Arcosanti: Why?

by Rebecca Firestone with Mark English AIA | Editorials

“It’s legendary within urban planning and architecture as a utopian idea… and yet it seemed sad. A failed experiment. It’s romantically inspired, but It’s not an appropriate response to the climate. Unlike the original Pueblo settlements, it’s not self-sufficient.” (Images: Mark English)

– Mark English, AIA

“It’s legendary within urban planning and architecture as utopian idea, one of many, where people formed intentional communities.” Mark English had recently visited Arcosanti and was sharing his impressions. “It’s a very sad place. It’s poorly sited, no natural shading from landforms. It’s not an appropriate response to the climate.”

Arcosanti is an experimental “urban laboratory” outside of Phoenix, AZ. Image: Mark English Architects

- Originally envisioned by Italian architect Paolo Soleri in the 1970s, Arcosanti remains active today. Image: Mark English Architects

- Living quarters at Arcosanti. Image: Mark English Architects

- Image: Mark English Architects

Architect Paolo Soleri had started it up in the 1970s as an experiment in “arcology”, or a combination of architecture and ecology. Like so many before them, he thought his experiment would ultimately inspire a new dawn of human civilization.

I felt a stab of guilt. It was like criticizing Buckminster Fuller, or Gandhi. But progress requires us to review the past with clear and unbiased eyes, assessing what worked, and what did not.

Arcology’s premise was to create entirely self-sufficient places, similar to futuristic domed cities or biospheres. There were grand plans at Arcosanti for 5,000 people. Today, it’s got around 180 residents, with an interesting program that includes events, concerts, lectures, coursework, and an ongoing cottage industry making hand-cast bronze wind chimes. People can visit, participate, stay overnight.

Design Issues

So what exactly was wrong with it? I asked Mark. “It’s poorly sited, no natural shading from landforms. It’s not an appropriate response to the climate. There’s no real attention to solar orientation or shading. It’s not like the Brazilian modern buildings we’ve written about, with their emphasis on simple non-mechanical devices like brisé soleil, solar alignment, and overhangs. Here the buildings are facing south, with no overhangs.”

“Other Modernists like Le Corbusier knew how to design these structures.”

But Soleri was Italian. Don’t Italian buildings have features to handle sun and heat? Soleri was Italian, true – but not a traditionalist. “He brought over a lot of Aldo Rossi-inspired stuff.” Aldo Rossi was a famous postmodernist, and his buildings are pure form. “This building has no loggias, no shaded walkways to protect from sun and rain.”

Pueblo Architecture Comparison

Mark compared Arcosanti with some of the historic Pueblo Indian structures that he’s visited in the American Southwest. “Ancient human settlements were always near a water source, so that the inhabitants could reside and grow food all in one spot. Arcosanti is near a seasonal creek that is dry for half the year. No crops are grown there. There’s a McDonald’s just down the road. It’s not self-sufficient.”

Native Pueblo settlement in Arizona, situated in a natural apse on a cliffside. Image: Mark English Architects

- Historic Pueblo settlements were near a natural source of water and arable land, making them self-sufficient. Image: Mark English Architects

- Natural Arizona cliff formation. Image: Mark English Architects

- Pueblo structure situated underneath a natural rock overhang. Image: Mark English Architects

“The building is shallowly inspired by what’s already there in the American Southwest. But it’s not shaded. It’s south facing, with no overhangs or fins to break the sun’s heat. It’s form-driven rather than climate-inspired.” Speaking of climate, I had wondered about the non-native deciduous tree in an Arizona desert, and the grass. Didn’t Soleri know about xeriscaping, and low-water plantings?

Arcosanti’s landscaping includes non-native deciduous trees and cypresses. Image: Mark English Architects

- mage: Mark English Architects

- West facing facade windows could have used shading overhangs. Image: Mark English Architects

- Shored walkway at Arcosanti. Image: Mark English Architects

“It’s very interesting in one sense, as an architectural response to creating a new way of living in nature.”

Living in Nature

“Arcosanti is a romantically inspired vision,” Mark observed. “The Pueblo settlements are another example of humans living close to nature, with better use of existing landforms and planning. The native peoples took advantage of natural apses in the sheer cliff face. A typical settlement consisted of a dwelling in a cliff, with farmland and river in a valley beneath. It was self-sufficient, and defensible as well.”

- Arizona Pueblo settlements were accessed by ladders, as shown in this ancient ladder petroglyph. Ladders could be taken up for defensibility. Image: Mark English Architects

- Pueblo structure. Image: Mark English Architects

- Cliff dwelling offered some natural defenses, as well as protection from the sun’s heat. Image: Mark English Architects

Most of the Pueblo sites are now closed to the public, but Mark was able to enter one years ago, and described the layout in detail. “In this cliff face there are 6 layers to the Pueblo. Horizontal workspace was at a premium. People got up there using ladders, like the one in this cave drawing.”

Arcosanti clearly hadn’t had to think about defense. All those utopian domed cities, self-contained and self-sufficient, sounded to me like medieval city-states.

What’s It Like To Be There?

“It’s a very counterculture vibe. A circus-y, heavy metal crowd. Very white… they’re all white.” Like the Burningman crowd? I suggested. “Yes… Burners that actually make stuff. It’s almost religious in a way. Monastic. There’s even a bell tower that calls people to dinner, just like a real monastery.”

“What was great about it was that the people attending all got involved with the building process. This was a Frank Lloyd Wright principle too. Wright’s studio, Taliesin West, was also an outpost in the middle of nowhere.”

Structure known as “The Vault” at Arcosanti is a double arch, open on both ends. Image: Mark English Architects

There were a few buildings that seemed suitable for a desert – large shaded structures, domes and arches. “You can actually work under this dome during the day. They were casting bells the day I was visiting, with the heavy metal music cranked way up.” Yep, Burningman. Sounded like fun to me, actually.

What Would You Do Differently?

So what would YOU build out there? I asked Mark.

“I would respond more to the climate. The sun’s intensity. Compare it to an ancient city like Jericho. The Arcosanti terrain is flat, with a ravine. This building is perched right on the edge of that ravine. And if the idea is to create a whole city-as-building, self-contained, small footprint… why is it a suburban layout with architectural showpieces spread around?”

What about that dome? I hazarded weakly. I had rather liked the dome, and the idea of casting metal handicrafts to the sounds of heavy metal music out in the desert. “Its archaeology porn. Made to look like a Roman ruin.” Geez Mark, way to harsh my buzz.

What about that double arch? “It’s similar to a structure in Iraq, the Taq i Kisra or Kisra Arch. But their interest in ‘archaeology’ is about the look of the form. It’s not all that deep.” This ancient structure was a monument, or part of a city… perhaps not useful, but certainly awe-inspiring.

Shaping Community Through Design

Mark wondered, “Can you really make a community out of this? I’m just responding from my personal impressions. It seemed sad. A failed experiment. One that most people would not want to engage in.” If Arcosanti is a community, it must have living quarters. Would you want to live there? “No. It’s too harsh, too exposed. It feels isolated, too small.”

We’ve explored before whether it’s possible to change society through design alone. For example, the greening of cities through parklets and interactive public spaces, and David Baker’s affordable housing designs with features that foster positive social interactions between building residents to help them feel part of a community.

What makes public spaces feel inviting and safe, rather than hostile and dangerous? Elijah Anderson’s book “The Cosmopolitan Canopy” describes public spaces in Philadelphia that, through some miraculous alchemy, brought about an atmosphere of civility and goodwill. But, is that enough?

Utopia and Tribalism

If success is achieving one’s stated goals, then if this one failed, which of its own goals did it miss? Was it the utopian aspect? I suggested to Mark that the opposite of utopia was dystopia. Was it dystopian? No. “If you don’t care, don’t know anything different, there’s no dystopia. There’s no nightmare.”

We talked about other housing dreams that became re-cast as nightmares, especially American public housing. Ben Austen’s recent book High-Risers presents a detailed narrative history of Chicago’s Cabrini-Green housing project. It was striking how many of the long-time residents were fiercely loyal to the place, considering it home – due to strong social support networks that became all the more important in times of adversity.

Burningman is also an experiment of sorts, a temporary city. “Burningman is not a model for a real physical community,” Mark noted. “But it is a tribal phenomenon. To live in a place like Arcosanti, you have to want to belong to a tribe. Most people don’t want to do this… To make a real community, you need all kinds of people, age and cultural diversity, wise elders and excited youths, believers and non-believers.”

Black Rock City, a temporary city built for the Burningman art festival every year in Nevada. The city is always constructed in a circular pattern. The Man burns in the center.

This idea of remaking all of civilization isn’t just utopian, it’s apocalyptic. “In theory, their new civilization was universal. In reality, it was composed of people who all believed the same thing.” Very much like a monastery, in fact. (Burningman, however, is not a monastery.)

It seemed to me that in any new intentional community, the social and leadership structures were important. The design aspect could reinforce those structures in various ways, depending on how the community intended to operate. However if that leadership were ineffective, or oppressive, no amount of design can compensate for that.

I also thought of the Bauhaus movement, a very hands-on, communal existence combining art, craft, architecture, and shared communal purpose and identity.

Urban Density

Mark cited a “Core Values” blurb from Arcosanti’s web site “A Limited Footprint”.

“urban density as opposed to unbounded dispersion allows more activities in less space and better use of limited resources providing access for all to the economic and social essentials of ‘city’ life”

Mark noted: “Their principles were interesting. A limited footprint, or urban density, is what we’re still thinking about today. We are thinking about the cost of resources and getting away from suburban sprawl and car culture. People like millennials are returning to urban settings. So, are these models worth thinking about again? What can we use? A place like Arcosanti could serve as a proving ground for certain things.”

A Dream Confronts Reality

Paul Gustafson was an engineering student in 1982 when he wrote an article about Arcosanti titled “An Architect’s Dream of the Future Confronts Reality”, published in Future magazine in March of 1982. Soleri’s density goal was 215 people per acre. That’s per acre – not per square mile. (Most density statistics appear to be in either square miles or square kilometers.) At 640 acres per square mile, that’s 128,000 people per square mile. According to Wikipedia, Manila is the is the densest city in the world, at 107,561 people per square mile.

Other high-density cities include Mumbai, Dhaka, and – surprisingly – a town of 15,000 people in the Marshall Islands. There was also a squatter city called the Kowloon Walled City, which had 33,000 people in a single city block until it was razed and replaced with a park. (No stats on density per acre or by square mile.) While density does have its advantages, the actual quality of life might be rather different from what Soleri had envisioned.

Gustafson wrote: “A major part of [ Soleri’s ] theory suggests that man has not yet reached his highest stage of evolution… According to Soleri, Arcosanti sets the stage for the “cultural explosion” of the human race.” Utopian visions aside, evolution means change. This change doesn’t always bring an improvement, because Nature is essentially impersonal. Then I remembered John B. Calhoun’s famous rat population density studies, where he came up with the term “behavioral sink” to describe behavioral pathologies stemming from over-crowding.

Mark English notes, “Even Soleri’s contemporaries questioned the vanity of the endeavor.” Gustafson quotes several engineering and architecture professors at the time, including Wesley Shank, who was Professor of Urban Design and Architectural History, Iowa State University:

“With dense population comes confusion, noise, and lack of free space. [ Soleri is ] not working closely enough with social science people… The value of what he does kindles imagination… but he seems a bit carried away with his vision, it’s beyond practical means… his hypothesis needs to be checked. To follow theory without small-scale experimentation is both dangerous and foolish. Soleri’s ideas provide direction, but the actual application lacks technical knowledge.”

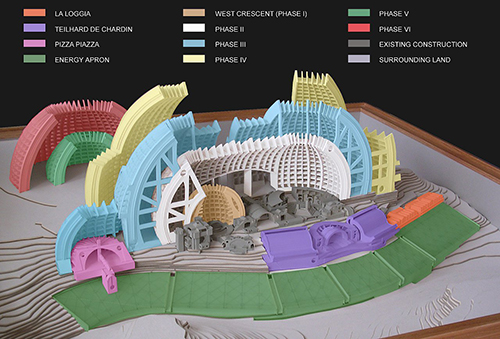

Soleri wasn’t practical about fundraising, either. Most of the more ambitious physical structures have yet to be completed, even today.

Arcosanti color-coded model. Existing construction is dark gray. All other structures are unbuilt. Image: Arcdhaily, through Arcosanti.org

A Positive View

A thoughtfully written Motherboard article about Arcosanti from 2017 presents a more positive view of the place, with some eloquent perspectives on Soleri, ecology, advanced city designs, and humanity’s future.

The scale is pretty different, though. Even at 5,000 people, Arcosanti would still be a tiny fraction of the size of, say, New York City with 8.5M in the boroughs and 20M in the greater metropolitan area. There’s probably a reason people who want to build new civilizations isolate themselves geographically.

Despite all the criticisms, I wanted to go out there, I told Mark. It looks exciting!

Links and References

- Wikipedia entry on Arcosanti

- Architect Paolo Soleri, Wiki

- “Arcology” = architecture + ecology, Wiki

(Densely populated, but low-impact environmentally) - Arcosanti organization, program and information

- Arcosanti’s sales site for their bells

- Brazilian Modernism on The Architect’s Take

- Aldo Rossi Wikipedia entry

- Florentine architecture

Images: Palazzo Medici Riccardi and Palazzo Piccolomini – loggias - Kisra Arch, Wikipedia entry

- David Baker interview on The Architects’ Take, on affordable housing

- Elijah Anderson’s book The Cosmopolitan Canopy

- High-Risers, Ben Austen’s book on Cabrini-Green

- Burningman web site

- “An Architect’s Dream of the Future Confronts Reality”, Paul Gustafson, 1982

- Densest cities, Manila

- Kowloon walled city Wikipedia entry

- Kowloon was a squatter settlement

- The Guardian: What is worlds densest city, advantages and drawbacks

- Rat population density, behavioral sink, Wikipedia

- Motherboard article on Arcosanti

- “City in the Image of Man”, a slideshow on Arcdhaily, from Arcosanti.org

Arcology and its first child : Arcosanti – Project Kaizen

30. Nov, 2020

[…] Architect’s take : Arcosanti : Why ? […]