Zack/deVito Architecture: Designers and Master Builders, Part 1

by Rebecca Firestone with Mark English AIA | Interviews

“I like to make things. You can do things structurally with metal that you can’t do with other building materials. Steel is strong, so you need less of it, less bulk, to create a structure. It’s about tinkering, and paring down… how slender can I make this piece of steel and still have it work? Working with stairs, the question is, can I make a particular structural element any smaller?” – Jim Zack

“When you become the client, you realize how hard it is to be a client. Working on our own homes has given me a lot more empathy for the role of the client. When you live in your own projects… you get a heightened understanding of where things should go, and how to accommodate the human body. In my own designs, I emphasize views and vistas, both of other parts of the house and of the outside. Each view is constantly referring to something else, but it’s also telling you where you are.” – Lise de Vito

“I can’t draw.” Jim Zack, a San Francisco architect whose firm, Zack/de Vito Architecture, has just won an AIA Merit Award, admitted this without a blink. “I develop the concepts, exploring them through computer drawing tools, and then have the details worked out by my designers on staff, based on my ideas.”

What’s this? An architect who can’t draw? What about all those lovingly crafted pen-and-ink portfolio pieces? Everyone knows that a master’s hand can only be discerned through revisions on trace paper, taped over the computer-generated drawing sheets. Isn’t that what being an architect is all about? It’s all about the design – as judged by images, not by walkthroughs – and a designer can be more famous for unbuilt projects than for built ones. It’s almost as if a building doesn’t really exist unless it comes with an architectural rendering, and a theory, even if it’s already built and in use.

Well… apparently the creative process is as unique as each creator, and conceptions of space can be communicated and developed in multiple ways: the traditional hand sketch, an AutoCAD file, a computer rendering, a physical model. So, how did Zack make such a success of himself, as an architect and as a design-builder?

Jim Zack and Lise de Vito of Zack/de Vito Architecture live in this award-winning home which they designed and built themselves.

Turns out Jim came to architecture in the old-school way – through field experience as a builder, only afterwards getting his architectural Bachelors and Masters degrees at UC-Berkeley. His wife and business partner Lise de Vito has a fine-art background and grew up in a household where both her parents were designers. The two met at an art opening. Later, Jim and Lise designed and built a series of homes for themselves and their growing family. The old-fashioned notion of architect as master builder suddenly takes on a new life and credibility.

Several voices are represented in the following discussions that took place at the offices of Zack/DeVito Architecture: An initial conversation with Jim Zack (JZ), Mark English (ME), and Rebecca Firestone (RF). A subsequent interview between Rebecca and Lise de Vito (LD) follows.

RF: Jim, could you tell us about your background?

JZ: In junior high I was “the shop guy” and it just never stopped. I liked working with metal and wood; I enjoyed tinkering and making things. Later on, UC-Berkeley had this amazing shop, and I was good at it – so I was still “the shop guy”.

I learned how to build long before I learned how to design. I was a carpenter for 6 or 7 years after high school. By age 23 I had already designed and built two homes with my dad, but I’ll never, ever tell anyone where they are. I had only taken some junior-college drafting classes.

JZ: The other thing that ties into this is motorcycle racing. I was very enthusiastic about motorcycle racing when I was a kid. Finally at around age 23 I realized that I was never going to be the national champion of motorcycle racing. Professional motorcycle racing ties back into making things. Those early racing bikes were all hand-crafted, hand-machined, and had to be tinkered with constantly. I can’t seem to get away from making things, although I’ve tried many times.

RF: Why would you want to stop making things?

JZ: I wanted to be a groovy, cool, designey architect, and not get my hands dirty.

RF: But now design-build is cool.

JZ: After school, I wanted to be self-employed. Then in the dot-com era, we stopped building but then we worked on a spec project which got us back into design-build.

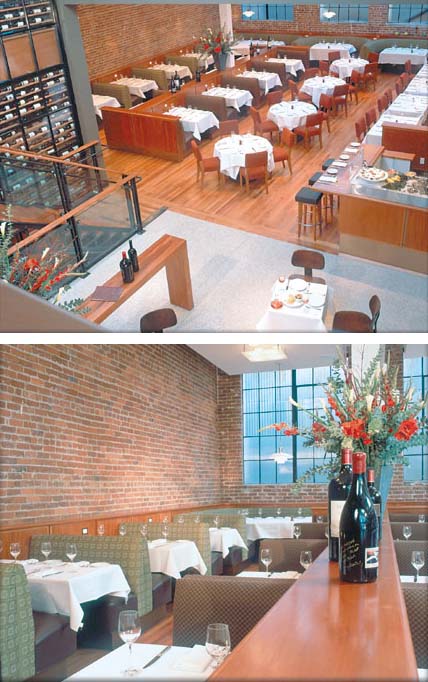

ME: How did your project with Gordon’s House of Fine Eats fit in?

JZ: It started when Gordon saw our Globe restaurant project. At the time, the Globe a tiny, unknown little place. Now they’re well-known. Gordon saw it and engaged with us right away, and we had a great relationship. Our firm built the cool fixtures and the pieces – so we got back into design-build through that.

Zack/de Vito Architecture's design for Gordon's House of Fine Eats won an SF-AIA Honor Award in 2001.

JZ: We like both, but I prefer residential design/build over restaurants. The pace is different. A house might take 14 months from start to finish, but restaurants are more temporal. They want it next week, because every day they’re not open, they’re losing money.

ME: Tell us about your materials. Why do you like steel and metal?

JZ: I like to make things. You can do things structurally with metal. Steel is strong, so you need less of it, less bulk, to create a structure. It’s about tinkering, and paring down… how slender can I make this piece of steel and still have it work? Working with stairs, the question is, can I make it any smaller?

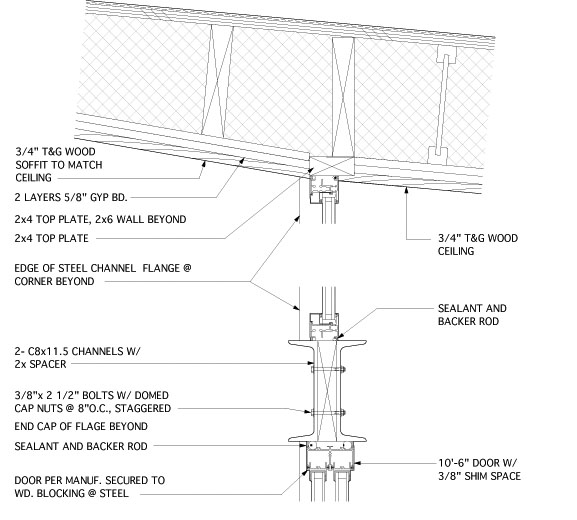

A high level of craftsmanship characterizes both wood and metal work in Zack/deVito's Bacar project.

JZ: After all those years in the shop, and then working as a builder, I have an intuitive sense of how much steel to use and what it can do. Architects with only theoretical training just don’t have as much of a sense of the material. They don’t know enough about how to detail it. Most architects would have those details done by their contractors as shop drawings.

JZ: One reason for my attraction to metal is its mechanical precision. You’re thinking in thousandths of an inch. I loved the exploded drawings in the mechanics’ magazines, the ones that show a motor blown up to show each individual part.

These aren't exactly of the same bike, but the point is that the cutaway drawings depict every component, and a detail drawing would show labels and measurements as well.

JZ: This goes back to my motorcycle racing days too. The old Motocross bikes were all hand-made – by someone with $1M to spend. Like a Ferrari. The professional riders all had custom factory models. Nowadays I think they require them to ride on the same bikes that are sold commercially.

JZ: This has parallels in architecture. Commercial buildings are assembled from pre-fabricated parts, whereas each residential design is unique, and the builder has to work it out as the work progresses.

RF: Tell us about your furniture. How do you come up with things like the steel chair or the I-beam table?

JZ: A lot of the time it’s just what I happen to have around, and thinking, “What can I make out of this stuff, given the machines available to me, and my own level of skill?”

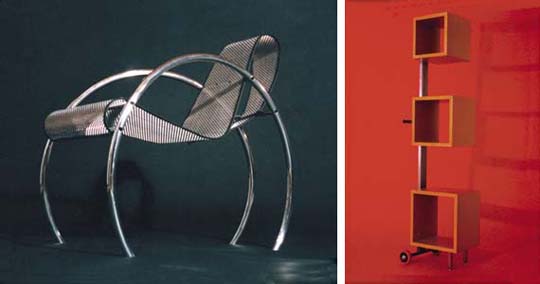

Jim Zack made the Spring Chair and the aluminum, glass, and cast concrete I-Beam Table just for fun.

JZ: The furniture I’ve done for restaurants is fairly standard, mostly utilitarian. Things like that aluminum chair were made from scraps I had around. Actually that chair is pretty comfortable. This I-beam table [at which we were sitting]… I was inspired by how some of our Bay Area bridges are put together. And maybe I just liked working with the aluminum, too.

The Hoop Chair and the Cubes rolling shelf are more examples of resourceful invention from Jim Zack.

ME: Well, you’re your own client for the stairs in your office.

JZ: In a more traditional client-architect relationship, there’s a leap of faith. The client has to pay, and hope that the end result is worth it. No one knows how it’ll come out because they’ve never done it before. Each new residential project is kind of its own proof of concept.

ME: Stairs are such a central component of a home.To me, they are the erogenous zone of the house, a place where it all comes together in a movement choreography.

JZ: Things happen on stairs, people meet and pass one another. It’s the interaction and flow of a home. A spare, minimalist design can create a feeling of openness. You can’t get such an open feeling from an all-wood stair, because you need to use more material. A metal stair can be part of the structural system of the home.

Elegantly made stairs, with a minimum of material, are a formal sculptural element fostering interaction between levels in these two projects from Zack/deVito Architecture.

ME: What’s your design-build method?

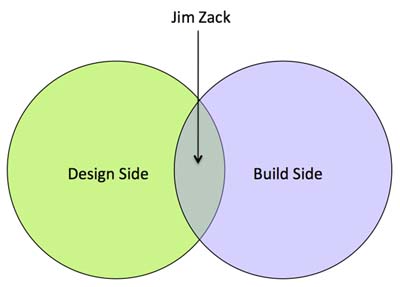

JZ: Well they’re two distinct businesses, really. On the architectural side, most of the designers stay in the office, and on the build side, most of the crew stays in the field. But, there’s a small overlap – that’s where I am, or possibly someone like a construction project manager. Someone who’s equally steeped in both worlds.

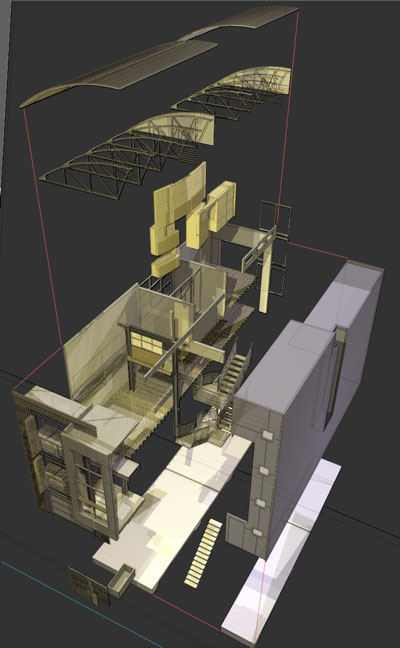

Zack's design/build business model keeps a distinct separation, but with a key person bridging the gap.

JZ: Actually the person in my office who’s the best at this is an intern! He just got out of school, so he’s a whiz at computer 3d modeling.

RF: How much overlap in skills is needed for the teams to function well together?

JZ: It doesn’t need to be 100%. Architects need to think more about building during design. It’s harder to train architects how to build than it is to teach construction crews how to deal with architects.

ME: The way things go together has to be internalized.

JZ: It also helps to have a good building crew. I pick smart guys – everyone on my construction crew is college-educated. One’s actually an architect, another’s a landscape architect. The architect came looking for a job, and we didn’t have any, but we needed a carpenter, and he had experience. So now he’s working as a carpenter and prefers that to working in an office.

Zack/deVito Architecture worked with several restauranteurs to create Tres Agaves, a modern Mexican restaurant.

ME: Do your architects know how to hand-draw? I’ve noticed that many architects coming out of school can’t even think in 3-D anymore.

JZ: That’s one reason I love the precision of the computer. Many of my designers make small 3-D sketches to investigate how things go together.

Computer-aided visualizations can show not just the facade, but the interior as it appears from outside, as shown in this project from Zack/deVito Architecture.

ME: Do you design through physical models?

JZ: I should… I used to. Sometimes it’s a question of which comes first, the model or the drawing. Do we make a model to represent our drawings, or do we create drawings to represent the model? During school, I would design in model form, and create supporting drawings after the fact.

ME: How would you start, say you have a typical San Francisco lot of 25 x 93 feet?

JZ: It really starts with the client, of course. My very first concepts are a visceral response, in sketches and diagrams, to the client’s programmatic requirements and to the site itself.

I rely a lot on other people, and yet somehow, we’ve ended up with a consistent portfolio. I’ll go to my staff and say, “Here are some ideas and a general sense of the project. Now go draw this. Then I review them, and take out what doesn’t belong.

ME: The drawings are artifacts of a process.

JZ: For me, drawing and the design process are painful and hard. It might be hard even for people who are good at it, though.

These renderings of Zack/deVito Architecture's spec project on Chattanooga St are developed enough to give a clear visualization of the completed project.

I’ll share an anecdote attributed to Greg Lemond [a cycling champion about 10 years prior to Lance Armstrong]. A fellow cyclist thought he looked effortless. He said to the fellow, “It hurts me as much as it hurts you to go up a hill. I just get there faster.” What I mean to say is, design is hard for everybody, even if you’re good at it.

RF: What sorts of skills would someone need to run a design/build firm successfully?

JZ: Hands-on building experience and a strong understanding of materials. They have to be able to make the leap from a drawing to the built thing, and they need to have good management skills, too – above and beyond what might be needed for most architects.

A good computer rendering can give a sense of the interior space, as shown in this project from Zack/deVito Architecture.

ME: How do you handle situations where you’re telling a client to use a particular builder – especially when that builder is a wing of your own business?

JZ: On one project, we got to price our own stuff against another contractor. Our two bids came in incredibly close to one another – $2.84M vs. $2.85M. It was a good validation for us.

We’re still in the infancy of presenting ourselves as a design/build firm. Most of our projects are still architectural design. We need to convince the Marks [Mark English] of the world [his own colleagues, who are other architects] to put us on their list of builders.

ME: Why do you want to do this as a business?

JZ: I can’t not do it! I love the building process, and the potential financial rewards are there. I like the ability to fine-tune without endless Change Orders.

ME: As the builder of another architect’s project, what do you do about the “gray zone of poor detailing? Especially with steel?

JZ: No architect should ever ask me to look at their drawings with steel work! [laughs]

It’s attractive to other architects to have someone who can collaborate on the final details. I’ve actually told people, “Just stop detailing that steel and glass stair. Let us do the fine-tuning to get the details the way YOU want them.” When we build someone else’s project, our aim is to help them achieve their goals.

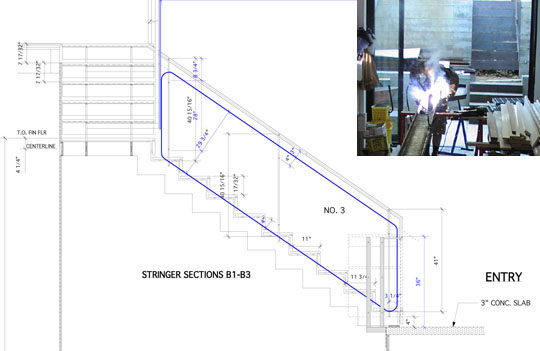

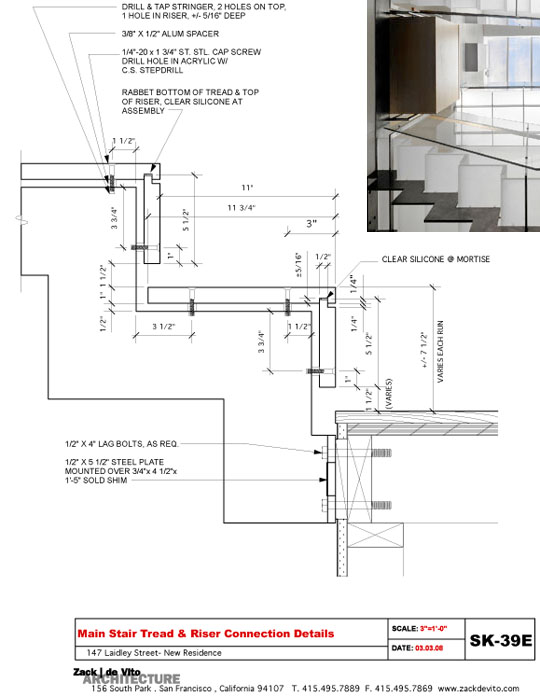

Detail drawing for the stairs from Zack/de Vito Architecture's award-winning Laidley Street project.

JZ: With most architects, if you put down two parallel lines like this, they’ll say “That’s a wall.” But for a builder, that’s useless. How thick is the wall? What is inside, and how should it be assembled?

The things I’m most proud of at the end of the day are my ability to make a nice space, an efficient space, that is well-composed and well-organized. But it always falls short at the end of the day… I always feel we could have done better. I’m never satisfied.

RF: What other architects do you admire? Do you think they are always satisfied with the results of their efforts?

JZ: I think so. There’s a feeling that they would have worked everything out to the point where there could be no further possible improvement.

I really like Tom Kundig, of the firm Olson Sundberg Kundig Allen http://www.oskaarchitects.com/ in Seattle, for his handmade steel gizmos.

Delta Shelter by Tom Kundig. Large, 10’ x 18’ steel shutters are opened and closed with a hand crank.

Aidlin Darling is great, from both a design and a business perspective and Olle Lundberg is another one.

RF: Do you have any pet peeves about architecture, or building?

JZ: Architects who don’t understand their materials. For example, a note that just says “metal handrail”. That’s nonsense. Which metal? Is it nickel, copper, steel, aluminum? How’s it going to be made?

Another example is not drawing things that are real. Everything’s an abstraction. I can only draw it if it’s real. Not putting down two lines for a wall and saying “That’s the wall.”

Or putting in a placeholder early on for things like “bathtub”. Although you may not know exactly which model right at first, most standard bathtubs are 60″ long. So if you never check, you might design a bathroom that’s only 57″ long and then whatever bathtub you end up choosing won’t even fit. There’s no excuse for this when you can go online and get these dimensions in a few seconds.

Sometimes I think that every young architect is faking it. They think they know a lot, but they don’t yet – and they don’t know it. One day I was in a client meeting and I realized: “I’m not pretending anymore. I actually know what I’m talking about.”