Craig Steely: Steel and Light

by Rebecca Firestone with Mark English AIA | Interviews

“My own work now, it’s all one house, just done over and over. I see a connection between one idea to the next – I’m always exploring contrasts along similar lines: opacity-transparency, heaviness-lightness, action-reaction. The ideas can morph to suit the circumstances, and they get refined from one project to the next.”

– Craig Steely, Architect

Part surfer, part engineer, part artist, part prophet – how else can I describe the simplicity, the evocative nature of Craig’s designs and his fearless approach? If there’s such a thing as a contemporary West Coast architecture with a clean Zen sensibility, Craig Steely might be a good exemplar. The word “avatar” doesn’t really do justice to his down-to-earth, straightforward demeanor. He and his wife both could be some glamorous Hollywood celebrity couple – at once elegant and informal – but their charisma really comes from a deep-rooted stability, a sense of health and vitality, and a freedom from inner hang-ups.

Mark English, founder of The Architect’s Take, had long been intrigued by Craig because of their shared academic background as Cal Poly undergrads. Like many top-flight schools, Cal Poly has its own mystique, a blend of artistic and engineering rigor, which leaves a stamp on its students. And, both Mark and Craig share a second passion: a reverence for the Classical architecture of Italy, particularly Florence.

The following interview took place in two parts: the first conversation between Rebecca Firestone and Craig Steely; the second part was a professional dialogue between two colleagues.

Interviewer’s comments appear in italics.

Where did you grow up?

I grew up on a farm in northern California. Very rural, we did everything for ourselves: a lot of fixing, building, making things. My Dad liked to customize everything, specialize or “improve” it to what he needed. If something broke, we put it behind the barn to save it for parts. He and I were constantly modifying tools, constantly tinkering. The folks on my Mom’s side of the family are all very artistic. I liked to draw and they encouraged me. It was this love of drawing that drew me to architecture.

Craig Steely made a splash with his "Lava Flow" series, built in Hawai'i on actual lava beds. The first one, "Lava Flow 1", was for San Francisco designer Robert Trickey. Yes, there's always the risk of new lava rolling down someday, but apparently, it's not so imminent as to discourage either Steely or his many satisfied design clients. Photo: J.D. Peterson

If you loved to draw, why didn’t you become a fine artist?

Maybe it was the customizing part that I liked – customizing things with the goal of creating usable components. “Custom anything” was our family motto. The difference between art and architecture is that I see art as being more self-referential, whereas architecture is a conversation with other people, other collaborators.

Craig Steely's wife, fine artist Cathy Liu, painted this “custom anything” image for a joint show they had together at Mollusk Surf Shop a few years ago (please check them out at http://mollusksurfshop.com/). The original photo was from a 1970s T'ai Chi book that Craig found at a Hawai'i flea market.

Celebrations of the DIY ethos have continued, through events like Burningman [and Maker Faire]. The thing with Burningman is it teaches you about failure. You can work on an idea all year and then it blows down 5 minutes after you get there. You have to be willing to prototype, and be patient, not give up.

That’s how I feel about my own work now. It’s all one house, just done over and over. I see a connection through all of them, between one idea to the next – I’m always exploring contrasts along similar lines: opacity-transparency, heaviness-lightness, action-reaction.

[After reviewing Steely’s work during the writing of this article, I felt that each idea or vocabulary element was like a musical theme, and the projects as a whole were a composition that wove each theme and counter-theme together. There’d be a theme, a development, a transition to something new – and then, later on, a return to an earlier theme but with a new aspect. – RF]

Craig Steely's progression of ideas from one "Lava Flow" house to the next is not exactly linear - more like cycling through several interwoven themes. Above photos are both "Lava Flow 2" which celebrates a lightness and translucency of material. Photos: J.D. Peterson

How do you go about approaching a new project?

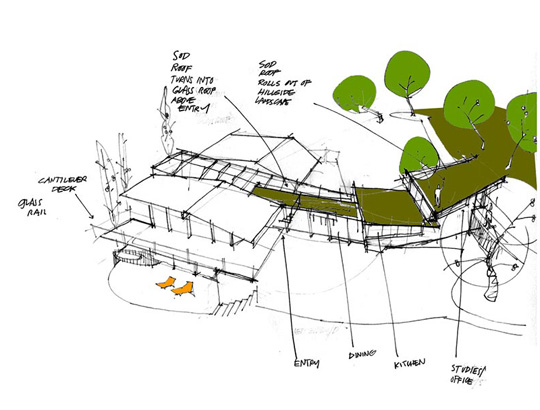

I have a sketchbook of ideas that are just waiting for a project to happen. The ideas can morph to suit the circumstances, and they get refined from one project to the next.

[We drifted to some discussion of music. Craig’s had some exposure to Indian music through a cousin who spent time in India studying with a music master. We compared a few notes on Indian and Middle Eastern musical theory. The life in Hawai’i seems to involve a lot of impromptu jam sessions called kanikapila. Craig learned to play bass so he could contribute to these jam sessions, since usually these gatherings didn’t have a bass player. – RF]

Back to structural elements and systems. I see the design as a holistic process. The entire project team gets excited about each new design. The structural engineer really has to take the project to heart, just as much as the architect does. Everyone has to give it their best – not just protecting themselves. The last word is that everyone on the team is accountable, including the client.

Craig Steely works closely with structural engineers to make the steel framing as light as possible. In "Lava Flow 5", the framing was actually assembled in prototype fashion in San Francisco prior to being shipped to Hawai'i. Photo: Craig Steely Architecture

What makes a good client?

To me, a good client is someone who’s interested in the process. Someone who really WANTS to be involved. I demand it, actually. Someone who enjoys the process as much as the product, someone who sees it as transformative, challenging, and enjoyable. I only have good clients because I’ve set up my studio in a way that I only have to work with people that I like and respect. Seems obvious… the point of taking only good work is that you’re more invested in it. I love what I do and don’t want to get burned out. I’m very protective of this and I don’t want bummer clients or bad jobs to bring it down.

Craig Steely's home office helps set the tone with new clients. Left photo shows his office on the second floor. Right shows the front entry, including a custom-made door with translucent inserts. The door was actually made from reclaimed surplus materials. Photos: Rien van Rijthoven

Doesn’t turning down work keep you from expanding your firm?

I’ve never thought you have to be a big firm to create meaningful work. Architects as a rule are future thinkers, but they need to stay more in the present. I’m all about focusing on the work that I have right now. There’s a sense of grandiosity about the image of a big office for its own sake, but that doesn’t always serve. From experience, and from becoming more secure with my own abilities, I’m more in control by being less controlling. When you relinquish some control, you are free to let other people do what they’re good at. It’s not just about pulling down an hourly wage.

Clean lines of sight where the eye is guided by the alignment of striated materials is one theme that emerges over and over in Craig Steely's designs. This one is "Lava Flow 3". Photo: Cesar Rubio

Tell me more about your present office space here at Beaver Street.

When I was first starting out, I renovated this house we’re in now. It earned some good press and publicity, which got me my first commissions. But then we outgrew it. So we tore it down to the ground and started over a second time. People thought this was shocking. It had been in books!

Craig Steely re-did his Beaver Street house twice. The first was a more conventional Edwardian intervention, but the second remodel, shown here, represented a sea change in his design approach. Note that although the facade is distinct from the Victorian right next door, no neighborhood objections were raised - practically a miracle in San Francisco. Photos: Rien van Rijthoven

[Unusually for San Francisco, the approvals process for the second Beaver Street remodel went smoothly, with no objections raised by neighbors. The fact that Craig had already known his neighbors for years was a big factor. We discussed projects where out-of-towners would come in, buy a house in some nice area of town and then try to max it out – only to be stymied by stiff neighborhood opposition. Good relations may not be something that can be created in an instant; it’s something to cultivate over a long period of time. – RF]

What exactly don’t you like about the first remodel that you did here?

The first remodel kept the proportions of the existing Edwardian and was mainly repairing other people’s mistakes. The scope was limited by our budget and the fact that I didn’t know enough about construction to really tear it down to the roots. It cost only $17K! We did most of the work ourselves. We opened up the space to light, enclosed a back porch, added translucent display cabinets to the walls. We rebuilt a lot of objects recycled from Urban Ore in that first remodel. At that time, I loved to build something based on a part that I had found. You could say that first remodel was “hot-rodded”. But those same ideas about transparency, implying space, and attention to the interstitial spaces – I’m still working with those same concepts today.

By the time "Lava Flow 5" came along, Craig Steely had refined his vocabulary further: lightness, clean lines, openness.

What do YOU think constitutes good design?

For me, good design comes down to proportion and balance on all levels: visual, intellectual, functional.

"Skateboarding is all about finding the perfect line and flow," says architect Craig Steely. He enjoys both surfing and skateboarding.

Any pet peeves?

Fear-based decision-making. At some point you need to take a risk.

How do you talk people out of a fear-based mindset?

Look at this project, Lava Flow 4 on the Big Island in Hawai’i. It’s an all-screen house. The clients had said, “We want simple!” – and then it got complicated. They wanted roll-down doors for weather protection from the storms on the Kona coast. I had to talk them out of it, and their neighbors, too. During construction, the neighbors would come by and comment, saying, “You’re making a terrible mistake!” But there was protection, both from the surrounding trees and from overhangs around the porch.

The clients for Craig Steely's "Lava Flow 4" were initially very concerned about getting wet in an all-screen house, and so were their neighbors. Eventually they decided in favor of simplicity - no roll-down doors needed. Photo: John Granen

“So what if it doesn’t work?” the clients worried. And I responded, “The worst that will happen is your furniture will get wet.” And they said, “Oh, is that all? OK, then,” and they were fine with it, once they knew what the risk really was.

How do you deal with challenges such as objections from a neighborhood association?

In order to be an architect, you have to be an optimist. Always, after an excruciating project is completed, we all say, “Oh, it wasn’t that bad,” because now it’s over. One challenge is to remain civil and effective when things do happen, such as when neighbors come forward with objections. Don’t make it a pushing match. You have to find common ground. It’s about communication skills, and staying focused on communicating your point.

[At some point we wandered briefly onto the subject of surfing, about learning to recognize wave patterns and going along with them. You can’t control a wave. “Go with the flow” as they say, right? Surrender as a method of control. – RF]

In another amazing maneuver, Craig Steely worked with a conservative San Francisco historic preservation association, convincing them to accept a very cutting-edge facade on an otherwise traditional streetscape. The design includes transom portholes in the front glass curtain wall, and adjustable vertical louvers on the side.

In San Francisco, neighborhood groups can have tremendous power. They can stop a project completely, and many homeowners have spent tens, or even hundreds of thousands of dollars, only to be shot down during a design review.

You have to express respect for the neighbors’ opinions, whether they are about architecture or politics. You have to work with the neighborhood groups to make them part of the process. You have to maintain a level of decorum, discretion, and respect. You need the ability to communicate with people even when you don’t agree with them, to find some common ground. I had to convince them that my heart and soul was really in the project. So now a very modern building is going up there and everyone’s totally into it.

Ultimately, we prevailed in the design review by being more than reasonable. Compromise is a good thing, and it can actually strengthen the project in the end by providing better neighborhood context. You need broad shoulders, from which to give. We redesigned the project over and beyond what the association had requested. It ended up as a better project because of those compromises. With any design review board, you have to convince them of the care, intent, and interest that you are putting into each detail.

The "Carr Apartment" project by Craig Steely was a re-do in an existing apartment building, featuring a custom light wall/video installation. Photo: Rien van Rijthoven

What did you get out of architecture school?

The best thing I got out of architecture school at Cal Poly was gaining the ability to motivate myself. Another thing that stuck with me was the skill to evaluate my work on my own terms. Is the design successful to me? Certain school projects that I did got accolades, but other projects that went unnoticed were much more satisfying and successful to me. It’s the same with my work today.

I remember best the professors who challenged us to be self-motivated, and then gave us the freedom to run with it. Terry Hargrave, John Lange – and in Italy, Christiano Toraldo and Gianni Pettena. There were some amazing studios, too, that were all about drawing and painting. Vern Swanson, a watercolor instructor; Eric Vartiainen for drawing, who was a student of Alvar Aalto.

Do architects need to know how to draw?

For me at least, it’s very important. I think people who can draw have a certain grace to their design process and how ideas come together. I spent a lot of time in school learning to develop a physical connection between the eye and the hand. It’s just the way I work. My wedding ring has a hand and an eye on it, because the hand and the eye are so closely related in the act of design.

What type of person do you like to work with?

In terms of whether schools teach the right skills for the workplace – I don’t hire people right out of school generally. What I look for in a potential employee is character and intelligence. A person with character and brains can learn anything, pick up any new skill.

Is it really such a good idea to be friends with your employees?

It works for me. It’s a matter of communication. I look for people I can really get along with. With an office right in my home like this, it’s very close quarters. There’s no place to hide. There has to be trust. That applies to moonlighting as well. Sometimes I get projects that I don’t want to do, and I’ll give those projects to my staff. I don’t understand offices that restrict employees from working on their own outside the office. You know people are doing it, so why set them up. Don’t force your own people to be dishonest.

In this office, we are pretty loose about working hours. Everyone knows what needs to be done and by when. The people who stay are the ones who respect this. There’s a sort of internalized work ethos in a well-functioning team. Putting things back where they belong so that the next person doesn’t have to go hunting for it. My dad called that “knowing how to work” and he meant that on a construction team, one person would already have the tool ready for you.

How do you work with builders on your projects?

The usual architectural process is to send a project out for bids and choose based solely on cost [without considering any difference in quality standards among the various bidders]. But if you can establish trust earlier, it’ll be a better project. The owner should establish clear expectations early on, get the contractor involved earlier on, walk through some of their projects if possible. I have three contractors that I like to work with, categorized by project cost. Clients choose which one works best for them based on their level of expectation.

Even though Craig Steely claims he's always doing the same house over and over, it's clear that there are several parallel themes or "families" emerging, possibly in response to the various California or Hawai'i locales. The "Gipsy House" is located in Northern California. Photo: Cesar Rubio

How do you interview with potential clients?

My house is a litmus test for potential clients. They come and visit the office, right here at home, and if they like it, they’ have a good idea of what is important to me. It’s a long client interview process, on both sides. There has to be chemistry. And how do I know it’ll be a good client relationship? Lots of experience, lots of mistakes. It’s like surfing. At first, a new surfer doesn’t understand the waves. Later, you learn to see patterns and you learn to see flow, you learn to be in the right place at the right time.

For architect Craig Steely, knowing when to engage with new clients requires the ability to see patterns and flow, similar to knowing how to surf. "Surfing is about proportion, flow, and perfecting line," he says.

It’s like being in a marketplace where everyone speaks a foreign language. At first it all sounds incomprehensible. But then you learn to perceive the cadence of speech, to see rules in the chaos. The client interview process is similar: over time, and with experience, you learn to trust your instincts.

How do you know when to tear down and when to preserve on a remodeling project?

It’s driven by the client and by the situation. You don’t want to end up with a facade that’s a parody of what it was. If a client wanted to preserve something that I didn’t feel was warranted, I’d send the client to another designer. But I like some of those really massive Victorians with the huge interior spaces. I’d like to try something with objects inside of that big envelope.

Doug Shoemaker

14. Dec, 2011

Rebecca:

Great article and well written about Craig. I admire his work so much and his process and ethics.

As a sole practitioner architect I know how hard it is to do this kind of great work. thanks.

Doug S.