Richard Rhodes: Master Stonemason Turns Sculptor

by Rebecca Firestone with Mark English AIA | Interviews

“Stone is one of the most uniquely expressive materials on the planet. As an artist, I strive to think through the material – classical training as a stone-carver gives a unique perspective, similar to doing my scales the way a pianist would. I consider myself a modernist now – but still grounded in a deep affection for, and knowledge of, the classics.” (Photo: Richard Rhodes)

I first encountered Richard Rhodes when he was sharing the secrets of medieval stonemasonry at the Institute for Classical Architecture, hosted by Tucker & Marks in San Francisco over 10 years ago. A master stonemason, sculptor, and architectural stone scholar, Rhodes is the last surviving member of the 750-year-old stonemasons’ guild in Siena, Italy. He’s also done pioneering work in stone reclamation and re-use, harvesting centuries-old stone from Chinese villages that had been condemned to make way for the Three Gorges Dam project.

His lecture was so spellbinding that it stuck permanently in my brain, and every so often I’d write to him to ask him when his book was coming out. And now, he’s certainly not letting the grass grow under his feet – he’s started yet another direction, and for the last 6 years has focused mainly on original works of fine-art sculpture.

Rhodes’ New Book: Stone Expression and Use in the Built Environment

Rhodes’ book, which I haven’t seen but which parallels his lectures, should be out by September of 2017. The so-called “Sacred Rules of Bondwork” were the techniques used to knit stone together to create durable and beautiful stone buildings: palaces, fortresses, monuments, churches – even the pyramids of Egypt. During that lecture, I even asked Rhodes whether he was revealing guild secrets, and he said, “Well, out of respect for the guild and my own training, I waited till all my masters had passed. There’s no one left now. If I don’t share this knowledge, it will be lost.”

Portfolio

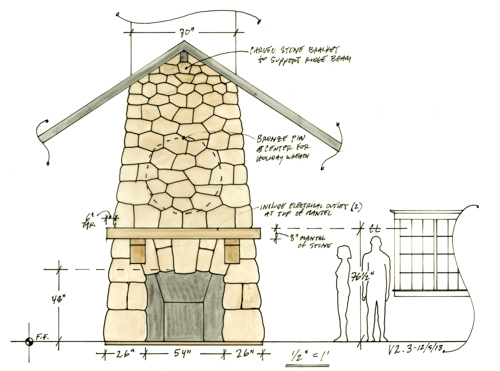

You can see a wide selection of both private and public commissions on Rhodes’ online portfolio. All the projects show both the process of creation and the completed pieces. The works themselves are quite varied: interlocking sculptures, giant stone eggs, a rough stone wall, mosaics, primordial fireplaces, and a selection of major architectural work ranging from 19th century traditional to a free-form sculptured wall that resembles a very carefully crafted ruin.

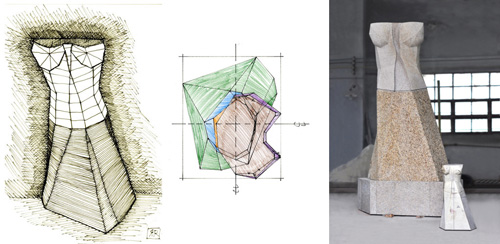

Richard Rhode’s “Sentinel II” is part of a larger “Sentinel Series”, sculptures intended to stand witness in the landscape. Photo: Richard Rhodes

Favorite Artists

Who are some of your favorite artists? I asked. “I’ve been compared to Brancusi, which I consider a huge compliment. Henry Moore is another of my top favorite artists, as well as the Italian sculptors Girolamo Masini and Arnaldo Pomodoro.”

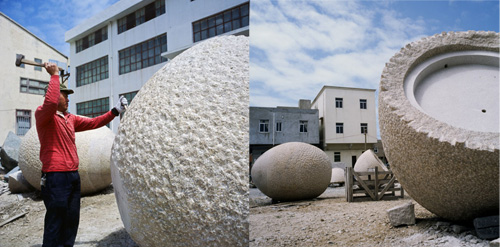

Richard Rhodes hand-fabricated these 35-ton granite eggs for artists Brad and Diana Goldberg. The completed work is installed at the Minneapolis Children’s Hospital in Minneapolis, MN. Photo: Brad Goldberg

Training and Influences

“My training was essentially classical, including an apprenticeship in the operative branch of the Freemasons Guild of Siena, Italy. I consider myself a modernist now – but my work remains grounded in a deep affection for, and knowledge of, the classics.” In other interviews, Rhodes has described the arduous process of being accepted into this guild as a frivolous-seeming American student. He was initially interested in studying “ritualized male behaviors of the medieval guild” and relating it back to his interest in medieval drama, the basis of his graduate studies in London.

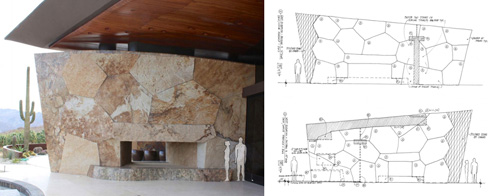

“Four Abstract Volumes” by Richard Rhodes, are unique forms that are integrated within a private residence designed by architect Kristi Hanson in Palm Desert, CA. Photo: Butch Dury

“The Guild was already dying out,” Rhodes said. “All the young men had left for America long ago, and here I was, an American in my tennis shoes, asking for training. They were understandably skeptical… I had to prove myself.”

Mastery of Material

Rhodes’ training might be seen as similar to that of 19th century architects, which at that time required a working knowledge of the 40 or so building products in use. “A 19th-century architect would have cut stone, flashed a chimney, built furniture using joinery, glazed a window, and knit beams together. It was about the physical interaction with the material, and muscle memory as a way to develop and understanding of the essential materiality.”

“My own experience was explicitly grounded in the materials. That training gave me a unique perspective and skill set. It built my expressive capacity with the tools. I think of it as ‘doing my scales’ the same way a pianist would.” Rhodes returned to this theme several more times.

Master sculptor and stonemason Richard Rhodes hand-carved a series of large woven stone screens for a private residence in Hawaii. The home was designed by architect Shay Zak. These photos show early expressive prototypes. Photos: Richard Rhodes

Architects’ Training Shifts to the Conceptual

Rhodes points out that today, there are over 44,000 building products, and it’s impossible for any one person to have hands-on experience in all of them. “Today’s architects are divorced from materials, and their work is more about systems integration: knitting the structural system to the glazing system, integrating lighting and HVAC.”

The New York Public Library as a neoclassical building built at a time when the architects might possibly have had serious hands-on materials experience. Rhodes notes, “The New York Public Library is one of the first modern stone veneers. Despite appearances, the stonework is not structural.”

We discussed the importance of attaining personal skill in building craftsmanship. I noted that architects with a strong construction background still emphasize the importance of having intimate hands-on knowledge of building materials. “The jury’s still out on that one,” Rhodes replied. “Consider work like Frank Gehry’s. They’re almost 2 buildings in one: a 3D form [skin] and then another form inside of that, for waterproofing and system support. Maybe making two complete sets of systems is a waste.”

When I suggested that modernist architects may have wanted to get away from artifice, no veneers, no ornament, just the honest building material exposed, Rhodes added, “…but Gehry’s buildings are striking indications of how that original impulse has been deeply compromised.”

“Embrace”, a sculptural stone artwork from Richard Rhodes, is part of his “Sentinel” series. Note the “invisible” join on the left-hand piece, near the bottom. Photos: Richard Rhodes

Cyclopean Polygonal Veneer

I noticed from the process photos that the giant abstract forms in the Palm Desert home are actually huge pieces of stone veneer. But… isn’t veneer just another form of lying?

“No, absolutely not. Consider that the Romans built using stone veneer. The New York Public Library, a famous Neoclassical building, uses stone veneer that’s 14-21 inches thick. The term “veneer” should be something that is self-supporting and tied to the structure beneath, but the veneer isn’t structural in itself.

“It’s not doing the active work, the heavy lifting. In light of what we now know concerning the life-threatening forces of failing structural masonry, this is a good thing. However, the stonework must LOOK structural. You never look at my work and think ‘Oh, that’s just a veneer’.”

Richard Rhodes’ “Four Abstract Volumes” for a private residence in Palm Desert, CA, uses 550 tons of 9-inch granite veneer, including one of the largest, a huge 9×13 foot block, installed over a massive steel substructure. Architect: Kristi Hanson. Photo: Richard Rhodes

Burningman

In 2010, Rhodes did a sculpture titled “Earthtone” at Burningman – an unlikely place for works of permanence, since their motto is “pack it in, pack it out” and “leave no trace behind”. Why did you go? I asked him. “That see-saw was one of the most interesting and enjoyable things I’ve done in my practice, and my first non-stone sculpture. It created sound when you played on it, and was tuned to the tone of D Flat, the tone of the earth. It was so liberating!”

Stone sculptor Richard Rhodes did one sculpture that uses no stone at all. “Earthtone” debuted at Burningman 2010 as a collaboration with Todd Cole of Strata Landscape Architecture and Marin Fasano. Photo: Richard Rhodes

“We used a lot of woo-woo stuff in that sculpture, because, well, it’s Burningman – go wild or stay home! There are pentagons and the Golden Mean, we just went all out.” Is D Flat really the natural tone of the earth? I wondered. “The theory is that all things in nature, including the earth itself, have a harmonic. When waves hit the shore, and you filter out the white noise, the thudding sound made as the waves impact the earth turns out to be D Flat. It has been conjectured that this is the underlying tone of the earth itself.”

This untitled sculpture by artist Ellen Solod was executed by Richard Rhodes. It’s located at the entrance to Ephrata, Washington. Photo: Richard Rhodes

Rhodes was deeply inspired by some of the artwork at Burningman. “One piece was a wireframe steel piece 60 feet high, a nude dancer titled “Bliss”. That one was privately funded and reportedly cost in excess of $1M.”

Coming Attractions

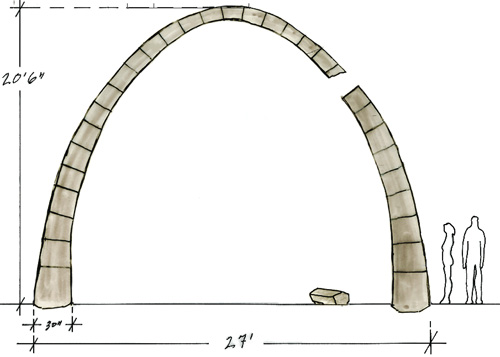

Rhodes shared information on two upcoming sculptures: one that’s in the early concept stage, and one that will be installed next summer at the Yellowstone Club, a private residential ski resort in Montana. All he would say about the concept piece was that it was inspired by the playa at Burningman. Ideally, he wants to debut it at Burningman and then tour it to various sculpture festivals. It’s a very large “gravity-defying arch”.

“Sentinel VI – Connection”, an upcoming stone sculpture by Richard Rhodes for the Yellowstone Club in Montana. It will stand 14 feet tall and 28 feet in diameter. Sketch: Richard Rhodes

So, do you have any really far-fetched or outrageous fantasy pieces that you’d like to build? I asked. “I would like to do an expressive tower like some of Gaudi’s works. Something assembled and vertical would be a great challenge.”

Richard Rhodes shared this exclusive sneak preview of a sculpture he’d like to debut at Burningman – if he can find the right sponsors. Sketch: Richard Rhodes

A self-proclaimed modernist at heart, Rhodes is not interested in re-doing Stonehenge. “When you’re young, you take any job. Perhaps because of all my classical training, I was asked to do a lot of codified vernaculars. It’s like doing your scales as a musician. All that practice was a boon, but now I’m focused on sculptures for THESE times… for OUR time.”

Cultures With Traditions of Stone

When he was salvaging salvaging antique stone from demolished villages in China, he said, “Those were days of legend. It was obviously an interesting time to be in China. There was no banking system. We brought suitcases of cash to pay the workers, and the suitcases were handcuffed to gurkhas (guides), that we hired out of Hong Kong. What an experience!”

Richard Rhodes was deeply inspired by traditional stonemasonry from around the world. This example shows an unusual application of split river stone in Fujian, China. Photo: Richard Rhodes

“To work in China is to work in a culture with a 3,500 year old stone tradition,” Rhodes told me. “There are lots of carvers at my skill level in China, as in Italy, or India. Having skilled workers to help with fabrication is immensely helpful for large projects or very large pieces. Not that each carver is trying to express the same thing, though. Great attention is required to guide the work, and to align it with my artistic vision. As I get older, I’m more particular, and I can feel more clearly what I want.”

Traditional stonemasonry included techniques for purely visual effect, such as this herringbone block pattern in Fujian, China. Photo: Richard Rhodes

Favorite Buildings

So, what are some of your favorite buildings? I asked, figuring Rhodes would wax poetic about elaborately carved churches or landmarks such as the Taj Mahal. Nope… “I’m more interested in the expression of stonework. Elaborately carved buildings are feats of engineering, not necessarily expressive uses of stone.” Instead, he cited the Caves of Ellora in India. “It’s a huge temple complex carved into living rock. There are many other examples of living-rock carving around the world, including Petra in Jordan, churches in Ethiopia, and caves in Turkey. But Ellora really stands out for me.”

Richard Rhodes was deeply inspired by living-rock carvings such as the Ellora Caves in India. Photo: Richard Rhodes

“My favorite stone interior is probably the Treasury of Atreus in Mycenae, Greece.”

The Treasury of Atreus, also known as the Tomb of Agamemnon, built by the ancient Greeks, has a stark and powerful feel to it. Photos: Richard Rhodes

A Team Effort

“When everyone is pulling their weight, and working in their own special genius, one plus one is much greater than two.”

Looking through Rhodes’ portfolio, almost every project includes credits for other design professionals: architects, masonry contractors, landscape designers, artists, engineers. How do you put together a successful team? I wondered. What qualities or skill sets do you need to include in order to successfully create something on a massive scale?

For the public artworks, Rhodes spoke in terms of abilities rather than skill sets, emphasizing vision, technical mastery, and project management. “You need the ability to conceptualize site-specific artworks in 3D and see what works in the particular space where it will be installed. It really has to be something worthy of doing, because it can take a year or even longer to accomplish.”

Stone sculptures such as these stone eggs at the Minneapolis Children’s Hospital involve teams of skilled workers to quarry, transport, carve, and install – and can take months, even years, to bring to completion. Artists: Brad and Diana Goldberg. Fabrication: Richard Rhodes. Photo: Richard Rhodes

Richard Rhodes was particularly passionate about project management. “You have to be a consummate professional: on time, on budget, and you have to deliver. Artists have a terrible reputation for this, and I have come to resent it. A lot of clients avoid dealing with artists because of this reputation, which unfortunately limits our opportunities.” Rhodes observed that poor execution has marred many otherwise promising public art pieces, albeit more so in America than in Europe. “The frequent lack of craftsmanship is inexcusable.”

“Waterworks”, an artistic collaboration between Lorna Jordan and Richard Rhodes, is a public park next to a wastewater treatment plant in Renton, Washington. Photo: Richard Rhodes

For the architectural projects, Rhodes emphasized a client-centered approach. “We all have to remember that it’s someone else’s house. It’s the client’s house. We don’t get to live there ourselves. All we get is the process. The process should be professional and respectful. Ego is an important part of being an artist, so it’s not like you have to throw away your ego. But the ideal team is one that respects the unique skill set that each person brings. Each person should be respected for the parts they have mastery over, and should embrace the mastery that the other team members bring to the project.”

Richard Rhodes’ stone design and fabrication was integral to this finished project, a private residence in Colorado. The design team included Madderlake Designs, Studio Sofield, and JLF Architects, Inc. Photo: Richard Rhodes

Expressive Stone

Over and over, Richard Rhodes returned to the terms “expressive stone” and “stone expression” as fundamental to his philosophy. But what does that mean exactly? “Some of the Incan sites, Ollantaytambo and Saqsaywaman, are truly expressive and awe-inspiring,” he responded.

“But of course, it’s not just the Incan stonework that inspires me. My book looks at the full 4700-year history of expressive stonework, and shares examples from 32 countries. These are mostly unknown sites where dazzling work, much of it never given critical attention, pushes the boundaries of stone as a medium and expresses something fundamental about both the material and man’s ability to find expression through it.”

“Stone is one of the most expressive materials on the planet,” says master sculptor and stonemason Richard Rhodes. This 12th century wall is in Jaisalmer, India. Photo: Richard Rhodes

“Stone is one of the most uniquely expressive materials available. The difference between rock found in nature and worked or wrought stone is striking. There are so many textures you can do with hand tools. Stone is such a visually rich material, especially when layered with patterning. Inca stonework is distinctive, both for its texture and for its freestyle patterning (a result of their hammer-stone technology).”

This unusual fireplace commission by Richard Rhodes, titled “Forest Gathering”, includes hand-fitted stones and a carved bas-relief firebox (not shown). Photo: Richard Rhodes

Rhodes continued, “As an artist, I strive to think through the material – using the material as a medium of expression. I am working to say things with every gesture. The choice of individual stones, color, texture, way of carving – all should be in service to higher ideals. Stone uniquely answers that call. I find it one of the most compelling materials on the planet.”

Stone is Character-Building

In past lectures, Richard Rhodes had spoken of how some countries are stone cultures, and others are wood cultures (or whatever local building material they happened to have available). Does that mean that working with stone can shape the personality or character traits of the artisans themselves? “Definitely. It’s not like it shows up physically so that someone could look at me and say, ‘That guy is a stonemason, I can tell’. But there’s an intractability to stone. To master it, one must work in a slow, methodical process.”

“Working with stone teaches patience and deliberation.” Vernacular stonework from Locorotondo, Italy. Photo: Richard Rhodes

“The legacy promise of stone derives from its permanence. Work that I create now will outlive me, and possibly our entire civilization. Having a time horizon that is so far out changes one’s perspective.” Rhodes described how the process of working with stone elicits personal qualities including patience, humility, and persistence. “I don’t just poke about,” he said. “Every step is planned, then executed, and then re-assessed. It’s a very deliberate way of working.”

There are no do-overs with a 20-ton piece of granite. “If you make a mistake, you don’t just sand it down to fit or put putty on it. You start over. You get one shot and it better be right. The slow and measured progress teaches resilience. I’m a stronger person at my core because I’ve wrestled this intractable material all my life. It forces one to be patient, thoughtful, and decisive.”

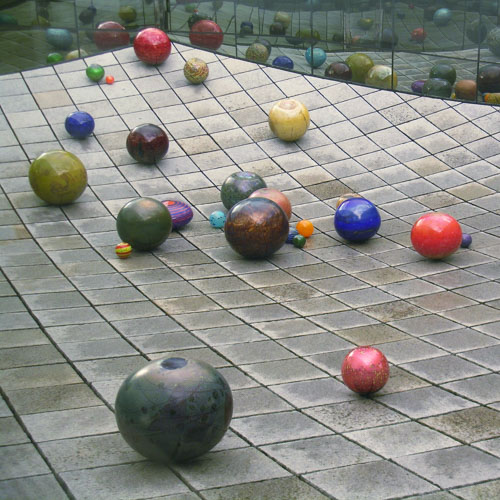

Richard Rhodes’ untitled sculpture is installed in the Tacoma Art Museum. It’s made from salvaged granite, and has included other artist installations. In this photo, the artist Dale Chihuly has created a temporary exhibit called “Nijima Floats” to sit on Rhodes’ wave. Photo: Richard Rhodes

By My Own Hand…

In his lecture, Richard Rhodes had emphasized the inexpressible qualities of hand-worked stone, and of hand-built masonry. “Leave your level at home,” was an old rule for skilled European builders who specialized in working on very old buildings, because of their small irregularities. So, is hand carving really that much better than machine carving? I wondered. “There’s no comparison,” he replied. “CNC has a dead, too-even quality to it – a sterile lack of expression.”

“Of course, it’s OK to use a machine to size blocks, although it’s often faster to split it by hand. I do use saws and other machines, although my work is really defined by the craft’s essential tools, the hammer and chisel.” It was hard to find photos that could clearly show the subtle differences between hand-worked and machine-worked detailing. “That’s what my book is about, among other things. That’s the modern dilemma, systematizing and making stonework economical. Mass-produced work often looks sterile. The material itself has become dull, stripped of expressive potential. I find it alarming. No wonder that we don’t want to inhabit those spaces.”

Openings that frame elements in the landscape draws attention to both the opening and what lies beyond. Design team: Richard Rhodes, Madderlake Designs, Studio Sofield, and JLF Architects, Inc. Photo: Richard Rhodes

In many ways, Rhodes seems to be saying that technology-driven material processing would require a different design intent that would exploit and celebrate the capabilities of CNC or other industrial, mechanized methods, rather than using machines to replicate something else as a sadly inferior copy. It’s a bit like presenting vegan barbecue as “fake meat” instead of developing an entirely new cuisine to bring out the qualities inherent in the actual ingredients.

Rhodes responded, “Exactly!”