Olle Lundberg: Hand of a Craftsman, Part 1

by Rebecca Firestone with Mark English AIA | Interviews

“Our firm’s work is really about small projects, carefully crafted. It expresses the hand of the builder. The role of the craftsman is so rare today. You can take something hand-crafted and replicate it by machine, but then it’s no longer craft.

I prefer materials with depth and heft, with an elemental power about them. The power comes from the natural piece that they came from, or from the way the material was created. Our palette is nature-oriented. Even steel, I consider a natural material, because it comes out of the earth.

A wave of stage fright passed through me as I walked up to the door of Lundberg Design on San Francisco Third Street Corridor, a somewhat renovated industrial-chic area near the waterfronts of Mission Bay and bordering San Francisco’s historic Dogpatch neighborhood. * At least this must really be the place, I thought. It’s got a handmade door that looks like an airlock.

* Historic to the neighborhood association, that is.

The conversation below mostly took place between Olle Lundberg and Rebecca Firestone, with additional remarks from Mark English.

What was it like for you growing up? What did you do for fun as a kid?

My parents immigrated from Sweden. I was born two weeks after their arrival. My father worked for Procter & Gamble as a chemical engineer, and moved into managing paper mills. We tended to move a lot, so I went to a different school every year until high school, when I was sent to boarding school in Connecticut.

I thought only military families moved that much.

It makes you self-sufficient. I was a happy kid nonetheless. Living in lot of different houses, I was exposed to different floor plans and spaces all the time. One house I remember was in Sheboygan, Michigan. It’s a mill town in the Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, off Lake Michigan. There’s nothing there now. It’s a place the world has forgotten.

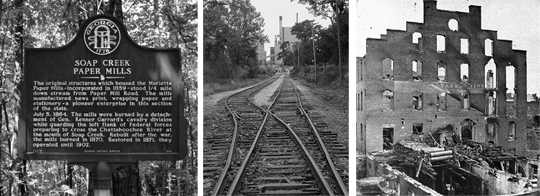

These three mills, one in Georgia, one in Michigan, and one in Richmond, all show examples of America's paper industry.

But it used to be the center of the lumber industry, and this house was built by a lumber baron as a re-creation of a Georgian governor’s mansion. A bizarre notion, perhaps, but it was an amazing house. It was three stories. Every room had its own porch, and it had solid marble bathtubs. Procter & Gamble was about to tear it down to build a parking lot, but our family got to live in it for a year before they eventually did destroy it.

Because we moved so much, our homes were never seen as overly precious. My parents gave me free rein to build things in them. When I was 12, I made an outdoor counter-weighted elevator, a dumbwaiter.

And then you went off to boarding school in Connecticut.

It was a new experience. It was an odd fit for me because most of the other students were from wealthy East Coast backgrounds. It left me feeling a bit of an outsider. Academically it was very good, and I also did a lot of athletics. Even though I got a good education, I was still a small-town boy at heart, and I wanted to go to a small college. I didn’t know at all what I wanted to study. I went to Washington Lee University in Lexington, Virginia, and majored in English literature.

What were your favorite literary works at that time?

I focused on the Southern contemporary novel. William Faulkner was of course the foremost author in that genre, but my personal favorites were Eudora Welty and Flannery O’Connor. I finished my major early, in the middle of my junior year, and I still needed more coursework to graduate, so I went into sculpture.

Tell me about your sculpture experiences.

It was an interesting fine-art program. The professor was just a kid, from New Orleans. I don’t even remember his name now. But he was very inventive, very hands-on. He would figure out how to build stuff, like kilns. We did glass casting, metal casting, forging. The program was great from a technical point of view, because I learned how to weld and cast. And that was how I got my start as a fabricator later on, through this hands-on experience.

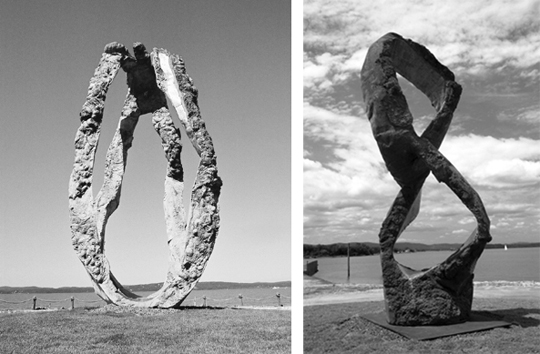

Olle Lundberg's brother Peter created these sculptures. Left shows "Dancing With Torsten" and right shows "Figure Eight".

I don’t really have much to say about my own sculpture as an undergraduate. My brother Peter is really the sculptor now. He is the master. I am nowhere near him when it comes to sculpture.

[Note: Peter Lundberg’s works mostly seem to be named after mythological gods and goddesses from Norse and other pantheons – another form of heroic monumentality. For example, Utlunta is a Cherokee goddess of physical prowess, and “Torsten” could be translated as “Thor’s hammer”.]

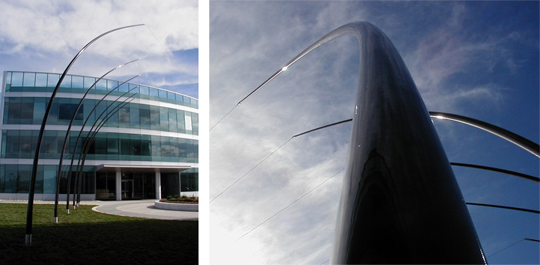

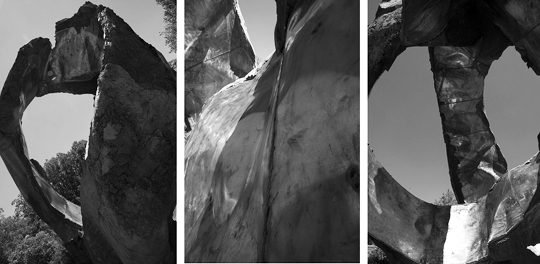

Although Olle Lundberg claims not to be a sculptor, his outdoor installation "Carbon Arcs" is conceptually and aesthetically powerful enough to argue otherwise. Photo: Courtesy Lundberg Design.

So how did you end up going into architecture?

Washington Lee only had dorms for freshman students, so after my first year I had to live off-campus. I found an old chapel just outside of Lexington and convinced my dad to let me buy it for $10,000, with a friend of mine as a partner. We fixed it up and leased out three rooms to other friends of ours to pay the mortgage.

One unforeseen bonus of this was that it paid for my grad school, since the building was worth more when we sold it. I suppose that’s how developers always think, but I think a lot of successful development efforts are really about timing, not the product.

But I still didn’t know what I wanted to do. A degree in English literature wasn’t going to lead to any paying jobs all by itself. Now that I was a state resident, I could get in-state tuition rates to the University of Virginia. I actually applied to several grad schools: business, law, and architecture.

Well, I was wait-listed at Stanford Business School, but I got into both Yale and the University of Virginia for architecture. Yale tuition was $25,000 a year, but the U-VA tuition for in-state residents was only $5,000. Since I was paying for it, it was a clear choice to stay with U-VA.

Yale would have been a bad choice for me anyhow. You really need prior experience in architecture to succeed there. They have you work with real star architects, too. Many grad schools have a very singular focus, and you have to already know what you want. But University of Virginia is good for people who are still searching for their eye, people who haven’t figured it all out yet. The University of Virginia had talented faculty and was good at promoting different ideas, rather than promoting one vision. It was a very creative place.

Then what?

After I graduated, I worked in Charlottesville, VA, for a former professor of mine, Bob Vickery, at his firm VMDO Architects. Then I met Bob Marquis, who offered me a job in San Francisco. I worked for Bob for four years from 1980-84. That firm later became SMWM, which has since been bought again by Perkins & Will.

This was at the peak of their productivity. At that time, they were doing projects like the Stanford Music Building, but I did the houses, because no one else at that firm even knew how to do houses. Every so often a faculty or administrator would want a house, and that work fell to me.

Huh? I understand they mostly did institutional work, but don’t they LIVE in houses? How can an architect not know how to design a house?

Actually, everything from the packaging to the way you manage a project is totally different. Getting back to the story, I then designed a house for my sister. Like any really good first project, it came in at twice the budget! So I decided to build it myself to save on costs. It took two years.

Aha, so you DO know construction. I was wondering about that, because you do so much fabrication but you don’t do design-build.

I think that with design-build, there’s always an inherent appearance of conflict of interest. Even if the designer is scrupulously honest, the client may not see it that way. The building portion of a project is a rather tense period, because you are spending a lot of the client’s money. People are very scared when they’re spending that much money. Trying to convince someone who’s already nervous that you’re really on their side is a lot harder when you’re also the builder, and these cost issues come up.

That’s why for our fabrications, we are very clear about what we will charge, and we actively invite the client to price it out at other fabrication shops, just for their own peace of mind. Since our shop is already used to our own work, we usually come out lower anyway. But we don’t make a ton of money doing this, and the client needs to understand this and trust us.

Even if you don’t do construction now, doesn’t your prior hands-on building experience give you more credibility as an architect?

There’s one school of thought that too much standard construction experience limits your imagination, but I think that knowing how things are built increases one’s own vocabulary. We’re always looking at different industries, like aerospace, to see what new industrial building techniques we can employ.

Assembly details from three projects by Lundberg Design. Top left photo: Elena Dorfman. Top right photo: Richard Barnes. Lower photo: Ryan Hughes

Owners may have heard horror stories about un-buildable buildings. Our shop is a marketing tool that helps us to convince them that we know how stuff goes together. The shop also helps us to solve problems that come up.

These residential project details fabricated by Lundberg Design are not overbuilt, but they're clearly strong enough to withstand even the most high-impact lifestyles. Left photos: Ryan Hughes. Right photo: Elena Dorfman.

Our shop is mostly metal fabrication. We outsource the glass and most of the woodwork to other places. Wood and metal aren’t that compatible in the same shop, anyway. The oils and sawdust from the wood aren’t good for the metalworking machinery. We don’t do other people’s stuff, though. Only our own.

Olle Lundberg uses the light-diffraction qualities of glass in ways that show the thinking of a sculptor. Left photo: Art Grey. Right photo: Cesar Rubio.

Most housing contractors are wood guys. Steel shops want repetitive work because it’s a money-maker. But we really don’t want to do repetitive production, because we enjoy the hand-crafted aspect, the uniqueness of our pieces. So yes, having construction experience is helpful. In our shop, not everyone walks in here knowing it, but we do a lot of mentoring and if the person is talented, they can pick it up.

Lundberg Design fabricated much of the interior for the Hotel Diva project, including the sculptural steel wall shown in this photo. Photo: Courtesy Lundberg Design.

I like building things. It’s a form of therapy. Our cabin project is like that. It’s an ongoing process, which is more fun than actual completion.

Who & what are your influences?

Japanese Buddhist gardens, and the gardens more than the architecture. There’s something about the relationship of the hardscape to the plantings. It can be hard for a landscape architect to work with us, because we find it hard to relinquish control over the hardscape, which leaves them with nothing but plant selection. Our buildings are tied to the land.

Peter Zumthor’s work. I’ve visited some of his works. Therme Vals [baths] is his most poetic building, and actually has many similarities to Falling Water.

Richard Serra. Spatially, he achieves a simplicity in his sculpture that is hard to describe. Gehry’s work is a bit like it, but Gehry is more complicated.

Olle Lundberg admires sculptor Richard Serra's work for its spatial simplicity. Serra uses a lot of Cor-Ten steel, which gives his works a monumental yet also tactile quality, and rusts into a rich reddish brown.

Mark di Suvero. My brother Peter is also a sculptor, and worked in di Suvero’s studio for 10 years. I loved di Suvero’s process. He goes into his studio with a crane and starts messing around with steel! Also, he makes his own stuff, which Richard Serra does not. Anthony Caro is another one.

Olle Lundberg's brother Peter worked for Mark di Suvero for many years. Shown here is di Suvero's work "Intersection".

Andy Goldsworthy’s work I like for its relation to the site. I’m most interested in his earthworks, and his more permanent installations.

Olle Lundberg likes Andy Goldsworthy's sculptures, particularly permanent installations such as this work, titled "Three Cairns". Also see "The Wall that Went for a Walk".

Another influence came from the mill towns where I grew up. The paper mills there are larger than life. They’re on a heroic scale.

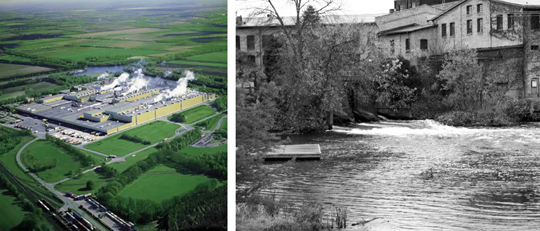

This modern paper mill still shows the same heroic scale as the older paper factories in Michigan, where Olle Lundberg grew up.

And they’re half in the water… clean water comes in, polluted water goes out <laughs>. I was fascinated by that marriage of the building with its surroundings. I remember one mill in Green Bay that had a giant island piled with sulfur right in the middle of the river, for storage, sulfur being used in the paper-milling process. It was a huge bright yellow pile. You can’t store it that way now, of course.

The scale shown in the modern paper mill on the left is emphasized by its surrounding landscape. The right shows a paper mill in New England, where the entire rear of the building runs right up to the water.

The door at the Hourglass Winery reminded me of the houses people used to build out of old bottles. Have you ever visited any folk-art environments like Bottle Village?

I haven’t been to those, but I do appreciate the childlike inspiration and elemental ideas in folk art. I have a couple of wood trucks that some guy carefully collaged. I think we’re all searching for those powerful, simple ideas.

It’s a process of editing. When you’re young, you want to include ALL your ideas in every piece. It can get fussy, fetishistic even. Too many details, or doing things just because you can. Our details are few but important. I used to love Scarpa, but now I find his work to be over-done with too much detail.

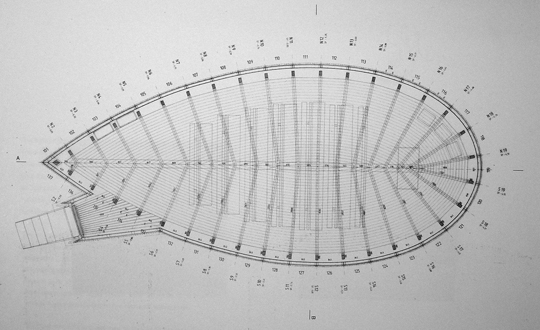

Zumthor’s work is quiet. I want my buildings to be quiet like that. He did this one chapel that’s shaped like an aspen leaf, with a floor that floats. The overall effect is like being in a boat, and the shape is organic but not perfectly symmetrical. In other projects, a floating floor might not be as central to the design, it might just be a clever idea. In Zumthor’s chapel, though, it’s perfect.

The floating floor in Peter Zumthor's Saint Benedict Chapel enhances the feeling of floatation, of being on a boat. Left photo by Terence Tourangeau (original color photo).

The Hourglass Winery project had a super-low budget. We talked them out of doing a building, instead we chose to cut into the hillside. The budget limitations drove that project.

For the Hourglass Winery, Olle Lundberg decided to cut a cave into the hillside. Photos: Ryan Hughes

What about details at different levels of scale? I sometimes find that having details at different scales is a lot better than a mess of details all at one level of zoom.

A lot of my buildings have large gestures. But you need to be comfortable on a human scale as well, and to address physical needs. You have to consider how the space needs to work. You can build things into your project that have human scale, which can actually co-exist within a large space.

In the Moss Room by Lundberg Design, human scale is achieved through careful attention to lighting, and by sculpting the space with ceiling articulations. Photos: Ryan Hughes

I approach form and composition in a sculptural way. My buildings have a monumental quality when first approached. Small details are important in that they show how well things are executed. It calls attention to the care with which the project is built. It expresses the hand of the builder, and ties humanity back to the art of building.

A staircase that promenades across the entry wall allows guests to fully experience the scale of the room through a gradual entry. Note that the wall at the Moss Room has since been re-planted. Photos: Ryan Hughes

The role of the craftsman is so rare today, but we can still express that. It’s the responsibility of the architect to express that. It’s the act of caring about building, like caring about cooking.

The sense of proportion in this detail from the Rudd Winery project by Lundberg Design is shown in the careful choice of the sizing of the mirrors and the spacing between them and the surrounding planes. Photo: Courtesy Lundberg Design

Our interview with Olle Lundberg is continued in Part 2.

Kelly Condon

03. Feb, 2010

This is fantastic.

It makes me want to make a collection of people’s life stories (how they got there) – without the part we already know (where they are).

So interesting to think about military families generating kids that have thought more about space & typographies because they had to.

Not that they all do – but I think we all had some a-ha moment that got us into all the different things we do.

Nancy McClure

30. Jul, 2010

Appreciate getting the ‘back story’ to some names I’d crossed paths with. Very nice biography, and nice that you included visuals of the influences/tangential sources.