Why is Art Better than Tech?

by Rebecca Firestone with Mark English AIA | Interviews

Could art help people to act as “disruptive innovators” and “agents of change” in a different kind of way? Gary Hutton: “Any fool with enough money can buy a Ferrari.”

(Photo: Matthew Millman)

This article is part 2 of a series. Read Part 1 here.

Why Is Art Better than Tech?

It seems a shame that the Bay Area is so awash in talent and discretionary income, and yet all these super-intelligent software engineers don’t seem to spend any time on anything outside of technology problem-solving, or raising investor funding. Maybe it’s the relentless focus on STEM education in schools. Could art help people to become “agents of change” in a different kind of way? I asked Gary Hutton, interior designer for serious art collectors, for a convincing argument.

“Art is more universal. Building the next great widget is a laudable task. It propels our society. But art speaks to the soul rather than the pocketbook.”

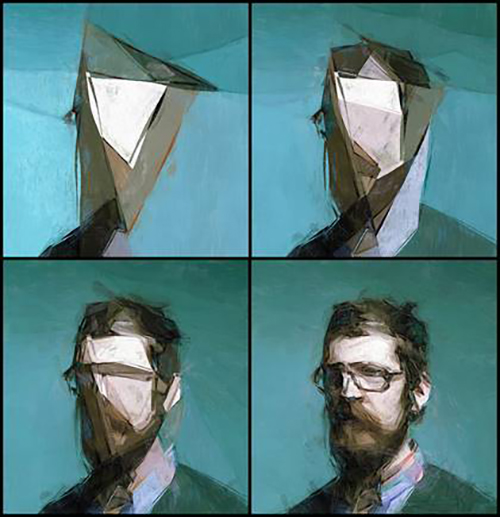

At some points, a union of art and technology transcends this false dichotomy. The works become artful, exciting, dangerous. Dorkbot and Odd Salon are two places where you can see a crossover between art and science, often in strangely entertaining ways. Steve DiPaola’s expressionist art simulator was frighteningly good…

Professor Steve DiPaola presented at a recent Dorkbot salon on January 31, 2018 on sensing and simulating facial expressions, and even simulating distinctive art styles.

Become a Thought Leader

Silicon Valley business leaders are focused “shareholder value”, and “investor returns”, while knowledge workers are concerned with “metrics” and improving their skillsets to stay competitive. What could possibly be in it for them to invest in something immeasurable like art? Well, for one thing, being an art maven can make an ambitious young entrepreneur stand out from the throng. It’s about having that consummate skill – a skill that nobody else has.

- Schreyer intentionally placed in this corner of her living room in LA to catch the afternoon sunlight. Interior design by Gary Hutton. “Architect Joe McRitchie was awesome to work with.” Photo: Matthew Millman

- Schreyer’s LA living room from the other side shows “A Thousand Daddies” by Mark Bradford with the Donald Judd off to the right. Interior design by Gary Hutton. Photo: Matthew Millman

Gary Hutton: “Any fool with enough money can buy a Ferrari.”

“Never Buy Art as an Investment”

Like the Vogels, Schreyer has turned down many astronomical offers for selected pieces. For every piece that appreciates, though, 5 others have dropped in value. She’s even said, “Never buy art as an investment.”

Schreyer’s San Francisco apartment focuses heavily on text-based art such as Ed Ruscha’s “Etc”. Interior design by Gary Hutton. Photo: Matthew Millman

- Gary Hutton’s interior design showcasing works by Lawrence Weiner and Larry Bell, among others. Piece to the right is a planar section created with a single piece of string, with the shadow then painted on the floor an wall. Interior design by Gary Hutton. Photo: Matthew Millman

- Close-up of Lawrence Weiner’s “A Cloth of Cotton Folded One Way to Obscure Folded Another Way to Enhance”. Photo: Matthew Millman

- Ed Ruscha’s “Etc” co-existing with other artworks in this interior design by Gary Hutton. Photo: Matthew Millman

Hutton’s advice seems like common sense once he says it. “Don’t be a fool and throw your money away. Educate yourself. Buy what you love, something that thrills you every time you see it. Something that makes you happy to be alive.”

Schreyer is also concerned that contemporary art has become so expensive, that it’s more or less an exclusive club. It’s one reason she works so hard on museum boards to make art accessible to the public. “Much of her legacy is promised to museums.”

Cross-Cultural Art Forms

What about art from other cultures? I wondered. How can one ethically go about collecting artifacts or art from another part of the world, particularly with the existence of a large economic disparity? How do you know it’s not “cultural appropriation”, or is that even a valid question? Gary Hutton had a very interesting take on this.

“Every culture has an art form. It can be very specialized, and not obvious to outsiders.” Just like Modern Conceptual art, in fact. Hutton mentioned that there was a certain African people who’d made an art form out of critiquing the markings of cattle. Really? I wondered, and tried searching for this online. I did find some amazing images of traditional Nguni cattle breeds, with markings that looked like exquisite watercolor paintings. And of course… you can buy the hides online.

The entryway to Schreyer’s LA home. The “leaves” on the steps are not leaves. They are aluminum, covered in fabric collected from refugee children around the world, by artist Pae White. Photo: Matthew Millman

- Pae White’s leaf artwork, closer up. The aluminum leaves are to be scattered anywhere, like refugees scattered to the winds. Photo: Matthew Millman

- Artworks by Ruth Asawa, Richart Artschwager, Andy Warhol, and others. Interior design by Gary Hutton. Photo: Matthew Millman

- Artworks by Ruth Asawa, Lee Bontecou, and Robert Morris. Interior design by Gary Hutton. Photo: Matthew Millman

Hutton cited art philosopher Denis Dutton, who had an essay on Tribal Art explaining this. Turns out he was talking about the Dinka people of east Africa, who are so interested in cattle aesthetics. (The Dinka-bred cattle markings don’t seem quite as varied, but their horns are amazing.) Denis Dutton’s standard for “what constitutes art” among indigenous people is worth quoting in full. It should sound familiar.

“The characteristics of the art of tribal societies have been catalogued by H. Gene Blocker. According to him the tribal art object normally [ has the following characteristics ]:

(1) is of aesthetic (sensual or imaginative) interest,

(2) is made by a specialist producer of art,

(3) is subject to critical appraisal,

(4) is set apart from ordinary life,

(5) represents the real or a mythological world or events in either literally or symbolically,

(6) is intended to be understood as a symbolic or as mimetic representation,

(7) involves the possibility of novelty within a tradition,

(8) is made by a person often seen as “eccentric” or socially alienated within the indigenous context.”

(Above quote slightly re-formatted for easier reading)

Attributing artworks can vary among ethnic groups as well. In a small, closed, traditional society, works may be unsigned, but as Hutton explains, “Everyone in the community knows who made each piece. People know makers from the past, too. It’s preserved as oral history.”

Collections Have Souls, Too

The strength of a collection is as much in the interaction among the artworks as it is in the individual pieces themselves. “There’s a house I recall, a very well-known fashion designer, where it’s clear that they were buying from a checklist of named artists.” By contrast, when the stylist for the book came out to Schreyer’s LA house, she stood in the entryway and said, “Wow. This woman really knows her stuff.”

The outdoor courtyard blurs the distinction between “design” and “fine art”. Gallery pieces are framed by design elements by Gary Hutton and Hiram Banks. Photo: Matthew Millman

Strategies for Art Collectors

In addition to a strategy, one needs a methodology. For example, Herb and Dorothy Vogel had 3 rules: affordable, carry-able, could fit into their apartment. They dedicated one salary to living expenses, and the other to acquisitions. They practiced total cultural immersion, spending all their free time at shows and visiting artist studios.

Another of Gary Hutton’s design clients is a couple who’d split up at shows and then re-convene later to compare notes. Another client only collects photography about gay issues. “Nothing erotic, more about themes of otherness, outside-ness.” Other collectors may work to create a snapshot of an entire historical period.

Chara Schreyer’s mission statement? “Artists who have changed the course of history.”

Christopher Wool, “Untitled”. Schreyer had to promise to donate it to a museum in order to be allowed to buy it as a private individual. Gary Hutton designed and built the table. Photo: Matthew Millman

Corporate Collections

Sometimes, it’s the corporate collectors that drive the prices of art so high. How are they different from private collectors? “Corporate collections use art consultants.” Do THEY care about the art? I wondered.

Hutton cited the founder of Rosenberg Capital Management, who ran a world-class financial services company. “He really knew his stuff, and collected great contemporary art for his office and the offices of his managers, because that’s what he wanted to see when he went to work every day.”

Frank Stella’s “Honduras Lottery” anchors the living room of Schreyer’s home in Marin. Interior design by Gary Hutton. Photo: Matthew Millman

Designing for Art Collectors

Gary Hutton has designed many interiors for art-collecting clients. A passion for the art is the primary qualifier for Hutton in whether he’s interested in working with the person as a design client. “I’m looking for clients who have a deep emotional connection to the work. Their art speaks to them in some way. It’s not just a status symbol for them.”

“The environment should present the piece in its best light. I don’t have to see all the pieces in person, but I do want to see photos. The background and spaces should be flexible, to accommodate different pieces, because people may rotate them.”

Gary Hutton designed this master bedroom with Eva Hesse’s “Top Spot” above a white marble fireplace. Photo: Matthew Millman

Many of Hutton’s projects include collaborations with San Francisco lighting designer Hiram Banks, whom we’ve featured in the past. Hutton also mentioned architect Joe McRitchie, saying “He was awesome to work with.”

“It’s good to have pieces that really speak to each other,” said Hutton. “I don’t select art for my design clients, but I will sometimes send them to places where I think they might find pieces that appeal to them.” Many dealers will loan out artworks, like Oriental rugs, so that potential buyers can see how they work out in the space.

“I choose colors and materials with care. It’s not just another ‘beige room’. The art is the main provocateur, but if you take the art out, the interior is still interesting.” A carefully crafted Minimalist art piece may have subtle colorations, textures, and hand finishing. One could approach Hutton’s interiors as a Minimalist environment, which can then contain other artworks within it.

Working With Architects

Hutton has collaborated with a number of architects, including Aidlin Darling, McCritichie Design, Tim Gemmill, Mark English, Jerome Buttrick, and Jim Jennings. Many of his projects mention Hiram Banks for lighting design, and William Peters for landscape design. A great interior adds perfect style to a great building, and makes it “home”.

So, what do you want to get out of this article? I asked. This was after taking up 3 hours of his time. “Exposure to the architect world. I want to meet more architects.” And architects might want to meet him, too.