Craig Hamburg: Developer, Citizen, Urbanist

by Rebecca Firestone with Mark English AIA | Interviews

“I’m disappointed that housing is so often treated strictly as a commodity… Designs should be impactful, not relying on cheap materials or bloated buildings. Developers aren’t the same as speculators. Developers are in it for the long-term…

“Context matters, too. My vision for San Francisco is to have great public transportation with higher density around the transit hubs, and get more cars off the road.”

(Photo: 400 Grove St., San Francisco by DDG, design by Fougeron Architecture)

I first heard about Craig Hamburg from Mark English, who was putting together a housing panel for the AIA’s Architecture in the City Festival this past September. “What? A developer who’s actively promoting good design in San Francisco?” We first thought of him while discussing the role of the Hayes Valley Neighborhood Association (HVNA) in formulating and promoting the Market Octavia Plan

which, among other things, turned a formerly freeway-centric area into a green and walkable mixed-use community, with several new multi-family housing projects.

450 Hayes Street is a new multifamily housing project in San Francisco from DDG, with design by Handel Architects.

First of all, it’s amazing that any project of that size made it through a politically contentious ten-year battle over whether or not to rebuild the earthquake-damaged Central Freeway.

Second, the most vocal obstructionists to building new housing often seem to come out of the local neighborhood associations, who’d rather die than see ANY new housing built in their private fiefdoms. And they are often no friend of Modernism, preferring to preserve the past at the expense of the present.

At last, new-construction with a loft-like interior that still looks like a real living space. 450 Hayes, by DDG with Handel Architects

All this does is drive housing costs through the roof, and those who are already there can say, “Well, I’ve got mine. Go live somewhere else, even if you have to drive two hours to get to your job.” Hence our housing panel, which featured Tiny House advocate David Ludwig, affordable housing architect David Baker, housing advocate Sonja Trauss, architect Anne Fougeron, FAIA, City Planner David Winslow, as well as Craig Hamburg, who has collaborated with a number of the panelists on various projects.

DDG is Not Your Typical Development Company

Unlike many other developers, who seem to be in it only for the money, Craig Hamburg and DDG, the firm he works with, seem to be genuinely interested in promoting the greater good, rather than packing the city with overpriced fake “lofts” featuring tiny footprints and cheap facades.

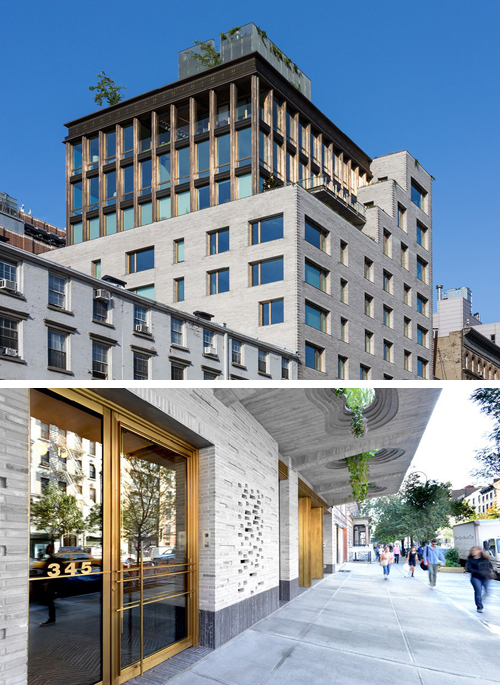

DDG’s high-end buildings in New York, San Francisco, and Florida all show a commitment to state-of-the-art housing with an emphasis on environmental responsibility: rooftop gardens, bicycle parking, bio-retention programs (stormwater treatment), keyless entry, virtual doormen, LEED certifications. One of the New York buildings, 345 Meatpacking, is LEED Silver, and some of the San Francisco projects are underway for becoming Greenpoint Rated. In their portfolio, about a third of them have won design awards in California or in New York – multiple awards, in some cases.

The XOCO 325 condominium building at 325 Broadway in NYC, shown in context. The granite-gray colors help to knit this building’s surrealist Gaudi-like sensibilities together with the surrounding buildings, also recalling the types of granite and slate found in New York State. By DDG.

“I didn’t plan on becoming a developer,” Hamburg said. “I had wanted to be a doctor, because science and biochemistry were fun.” Later, at Tulane University, he majored in finance instead. “A finance degree would make me more flexible.” After graduation, he worked for a developer-builder partnership and learned about building and construction.

The interior of XOCO 325 references local context in other, more subtle ways: hexagonal bath tiles are a familiar sight in many older New York buildings. Here, the tiles are elongated and done in a dove-gray marble that also echoes the New York local stone types. By DDG.

As a developer, Hamburg’s mission is “creating places that engage both residents and the community” – through context, density, and proximity to public transportation. A recurring theme at the AIA Housing panel was actually opening up buildings to the street, moving away from gated developments that cut off people from their neighbors, moving away from car culture, and creating more opportunities for people to mix in public spaces that are pleasant, walkable, and safe.

What does “Home” Mean to You?

What does “home mean to you? I asked the other panelists. It’s what happens outside your front door. It’s being able to walk in my neighborhood and see people I know. Knowing that my kids can safely cross the street. Biking to work, or stopping at a local coffee shop to catch up with my neighbors. Home is a communal experience.

400 Grove Street in San Francisco, looking up. Each floor juts out at a different angle, providing each apartment with its own unique viewpoint. DDG and Fougeron Architecture.

David Baker spoke about creating floor plans that encouraged residents to cross paths within a building, and by having lobbies and workspaces that encouraged people to get out of their homes and hang out a little. David Winslow spoke about Linden Alley and other “living alleys” – a New Urbanist offshoot designed to transform concrete hardscapes into welcoming rest points where people can mingle, freely and safely.

Craig Hamburg shares many of their sensibilities. “I’m bummed that housing is so often treated strictly as a commodity,” he said. “I go to conferences with panels repeating buzzwords and saying things like ‘This is the hot thing for millennials’ – as if context didn’t matter.”

400 Grove Street in San Francisco, floor plan. The protrusions help introduce more light, as well as adding visual interest from within and without. DDG and Fougeron Architecture.

Context

Context is the art of fitting a new building in amongst its neighbors, in a way that creates something new and exciting, but isn’t completely jarring or out of place. A well-designed building that’s on a smaller scale can raise the bar for other new developments, challenging the next builder to create something equally attractive.

12 Warren Street in New York City, another project from DDG, directly references the context of New York State, intentionally replicating the feel of a stone outcrop, underscoring the horizontality of layered slate with additional sculptural elements in the lobby ceiling.

Space Efficiency and Cost Containment

Even the best intentions can’t eclipse the fact that real estate is getting more and more expensive in urban cores. More people want to live in the same space, and they’ll either get priced out, or have to make do with less. One way to make smaller floor plans bearable is placing greater emphasis on good design.

In a typical tract-home developer scenario, a common practice is maxing out the number of bedrooms in a single home, and cramming the maximum number of homes onto the same amount of land. The houses also seem to get bigger, but they don’t feel bigger. The developments seem barren, the detailing cheap. Whatever natural environment was there is simply razed. Even the undersized eaves provide no shade or relief from the glaring California summer sun.

However, even tiny footprints can feel spacious and comforting if the space is well-thought-out rather than formulaic. Hamburg says, “Financially, it has to make sense. Things get smaller because pricing is going up. The challenge is how to make a one-bedroom work with a smaller footprint. With developers, pro-formas dictate plans on a spreadsheet, but what residents really care about is their monthly rent.”

8 Octavia Street in San Francisco includes operable external louvers so that every apartment has full control over light at different times of day. Exterior shades are far more efficient than interior ones in controlling solar heat gain, because they prevent the glass windows from heating up. DDG, Stanley Saitowitz | Natoma Architecture.

Vertically Integrated

DDG develops condominium and apartment properties, providing design as well as construction, and then manages the buildings after the condos are sold. “We want to ensure that the buildings are well-maintained. We wanted to create a white-glove experience. We want to control it, not hand it over to a third party.”

Good property managers are hard to come by, and turnover is high. Hamburg explains, “A good property manager is entrepreneurial, can-do, and smart. Often what happens is one individual who’s a good property manager gets put in charge of other properties as well, and suddenly they’re stretched too thin.”

As a vertically integrated company, DDG maintains a level of oversight from design through construction of its projects. Left: close-up of a carefully detailed stone for 12 Warren St in New York City. Right, the stone facade being assembled prior to shipping.

Good Developers Are Not Speculators

DDG must feel outnumbered in a city where everyone loves to hate anyone who builds or even rents property. How does Hamburg feel about the phrase “greedy developers”?

“I hate it. Speculators get lumped in with developers, but developers are in it for the long term. A speculator will buy a building and TIC it [turn it into condos], perhaps use the Ellis Act or other strategies to evict the existing tenants, and then quickly renovate and resell the units.” Hamburg went on to clarify how a developer differs from other property roles. “Landlords aren’t developers. Speculators aren’t developers. Both are taking something that someone else built, and sometimes taking advantage of market cycles.”

345meatpacking, a New York City housing project from DDG, draws from the context of the Gansevoort Market Historic District, and has won multiple design awards. The amoeba-shaped openings in the awning are only one detail that have made this building a designers’ landmark in downtown Manhattan.

How Much Profit is Acceptable?

“Profit should not be part of the conversation. No one cares if developers lose money, except for the investors!” responded Hamburg. “When you go out to dinner, do you care how much profit the restaurant makes, as long as you have a good time and the price works for you?”

Hamburg pointed out a tiered divide in the restaurant business that also applies to real estate. “In restaurant’s it’s either a quick and easy meal, or a white-tablecloth experience. There’s a missing middle.” This missing middle in real estate would be the middle class, who can’t afford market-rate housing, but can’t qualify for subsidies or affordable-housing options.

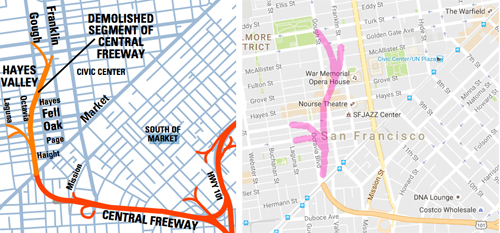

The Role of Hayes Valley Neighborhood Association

We discussed the Hayes Valley Neighborhood Association, and how we could get other associations to be more forward-looking and less insular. Hamburg pointed to the HVNA’s origins following the Loma Prieta earthquake of ’89. Prior to that, the Central Freeway had bisected the Hayes-Octavia neighborhood, making it a lot less livable than it is today.

Craig Hamburg has lived in San Francisco since 2005. He has been an HVNA board member since 2012, and currently serves as Vice President of the HVNA board. Hamburg is also on the Urban Land Institute’s Local Residential Product Council, and is a former Young Leader Steering Committee member with the United Way.

Landscaping is an integral part of good design. Too often, a bloated building will try to max out interior square footage and lose all connection with the outdoors. 400 Grove Street, San Francisco. DDG and Fougeron Architecture. Landscaping: Marta Fry Landscape Associates.

“Patricia Walkup and Robin Levitt were the two key people who organized the neighborhood. After the ’89 quake, the thinking was ‘We’ll just repair the freeway.’ Back then, the neighborhood was gritty and tough. Suburbanites would come in via the freeway to score drugs and prostitutes, and then leave. Part of the area was considered the Western Addition, and there was a lot of drugs, a lot of gang activity.”

Several San Francisco freeways were damaged in the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. The Central Freeway bisected Hayes Valley. Left shows the old freeway, right shows a current map of San Francsico, with an overlay where the Central Freeway used to be.

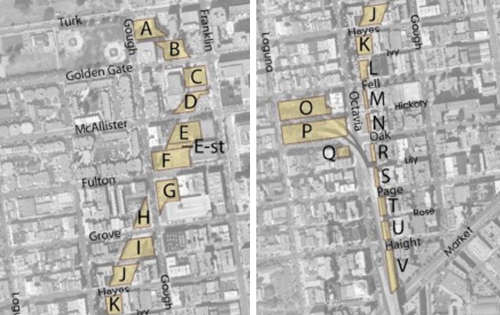

Then, activists in the neighborhood banded together to bring down the freeway and stitch the neighborhood back together. “People said, ‘Let’s clean up the neighborhood.’ That’s the origin of the Market-Octavia Plan. It was an opportunity to embrace new housing. The freeway’s removal freed up 22 parcels of land. That’s enough for roughly 1,000 new housing units, with 50% of those being affordable-housing units. The cool thing that the neighborhood and the City did that defused a lot of potential conflict was to dedicate half those units to affordable housing.”

Hamburg mentioned an interesting temporary use of Parcels K and L.”PROXY is a wonderful example of temporary use on parcels K and L, and is worth mentioning.” According to Envelope A+D, PROXY is a temporary open-space for “thoughtful experimentation”, including events, shops, and a walk-in theater.

Of the 22 land parcels freed up by the Central Freeway’s removal, roughly 16 are in some stage of development or completed. Lots are numbered A-V.

“The HVNA also encouraged market-rate developers to include affordable housing units onsite within their projects, rather than simply paying into the City’s affordable housing fund,” Hamburg went on. They didn’t want to lose affordable units to another area of the city. “Although, as it turns out, creating new affordable housing in another area, such as the Tenderloin, isn’t such a bad thing, as long as new housing gets built.”

“Another policy change that took place at that time, with neighborhood support, was a reduction in parking requirements. The Market-Octavia Plan required only 50% of the new housing units to have parking. Typically, in 2001, market-rate condos would have 100% deeded parking. Investors and lenders didn’t want to back condos without off-street parking.” This was all before the era of Zipcar, ridesharing, and other innovations. Now, that’s changing. “In DDG’s next two projects, there will be zero dedicated parking. Instead, we anticipate that residents can rely on public transportation, bikes, or other modes of transit.”

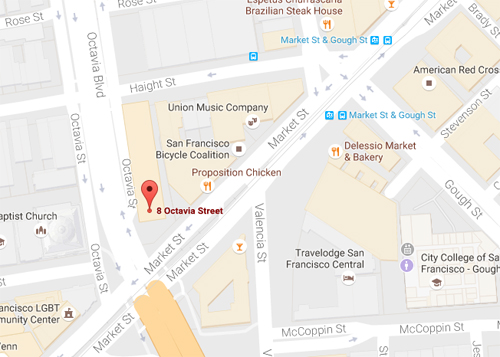

The 8 Octavia project sits at the corner of Haight Street and Octavia Boulevard in San Francisco – right where the demolished Central Freeway used to be. DDG and Stanley Saitowitz | Natoma Architecture.

Community Process

Did Hamburg have any advice on dealing with chronic obstructionism? “Listen. Just listen. For many people, change is hard. They want to be heard. Reach out to them early on.”

Just Say “No” to Bloated Buildings

“At the HVNA, they want to see good design. The Board has a mix of designers, merchants, academics, nonprofits, and people who work down at City Hall… people who care, and who have rational heads. Designs should be impactful, not relying on cheap materials simply trying to max out the square footage with floor space, without any attention to landscaping or integration with the surroundings.”

After the Central Freeway came down, Octavia Street in San Francisco was transformed into a boulevard, with open green space and walkable streets as part of the Market-Octavia Plan. The 8 Octavia project was built on land that was freed up from the demolished freeway.

8 Octavia

Our conversation centered a lot on 8 Octavia, a condominium building designed by San Francisco architect Stanley Saitowitz, with landscape architectur by Marta Fry. “Stanley has done other great buildings too, such as the Yerba Buena Lofts. The 8 Octavia project was a real challenge due to the space constraints. The lot was 40 feet wide and 265 feet long, with a downward slope of 20 feet from Haight to Market. It was hard to make a 50-unit mixed-use project with efficient use of space.”

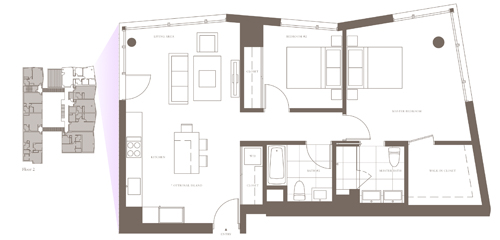

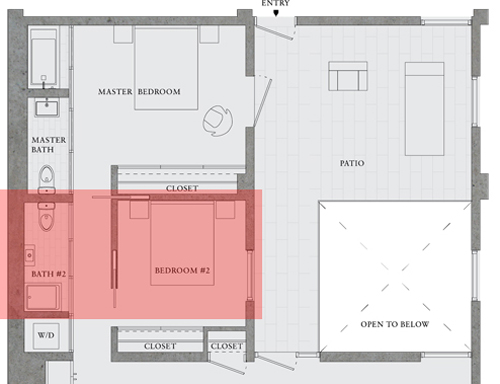

Sample floor plan from the 8 Octavia housing project by DDG with Stanley Saitowitz | Natoma Architecture. The bathrooms employ ingenious space-saving design techniques.

The market timing aided the project as well. “That project was started during the recession, and might not be workable today. It might be too expensive now. Some essential details, such as the louvers, were expensive and might have been eliminated.”

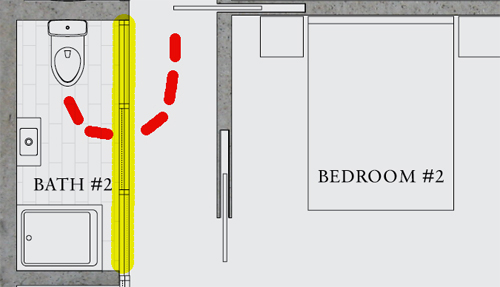

At 8 Octavia, architect Stanley Saitowitz and DDG maximized living space through the use of sliding glass bathroom doors that allowed hallway circulation to fulfill ADA requirements for wheelchair clearance. This approach allowed the remainder of the apartment to feel more spacious, while remaining fully accessible.

The Stanley Saitowitz project was ahead of its time in many ways, particularly regarding interior space efficiencies. For example, some of the bathrooms are linear, only 4 feet wide, with sliding doors made from frosted glass. Traditional bathrooms have ADA space requirements allowing for wheelchair turnarounds and with minimum clearances for toilets and sinks. In these floor plans, the corridor doubles as ADA space when the sliding glass doors are open. The space normally consumed by a traditional bathroom is now dedicated to living rooms or bedrooms, where people spend more of their time.

Hallway view of 8 Octavia, showing the bathrooms’ space-saving doors made from frosted glass. DDG and Stanley Saitowitz | Natoma Architecture.

“Not everyone liked the Saitowitz designs. It was polarizing. Some buyers didn’t like it at all, while others loved it.”

Micro-Housing and Downsizing

One of DDG’s upcoming projects is actually micro-housing, with 300-350 square foot units. “The design challenge is making them livable, and how to make the small spaces feel bigger. What features should we include? Should there be built-ins, or customizations?”

Apparently, Stanley Saitowitz’ response to micro-housing doubters is, “Have less stuff.” Although this seems daunting at first, consider how much “stuff” actually goes unused. In denser urban environments, people tend to do more activities in common areas: libraries, gyms, parks. Do you really need a home theater when a movie house is around the corner?

How many condos have a gym with a custom-built stone arch inside them? This is from the DDG project at 12 Warren Street in New York City.

“A lot of gated communities feel empty. I like living in Hayes Valley because I know so many people. I know the people in my building, at the corner store. We ask about each others’ families. It’s about the people you know. And, cities can grow and change, too.”

The Path Forward

After hearing all this talk on the housing panel, everyone making so much sense and yet things are still taking 5 years to get through Planning, I wanted to know how we could hammer on a few toes.

“Legislation, particularly CEQA reform, and density bonuses,” responded Hamburg. CEQA refers to the Environmental Quality requirements that, in San Francisco, have been abused by a few players who basically want NO building, NO new housing, and NO change… they’ve got theirs, and the job-seekers be damned.

400 Grove Street has a lot of life and interactivity on the first floor to engage with the public as well as the apartment residents. DDG and Fougeron Architecture.

“We have 101 municipalities that don’t talk. They all want to attract jobs and tech companies, but none of them want to allow new housing. And, public transit is not unified.” AIA Housing panelist Sonja Trauss had pointed this out as well, noting how other major metropolitan areas such as New York City had unified long ago.

Regarding the growing concern with homelessness, “We have a City of 900,000 people and as many as 10,000 of them are homeless. Jail and citations are not the answer. Neither are tent cities under freeways. It’s not safe, and the duress of living on the streets only intensifies people’s problems.” (It could be added that shelters aren’t a permanent solution, and that many people, especially women, often regard shelters as unsafe.)

41 Bond Street is another example of housing design that references local context, in this case New York City. By DDG.

This ties back to Sonja Trauss’ emphasis on building more housing of any kind, all kinds – and David Baker has proven that it is possible to re-house even seriously distressed populations: homeless seniors, people with mental health issues, and serve them with thoughtfully designed housing that is both supportive and cost-effective.

Vision

So, what should the City focus on, or the greater Bay Area? “Focus on CEQA reform, public transportation, and building height. Have great public transportation with higher density around the transit hubs – maybe 30 stories, even 50 stories. Get more cars off the road.”

41 Bond Street in New York, like the other offerings from DDG, includes carefully landscaped plantings and a rooftop garden.

We touched upon a new housing project by David Baker Architects at 1950 Mission Street. Despite being the first 100% affordable housing to be developed in San Francisco in a decade, it has garnered objections from people who think it’s too tall, even though it’s under 10 stories.

“San Francisco has an aversion to anything over four stories tall. There’s no reason for this. That housing project in the Mission is needlessly controversial. It’s replacing a Walgreen’s and a Burger King! Done correctly, the project is an opportunity to provide both market-rate and affordable housing right next to a BART station. With proper context, this would be a win-win.”

Within the Planning Department, Hamburg had a few ideas as well. “Have individual planners focus more on the same types of projects. Right now one planner may evaluate a proposal for a large multi-family housing project, and then work on approvals for a single cell-phone tower.”

“We need more neighborhood master plans like Market-Octavia.”