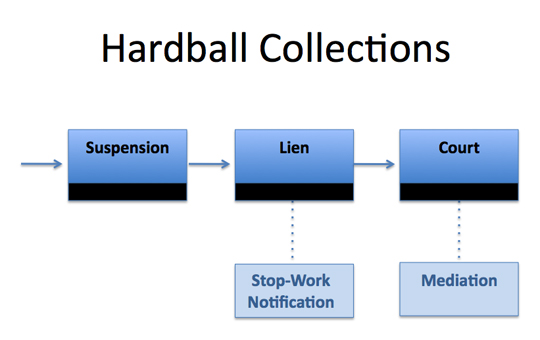

If all your best efforts fail to get results, you can put a lien on the property. Optionally, a stop-work notification can be sent to the construction lender. If you end up going to court, many contracts provide for mediation as an alternative.

Legal Recourse

When we got to this portion, Michael Bernard took the time to share with me a handout that he had received from Severson & Werson, a law firm that provides legal services for architects here in San Francisco. Much of the information in this section has been distilled from one of their “First Friday” workshops which Michael Bernard attended.

"A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush," meaning that cash received today is better than promises of payment later.

So you’ve called, you’ve written, you’ve pleaded, you’ve not only threatened to cease work but you’ve actually notified everyone and re-assigned your staff. What’s next? A lot of architects go straight into writeoff mode, although some will just leave these debts open in their books for years. Either way, that’s money left on the table.

Some architects don’t want to play hardball because they’re afraid of making their client angry. But then you have to ask yourself: What are you realistically getting out of the situation as it stands today? Are you fantasizing that this one big commission is going to win an award someday? Are you hoping that the client will work with you again? But if you’re not getting paid now, why do you think the client will pay you the next time? Michael Bernard puts it this way: “If you’re not getting paid, what does that say about the value of your services?”

“Architects are professionals licensed by the state along with other professions such as engineers and contractors,” notes Bernard. “This means that they have some legal recourse that is not available to other design professionals such as interior designers.” This recourse consist of liens and stop work notices. A lien applies to the property, and a stop work notice obligates the construction lender, if there is one, to withhold funds to cover the outstanding fee. For design professionals, there are two types of lien, depending on whether construction has started or not.

However, none of this will do you any good without a signed contract. There’s a bunch of fine print here (in 18 point Powerpoint type) about contract fees vs. reasonable value of services, and some important schedule limitations. You have to prove that you’ve delivered the services, that you’ve invoiced for these services, that you haven’t egregiously overcharged for your services, and that you’ve formally demanded payment. Also note that liens only work if the client who owes you money is the actual owner of the property.

After reading the rest of this presentation from Severson & Werson, I’d only say that getting a lien requires a lot of attention to detail, paperwork, process, and timely scheduling. Sometimes you have only 10 days or 20 days to complete an action. So, if you do pursue this route, make sure you allocate appropriate staff resources as well as your own time to keep track of where you are in the process. But, the good news is, you HAVE this recourse, and it has been successfully used by professionals like yourself who have the fortitude to commit to it.

Finally, if none of this works, you can resort to arbitration or take your client to court. Obviously this is something that none of us ever wants to do. Some architects may be afraid that their professional image will suffer, but I’d opine that unless you make a habit of litigation, the only people it will deter are other problem clients. These situations can and do happen to everyone from time to time, and if you let people walk on your bones, all that will happen is you’ll sink deeper into the hole.

Conclusion

But relax, all is not lost. There is a light at the end of the tunnel. Bernard sees the tasks of billing and collections as occurring within the larger context of running a design-centered business.

“We face so many risks in day-to-day architectural practice: liability, design excellence, quality of product and so on. These areas easily command our attention. Compared to these challenges, billing and collections should be a lead-pipe cinch. Yet we sometimes lose sight of the importance of cash flow in the name of pursuing more stimulating design-related activity. If we ignore the importance of a clear, lean and rigorous system of billing and collection, we will slowly but surely compromise the health of the very entity that allows us to pursue the career we love.”

Billing is only one of many tasks in running a design-centered business, but with care and attention, our tranquility won't be disturbed by needless hardship.

Severson & Werson Contact Information

Severson & Werson gives free workshops on the first Friday of every month to interested design professionals. To obtain more information, or to request a copy of the presentation referenced in this article, please contact Pete Molgaard at 415-677-5626.