Matarozzi/Pelsinger: Contemporary Builders and Craftsmen

by Rebecca Firestone with Mark English AIA | Interviews

“We like contemporary architecture. The buildings are refined designs that minimize fluff. Their lack of ornament actually increases their attraction for us as builders. There’s an organic feel to a well-thought-out modern building. We believe in the adage that form follows function.

“The best workers bring a dedication to craft to every job. You can tell who has it by watching how someone works on the job site. Watch how he or she goes about problem solving. Can he solve the problem and keep working? Can he apply what he learned yesterday to solve a new problem today? Some people need to be shown every single time. I look for other things, too. Does he keep his tools organized? Does he know how to work in rhythm? Does she anticipate what’s coming next? It’s having an intuitive feel for the job. I’m always watching out of the corner of my eye, to be part of the rhythm and flow of the team.”

A few weeks ago, we visited the offices of Matarozzi Pelsinger and spoke with Lawrence Motta, Dan Pelsinger, and Dan Matarozzi to get a builder’s perspective on what it means to create good architecture. The meeting opened with some Monty Pythonesque banter – but for all their lighthearted humor, they’re a pretty hard-core bunch when it comes to the quality of their own work. (Speaking of Monty Python, check out the Python Architect Sketch, which you can see right here on YouTube. It’s a riot!)

Speakers are credited by their initials: LM (Lawrence Motta) DP (Dan Pelsinger) and DM (Dan Matarozzi).

What makes Matarozzi Pelsinger such a good company? What makes you so much better than, say, the Joe Average Construction Company?

LM, DM, DP: It’s not just the amount of experience that we have. It’s what we’ve learned from that experience – how to tell smoke from fire. As a company, we emphasize a strict adherence to decision-making with consensus on all important issues. For example, just yesterday we discussed how we maintain our list of qualified subcontractors. It wasn’t about who was on the list. It was about HOW we maintain that list, the nuts and bolts of the process itself. How do we choose, recruit, train, retain, cultivate, evaluate, and how do we communicate those evaluations internally. We solicit feedback constantly from our own people: field operations, project management, and estimating.

Matarozzi/Pelsinger Builders’ new headquarters building was completely transformed during its renovation. A perforated zinc screen covers the front facade, and the original interior beams were carefully cleaned to match the pristine modern interior detailing. Architectural design: Aidlin Darling Designs. Photos: Richard Barnes

That sounds like the Capability Maturity Model from Carnegie Mellon. That was a way to measure the quality of organizational processes in terms of repeatability and knowledge transfer. Turns out that most companies were still at Level 1 – chaotic, ad-hoc, individual heroics.

LM: Competition drives introspection. We are cutting edge in terms of our process, and we have an unwavering commitment to the quality of our own work. Quality isn’t just about having expensive materials and complicated products. It’s really about HOW you put them together. This is a company-wide culture.

Typically in construction projects, the lowest bidder gets the contract, but the resulting teamwork often falls short.

LM, DM, DP: We recognize that we are in a service industry. We have to coordinate with all these other players: architects, clients, subcontractors, inspectors, consultants. You need a team approach, and you need professionals who can go the extra mile.

Can you give specific examples of quality details in construction?

DM: Here’s one trick I learned from an old carpenter. On wood shingle facades, look for cut shingles. If they didn’t install the shingles correctly, the rows of shingles won’t align with the door and window openings and they’ll have to trim the shingles over those openings.

A good wood shingle facade should align with the window and door openings without the need for trimming a row in the middle. This example is from Pacific Shingle.

LM: Or, take a look at the switch plates right here in our building. The screws are aligned. If I go into a job and see things that are not aligned we will fix them. A client may not consciously see that all the screws are lined up, but subconsciously they can feel that a home is well built. That’s our culture: attention to every detail, a scrupulous sense of honesty, and an open book.

Matarozzi/Pelsinger Builders won’t leave anything misaligned on a job, and they won’t leave a mess afterwards.

There’s medication you can take for that, you know…

So, do you remember flaws or mistakes on past projects? Do they keep you up at night?

Yes!! [says everyone]

LM: I’m a field guy with 25 years experience, and I still get bothered remembering stuff from years back.

Do you have any advice for architects? Do’s and don’ts, or things you wish more architects would do, things you wish they knew more about?

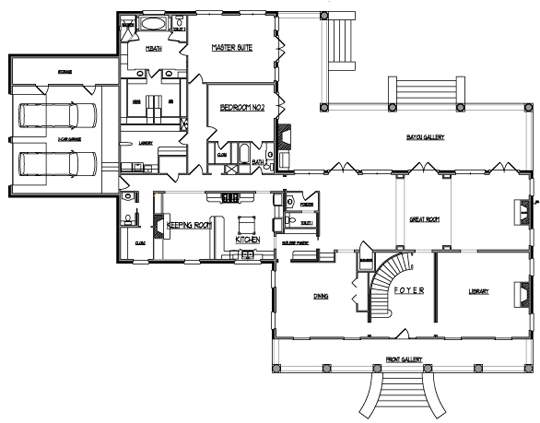

LM, DM, DP on drawings:

- Don’t give us napkin sketches and then ask for accurate, detailed pricing. Especially don’t ask us to bid competitively based on napkin sketches. It happens all the time!

- For remodels, put the existing and new drawings on the same page of the drawing set so we don’t have to constantly be flipping back and forth to see what’s changing.

- Label both horizontal and vertical grid lines on your drawings.

- Make sure the structural and the architectural drawings match up.

- Make sure the specs match the plans.

- Bubble your changes.

- Get good software and render in 3D so we can see how the house goes together.

LM, DM, DP on detailing:

- Detailing is important, particularly in cutting edge designs. In modern design, there’s no such thing as “typical” details. Nowadays you might build to a 1/16″ tolerance – that’s not historical, except in special cases like traditional Japanese timber framing. The builder needs to have a very high level of competence and mastery in order to successfully execute modern designs. Of course, the scope of the project can dictate how much detailing you can do. If it’s a single bath remodel, you can treat it like a science project and show every detail. With a 6,000 SF house with 4 bathrooms, you can’t detail it all.

In this 7,000-SF Pacific Heights renovation and addition, Matarozzi/Pelsinger Builders upgraded the foundation, framing, plumbing, mechanical, and electrical systems, as well as doing a full interior renovation. Architectural design: Charlie Barnett Associates. Photos: Mark Darley

LM on what an architect should know:

- Take the time to understand structural systems.

- Understanding building traditions is important. A lot of post-WWII architecture is about form over function.

- Architects should understand how things work, how things go together. Understand how, but don’t be constrained by it. The understanding engenders respect, and a willingness to understand the process of building as a collaboration, a team effort.

This condo renovation was built by Matarozzi/Pelsinger Builders. Details include floor-to-ceiling pivot doors and a custom glass handrail. Design: Marnie Wright

LM on materials and flooring:

- When choosing materials, do your homework. The “wow-cool” factor is not enough. Examples: Don’t specify veneered plywood for stair treads, because it de-laminates within a few months of use.

- Don’t use solid flooring over radiant heat, because it will buckle. And don’t just rely on a 3 x 3 sample from the flooring subcontractor; it’s not going to look as perfect. Even small amounts of thermal expansion and contraction can really add up on a large surface area.

Matarozzi/Pelsinger Builders did a complete interior build-out of this two-story San Francisco penthouse, including structural alterations, cantilevered steel and wood stairs, and telescoping doors in the master suite. Architectural design: Joel Sanders. Photos: Rien van Rijthoven

DP on listening to your clients:

- Listen to your clients. What do they REALLY want? How do they really want to live? You have to constantly be educating your client about what’s going on. Architects need to lead and educate their clients on the implications of delayed decision-making. Help them to understand the critical path concept.

The penthouse and kitchen from the San Francisco loft renovation built by Matarozzi/Pelsinger Builders. Photos: Rien van Rijthoven

Does anyone draw too much detail these days? Is that ever a problem?

LM: Is anything overdrawn? Not these days. I remember in the old days before computers, we’d see STACKS of drawings and details. Not so much today. People do want beautiful intricate designs, but they don’t want to pay for drawing all those details. Now we have to work to extract that information.

DP: As builders, we need to know when to ask a question, when to solve it ourselves, and when to suggest a solution vs. just asking questions. That’s the difference between a master builder and an apprentice. A master builder knows how to lead and offer solutions.

This new contemporary ski house featuring custom sculptural steel trusses, radiant heat, and a variety of custom details was built by Matarozzi/Pelsinger Builders near Sugar Bowl Resort. Architectural design: Mark Horton Architecture. Photos: David Duncan Livingston

How do you conserve materials?

LM: My granddad would pick up old bent nails and hammer them straight. He’d say, “That’s good nail.” You can see in the old buildings how they re-purposed material sometimes.

But new building technologies are coming out all the time. How can anyone keep up?

DM: You have to understand where you come from. Today’s houses look the same on the outside, but inside the walls, they’re completely different. Take waterproofing. Rain still falls the same way it did in ancient times, but buildings are different. Today’s building envelopes are less air-permeable.

DM: Older San Francisco houses were built using only sheathing boards. No building paper. Sometimes we do remodels and have to open them up, and they’re usually in fine shape. These old buildings were good at keeping the rain out, but not so good at keeping warm air in. The air movement, which might have reduced mold, meant they were drafty and cold, and they had no central heating. So they had more walls, and people just wore more clothing indoors. Now, we are confronting old conventions about how a building is put together.

DM: A lot of it is re-adapting old techniques to new buildings. The Courthouse Building has a new seismic system, neoprene bumpers sliding on rails. But there are ancient temples in Greece and Sicily that use the same general principles. Or take the old steam radiators that most East Coasters grew up with. I re-purposed some old steam radiators and used them for radiant heat instead. They carry a constant stream of 120 degree water now, instead of steam.

DM: Architects sometimes want to stretch materials to their limits, sometimes making them do things that they were never intended to do. You can’t always predict how a new material or assembly will respond in real conditions, and there may not be 5 years to test a prototype.

This home, originally designed by Ernest Born, was later remodeled by Aidlin Darling Design. The use of Cor-Ten steel as a finish material is a relatively new phenomenon. Matarozzi/Pelsinger Builders did the construction for the renovation.

What do you as builders consider to be “good design”, from both a practical and from an aesthetic standpoint?

DM: It’s about taste as much as experience. We like contemporary architecture. The buildings are refined designs that minimize fluff. Their lack of ornament actually increases their attraction for us as builders. There’s an organic feel to a well-thought-out modern building, because the structure is revealed as part of the design. Good design shows an understanding of materials, and how to meld those materials together. We believe in the adage that form follows function.

DP: Every architect wants to do a new thing. The Guggenheim in Bilbao is a great building. One wonders, “Wow – how did they think of that?” It takes your breath away. Well, that Guggenheim wasn’t cheap to build, with all that titanium. I guess the Parthenon wasn’t cheap either.

In the Lake Street Corridor renovation, Matarozzi/Pelsinger Builders performed extensive foundation and structural work together with modern finishes including extensive use of steel and glass. Architectural design: Kuth/Ranieri Architects. Photos: Cesar Rubio

LM: I’ve eaten my words, too. I’ve looked at designs and said, “That’ll never work.” But then afterwards, I can see that it does work. A good architect can defend his or her ideas.

Additional views of the Lake Street Corridor renovation built by Matarozzi/Pelsinger Builders. Photos: Cesar Rubio

DM: Architects want to look amazing on a limited budget. It’s a bit like a sport. People performing in circumscribed physical arenas, doing specialized tasks that are highly defined. Creative within tight parameters. It’s different from painting on a blank canvas, which has far fewer limitations from physical laws and program functionality.

Architecture is a bit like a spectator sport: amazing feats performed in a circumscribed physical arena under strict rules.

Tell me more how you feel modern architecture is organic. I used to feel that it wasn’t – didn’t use organic materials or shapes. Steel and concrete aren’t “organic”. And no one was using wood in East Coast modernism, at least not in the stuff I remember seeing featured in The New York Times Magazine.

LM: I’ll compare two projects. One by Aidlin Darling, the Cor-Ten cube on the Great Highway is organic because of its indoor/outdoor focus. It feels like you’re literally floating in the cypresses. There are no distractions within to take away from nature outside. It feels like a tree house. The other was for clients who were not interested in bringing the outside in. It’s an environment unto itself. Not an organic feel. But still a successful architectural piece.

Another view of the Great Highway renovation designed by Aidlin Darling and built by Matarozzi/Pelsinger Builders. The outdoors is brought in so that the home feels as if it’s floating among the cypresses.

DM: Here’s another one: a 2,500-SF apartment on Nob Hill in San Francisco.

A disciplined and restrained palette gives this Nob Hill condo renovation an integrated, organic feel. Architectural design: Garcia Tamjidi, Michael Garcia, and Farid Tamjidi. Builder: Matarozzi/Pelsinger Builders. Photos: Joe Fletcher

DM: Restrained palette, doesn’t make a statement, but it works as an integrated piece. Everything on the interior is interrelated.

Additional views of the Nob Hill condo renovation built out by Matarozzi/Pelsinger Builders. The restrained palette acts to highlight the art on display. Occasional touches of color elsewhere follow the same disciplined, minimalist approach. Photos: Joe Fletcher

What about bad design?

DP: Bad design has disjointed themes, arrhythmia, floor plans that don’t flow. It’s like a museum with each room from a different era. Contrived as in “let’s take this from Dwell… and that from Better Homes” or “Oh look! Crown molding!” Contrived as the opposite of organic. Even an ice cube is organic [self-assembled].

“Even an ice cube is organic,” says Daniel Pelsinger of Matarozzi/Pelsinger Builders, because water follows the same laws every time it freezes.

Why are competitive bids bad? Or when are they a bad idea?

LM & DP: When you don’t know what you’re building, if you don’t know the scope. In other words, if value engineering has not accompanied the design process. Value engineering means both a complete set of plans, and at least some realistic idea of what it’ll cost. You can get this as a gut check from an experienced building professional – ideally a contractor rather than an estimator. Specs are important – if you set an architect loose and THEN give it to three contractors, it’ll often be over budget.

LM: If you don’t quite know the scope yet, it’s better to bid on general conditions like billing rates, markup, and staffing levels. Otherwise you could be comparing apples to oranges. A contractor who bids low may not have enough onsite management to do a good job. Allowances help, too. If an architect puts together a list of general contractors for bid, I like to level the bidding process by giving the same allowances to everybody for things like doors and appliances.

Another example of a modern steel detail requiring precision in building. This remodel of a Green Street home in San Francisco was built by Matarozzi/Pelsinger Builders. Architectural design: Holly Hulburd Design

What about estimating based on average cost/SF? Or asking questions like, “How much house can I get for my stated budget?”

DP: Still too variable. But as a client, you shouldn’t be afraid to give a budget. Some clients don’t want to, but look at it this way. If you’re buying a car, you have to know approximately what you want and how much you have to spend. Do you want a BMW or a Yugo? Do you have $5,000 or $50,000? Budgets always climb, mostly due to changes in scope or discoveries during remodels. We advise clients to hold a contingency for changing their mind, and for discoveries.

Along with their own headquarters office, The Flora Grubb Gardens project shows a deep commitment to green building from Matarozzi Pelsinger Builders. This commercial nursery features sustainable building design and materials, including a prefabricated metal frame, extensive toxic cleanup, 80% power needs from solar, and the use of recycled or reclaimed materials where possible. Design: Boor/Bridges Architecture.

What do you think of the design/build business model?

DP: We don’t do design/build, except for our Special Projects Division where we partner with a designer of our choosing. We give the client 3 names. We manage the design services. Even a kitchen remodel needs a design professional.

Who are some of your heroes?

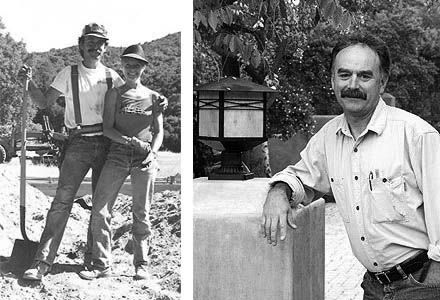

DP: Turko Semmes of Semmes & Company. When I was at Cal Poly I worked half time with him, full time in the summers, as a carpenter. He was doing sustainable passive solar building in the late 70s, using new materials such as rammed earth, straw bale, and trombe walls. He had a great open attitude towards problem-solving. We were marginalized back then as “green builders”. It’s great to see that what Turko was preaching then is now mainstream.

He’s still around. www.semmesco.com

DP: The industry is different now, but the people I remember are the unsung heroes who slogged it out every day. We glamorize field work but it’s often drudgery. There’s a book called The Snow Leopard by Peter Matthiesson about a guy who went trekking in the Himalayas. He made friends with one of the sherpas who carried 70 lbs and he asked the guy why he was so damn cheerful all the time.

The guy answered like a Buddhist: “I serve the task, not the taskmaster.” That’s what the best workers do. They bring a dedication to craft to every job. In our office we do it that way too. The relationship is not between you and your boss. It’s between you and the work itself.

This Clay/Arguello Street renovation built out by Matarozzi/Pelsinger Builders features extensive detailing and a custom window wall. Architectural Design: Peter Pfau Architecture

I always thought work ethic came from upbringing? Is it nature or nurture?

LM: My grandfather was a concrete worker who came from Italy. He worked his butt off. My heroes all worked hard. I remember watching my grandfather using his lathe, then he’d show me his hands and how they had no splinters. I was fascinated watching him work with wood, he had such a passion for it.

LM: My first boss Al, in 1979, was another person who taught me a lot. I was a laborer, and on my first day he told me to move a pile of lumber from the bottom of a muddy hill to the top. He measured the crook of my arm and told me that I could fit 15 2x4s and to carry it like this [demonstrates]. It was more efficient. Not more comfortable, but that’s what the job demanded.

Efficiency on a job site means never going up the stairs empty-handed, and carrying a full load each time.

DP: This attitude towards work, towards solving problems, is not something that can be taught, really. You can tell who has it by watching how someone works on the job site. Watch how he or she goes about problem solving. Can he solve the problem and keep working? Can he apply what he learned yesterday to solve a new problem today? Some guys come to a roadblock and they need to be shown every single time. I look for other things, too. Does he keep his tools organized? Does he know how to work in rhythm? Does she anticipate what’s coming next? It’s having an intuitive feel for the job. I’m always watching out of the corner of my eye, to be part of the rhythm and flow of the team.

According to Matarozzi/Pelsinger Builders, really good teamwork is what distinguishes the best from the rest.

Any stories about project from hell that you brought back from the brink of disaster?

DM: On one project, the client fired the project architect right before construction, and the rest of the design team wasn’t up to the task. We had 300 RFI’s and a very challenging design. It turned into one of our showcase pieces and a very supportive client. So what did the architect do wrong? Well, there were several design flaws that had to be corrected. One was a glass curtain wall with no ventilation, no way to clean it. This meant MOLD could grow. It’s a three-legged stool [architect, client, builder] and if any one of those legs is weak, the project is in trouble.

On this North Point condo renovation, the logistical considerations were almost as challenging as the execution itself. Architectural design: Craig Steely. Photo: Rien van Rijthoven

Do you have any red flags that, when you see them, you know NOT to take on the project at all?

DP: Generally, it’s a bad sign when the client is fishing for a number. It means they’re probably going to another contractor. And people who are unprepared. I remember one project we did that looked great on the surface. Great architect, great client. Then halfway through, the client brought in “her” contractor as construction manager. We knew he would steal the contract, and sure enough that’s what happened.

Matarozzi/Pelsinger Builders performed a complete renovation on this 5,000 SF Los Altos home. Amenities include Lutron Homeworks home control system, a chef’s kitchen, and solar system. Architectural design: Mark Horton Architecture. Photo: Rien van Rijthoven

LM: It’s a question of ethics. We have this problem too, where we are in charge of awarding work to one bidder or another. A subcontractor might call us and ask why they didn’t win the bid. They ask, “Well, how did I compare?” But we can’t tell them. We can’t give out that information, because that would not be playing on a level playing field.

Randy Deutsch

08. May, 2010

Amazing interview – a great deal of valuable information and insight here. This ought to have wider readership. Especially love the question and responses for “Do you have any advice for architects? Do’s and don’ts, or things you wish more architects would do, things you wish they knew more about?” Architects don’t generally think of asking this question often enough and would do a world of good – for themselves and the profession – if they did. Excellent!

.-= Randy Deutsch´s last blog ..55 Ways to Help You Evolve as an Architect =-.

Matarozzi/Pelsinger Builders featured on “The Architect’s Take” « Bay Area Green Building Blog

10. May, 2010

[…] The Architect’s Take, a popular blog by our friend, Mark English, and his colleague Rebecca Firestone, features Matarozzi/Pelsinger Builders. Rebecca interviewed Dan Matarozzi, Dan Pelsinger, and Lawrence Motta, all of whom have years of expertise in the building. In this article they share their thoughts about design, craftsmanship, and the making of skilled builders and architects. Click here to read the full interview: https://thearchitectstake.com/interviews/matarozzipelsinger-contemporary-builders-craftsmen/ […]

Michael S Bernard

25. May, 2010

This is a compelling interview. The transparency of the responses reveals a willing collaborator for the most challenging phase of any project: transitioning from abstract symbols to built form.