Alan Tse: Adaptive Modernism

by Rebecca Firestone with Mark English AIA | Interviews

“My first valuable opportunity for a signature 11-story high-rise condominium building was shattered by all 7 Planning Commissioners… 672 hours later, I transformed from a egotistic architectural designer into a humble-minded individual getting a career-long lesson.”

(Image courtesy Alan Tse)

Mark English and I met with designer Alan Tse at Nabe Restaurant in the San Francisco Marina, one of his projects. Nabe has two locations, both designed by Alan. “Nabe was designed as a communal dining experience,” he explained. “One long table, with hot pots in the middle. Nabemono (Japanese hot pot cuisine) is a very traditional, Japanese family-style way of eating. Yes, it’s loud in here, especially on a Saturday night.”

Alan had arranged for us to have a special catered lunch there on the restaurant’s off hours – a gesture of hospitality that was in keeping both with the restaurant’s theme and his own personal ethos. “I try to focus on the client, rather than on myself. I learned to be adaptable, to read people’s faces, and think about their needs before they do.”

Nabe Restaurant at one of its locations, at 2151 Lombard Street in San Francisco, referred to in Alan’s materials as Nabe II. This is where we ate when we spoke with Alan. The Japanese panels create a small sense of privacy without interfering with the flow of the space. A communal dining experience. The food here was excellent. Photo courtesy Alan Tse

- Nabe’s other location, in the Sunset, also referred to as Nabe I. “Nabe I was an interior remodel of a ground floor office space into a Japanese hot pot restaurant. This project embraces the communal dining experience of nabemono and replicates the visions of street food vendors found in the alleyways of Japan. The enclosure of the space is muted with steel panels and plaster finished walls, housing a communal table within a hickory wood construct. Architecturally, it is a box within a box.” Photo courtesy Alan Tse

- Alan Tse improvised the artwork in Nabe I using wine boxes. He stenciled the writing on it, added sake bottles, and put spigots beneath. Customer could “sign” each bottle. “This Wooden Box wall was our re-interpretation of the Polaroid photo wall of regular customers, that we still see in other neighborhood restaurants.” Photo: Alan Tse

- Another view of the table and interior in Nabe 2. He’s created an enclosure for the central table. “After one successful project, the client was willing to invest more in the buildout budget. And from the success of the first location, I was more confident in proposing a more daring design.” Photo courtesy Alan Tse

Business Strategist

One way Alan Tse serves his clients is as a business strategist. For restaurant owners, the first few conversations are purely about timelines. Alan guides them in doing critical things at the right time: when to sign a lease, when entitlements have to be completed, when to have their finances lined up. “It does no good to call me every day asking about the permit. That’s my job. You as a client should be spending that time getting your finances in order.”

In addition to lining up finances, the client should be developing their business model. “My belief is that the architectural design must synchronize with the business model from the beginning.”

“Nom Burger is a tenant improvement of a ground-floor commercial space within a newly constructed, mixed-use building in Sunnyvale, CA. All ingredients are made in-house, including the buns, meat patties and unique toppings. The various design elements and their detailing embrace the same craft as the menu, without any generic, digital technology.” Photo courtesy Alan Tse

Alan actually doesn’t even talk about design for the first two conversations with a new client. “As designers, we need to act responsibly and point out the challenges in each project. We have to allow the client to understand the project they are about to commit to, and all parameters that may affect the outcome of the project. Don’t start with a fancy design vision that has not yet determined to be feasible.”

“Try to learn from past mistakes,” he advises. “I really try to help new clients to avoid problems I’ve encountered in the past.” A client should know how to take direction from someone with more experience in that area. Some of those mistakes were his own: one of his first multifamily projects in San Francisco had to be redesigned in under 2 weeks in response to planning comments.

Counter at Nom Burger. Somehow one expects the food to match the qualities of the decor… simple yet very high in quality, thoughtfully executed. Photo courtesy Alan Tse

“672 hours later, I transformed from a egotistic architectural designer who was hungry for his first signature high-rise into a humble-minded individual getting a career-long lesson on how to properly design a building and practice in the Architecture profession.”

In residential housing, his approach to one client showed the same level of care. “This client is a guy with two young kids, who works at a major technology company. I first asked him what his actual occupation was – he’s a quality assurance engineer for high-end consumer hardware devices. So I knew he’d appreciate minimalist, Modern forms.” Apart from acknowledging a preference for Modern design, this client approached Alan after seeing his work in San Francisco. He found Alan’s work refreshing after the typical residential architecture normally encountered in the South Bay.

“I also have to think about the client’s own future,” he went on. “This client had bought land in a suburb on the Peninsula, probably paying $1.5M for it. Steering him into a $20M dollar tech mansion is not going to serve him in the future, not with 2 young kids and a family to raise.”

Another proposed housing project. This image presents a sense of quiet mystery and calm. The volumes are offset for interest, and the front facade has both symmetry and a sense of rhythm. Image: Alan Tse

Offset House

Alan Tse refers to this particular project as the “Offset House”. It’s a single family home on the Peninsula, between San Francisco and San Jose in California. Bisected down the middle, and top to bottom, Alan created a composition that keeps a sense of simplicity with an intriguing center of interest: what isn’t there is as important as what is. “I sacrificed floor-to-ceiling windows to get this cantilever.”

“The Offset House is a new construction of a single family home in Cupertino. This simplistic form is a result of an offset detail between the two stories. This idea of an offset carries through the form of the building, including the interior layout, the organization of the various programs, and interior finishes.” Image: Alan Tse

“Forget that $20M project. For my suburban client, should I even propose a $5M budget? No. Instead, I scaled the project to the construction budget, to get more project, and a better design, out of that smaller budget.” Part of the design included conversations with the structural engineer about the offset framing and roof curb, as well as ensuring that the contractor has enough guidance to get the offset right during construction. “We had to keep the project within feasible means with regard to the land cost, and create an optimal budget, in order to make this project more attractive to the wave of incoming tech industries buying up the neighborhood.”

Visual communication with the client should create a sense of place. In this new Market Street multifamily housing proposal, Alan carefully chose the rendering point of view to emphasize the custom-designed steel and glass door, and to create a sense of perspective and depth. Image: Alan Tse

Right-sizing his projects is good for his business, too. “In the Offset House neighborhood, very few people use architects. When they do… the designs are very repetitious. This project could open up other opportunities with other clients of this same income level – using the same conventional building systems, the same finish materials, and following the same zoning guidelines.”

Alan spoke about designing for a smoother permitting process. “A guy with young kids shouldn’t have to wait 3 years for entitlements, because of an overly daring design. “That town has a by-rights permitting process. If you stay within the rules for things like setbacks, it speeds up approvals, reduces risk, and tailors the project to the clients’ own circumstances.” He and Mark English discussed the strategic pros and cons of adding and subtracting a basement during the permitting process.

The Offset House exterior uses ordinary materials, painted siding and stucco. “You don’t need an all-glass box or a fancy building skin to be attractive. This is about what is achievable. It’s not paper architecture that is hard to materialize.”

Alan does his own lighting design. In his renders, light color makes a huge difference in effect. The bluish light in the background could be from a north facing daylight window. Image: Alan Tse

Client Relations

Alan is very direct with clients. For residential clients, the first conversation is about their background and their stage in life. Then he tells them what their budget should be, and, at times, he has told clients “You should not be doing this project.” Not “I can’t work with you” or “You should find another designer,” or “Your ideas of budget are unrealistically low,” which is the more usual way of turning down work, or firing a client.

Sakesan Restaurant in San Francisco. Alan made all these panels himself. “I had one guy and a hammer.” That’s called “sweat equity” and it helped keep project costs down – thus allowing that budget to be spent elsewhere, on making other details better. Photo courtesy Alan Tse

Alan also insists that his clients have a clear concept, a plan. This may depend on the type of project. For a family restaurant, it’s not enough to pick a cuisine. There are thousands of nondescript eateries out there already. For a multifamily housing project, branding is important. “For La Maison, I didn’t think of it as a monolithic, 28-unit building. I thought of it as 28 homes.” For residential clients, a concept includes what they want to do with their lives.

A minimalist Japanese aesthetic also allows for rusticity at Sakesan. The Wiki entry for the Japanese word “Shibui” includes “a particular aesthetic of simple, subtle, and unobtrusive beauty … enriched, subdued appearance … subtle details, such as textures … one does not tire of a shibui object but constantly finds new meanings and enriched beauty that cause its aesthetic value to grow over the years.” Photo courtesy Alan Tse

Single-family residential architects often start with a client’s program. What do you want to do in your home? they ask. How do you want to live? The smart ones ask all the family members, including the kids. A common error is to address the male partner and ignore his wife… which can lead to divorce between architect and client. Some of these designers, like interior designer Gary Hutton, actually observe their clients at home or hanging out on various pieces of furniture, watching their body language, seeing how they like to relax.

Once more, Alan Tse is thinking three steps ahead. “Living in a house with one kid is very different from living in a house with three kids,” he noted. “Don’t be a dictator on how a client should live in their own home. Recognize what the homeowner wants. On budget allocations, I’ll make three tries for those floor-to-ceiling Fleetwood windows. After that, I back off.”

What if someone asked you how to be a good client? I asked. “Have boundaries. Respect your design professional. Don’t second-guess them all the time, or breathe down their neck about a permit when you should be getting your finances in order,” Alan replied. He was talking here about restaurant owners, since restaurants are often family-owned businesses.

Visual Communication Skills

Another building floating in space, image becomes art. In fact, this image would look great in a museum on a 15-foot canvas. The window reflections actually appear to be painted onto the ceilings and walls of the interior rooms. That may not have been the intended effect, but I’d actually love it if they did that for real. You would never guess that this is proposed hotel and dental clinic at 900 Clement Street in San Francisco. Image: Alan Tse

Architects have to be able to sell their design vision: to clients, to city planners, to the neighborhood approval committees. Alan had some interesting things to say about communication. He seems highly people-centered, and puts the desires of his clients far above his own ego. “I watch people’s faces.” The other thing he emphasizes is visual communication through renderings, drawings, physical models, and other tangible methods that ordinary people can relate to directly.

“The 900 Clement Street project includes a dental clinic with 12 dental stations and 8,313 sq. ft. of new construction. The design challenges the expected clinical setting by adding atmospheric features of day spas, and abstraction of various water elements.” Image: Alan Tse

His teaching side comes out with office interns as well as in his studio classes. Interns are encouraged to apply for design competitions, which they then manage themselves. The other thing they have to do is create physical models from construction drawings. No cheating by looking at the CAD files on a computer. “Interns learn to understand the relationship between those drawings on paper, and what they represent. They have to convey the design intention to people in the field who will be building that project.”

“Learn to be more thoughtful in how to convey information to other people.”

- A collection of little model boxes, lined up like Legos. Image: Alan Tse

- Alan carefully stacking those little model boxes. Image: Alan Tse

- Same little model boxes on their sides, in another formation. Image: Alan Tse

Developing a Design Process

Why should you become architect? Mark asked. “From high school onwards, I was very interested in digital design, and computers,” Alan replied. “I’d tried to get into UCLA, but ended up at UC Berkeley instead. The only way at that time to do computer design was in the architecture program. I didn’t warm up to architecture right away, until my second studio class.”

“Before that, I was a bad straight-A student. I did exactly what I was told. If someone asked me to make a model, I would ask how many, but I never asked why. I didn’t understand what design meant until I took Lisa Iwamoto’s studio class.” Professor Iwamoto wouldn’t look at his detailed, carefully crafted drawings. “She kept her teaching at a partí scale, design as a concept or a glyph.”

Finally at 2am a light bulb went on. “I finally understood the starting point for design.”

This project’s still in permitting so it must be a render. You have to squint really hard to tell that, though. Aside from that, the facade is a lot more interesting than a sterile expanse of flatness. Image: Alan Tse

Alan trained with Stanley Saitowitz his last year at college, and ended up working in Saitowitz’ studio all through graduate school. “Stanley runs a very efficient practice that can take on any quantity of work wit the same staff throughout the years.” People know what to do and don’t need excessive amounts of supervision. A lot of architectural firms have to determine their optimal size, number of employees, and adapt a suitable management style. It’s a lot simpler to do the work yourself if you can. The next best thing is having people you can count on to work independently.

The next critical point in Alan Tse’s development as a designer came while working in Saitowitz’ office. “Stanley taught me how to design: what is good design and bad design, what we should and should not do. Mainly I learned by watching.”

He was there when Saitowitz did his first sketch for the Beth Sholom Synagogue, with its inverted bowl-shaped form. “I would secretly watch from the printing loft above the office and see my boss in the act of design, his process.” Saitowitz didn’t waste much time on verbal instruction.

Temple Beth Sholom, one of Stanley Saitowitz’ designs. Alan was there when the first napkin sketch was drawn. The whole form is spellbinding as a magician’s trick, a visual illusion, where the “bowl” seems as delicately balanced as a rock on a cliff’s edge. Image: Stanley Saitowitz | Natoma Architects

A third critical point came after Alan had been working with Saitowitz for 4 years, and wondered, “Is this method the only way to design?” A desire for exposure to other design approaches ultimately led back to graduate school. “I got very emotional during a critique where my design approach was questioned. I faced a choice: to become a disciple, or to develop something I could claim ownership of. Ultimately, I embraced Stanley’s design aesthetics but evolved my own design methods and philosophies.”

The two years of grad school gave Alan an appreciation of different types of architecture. “This is what ultimately enabled me to become a teacher,” he told us. “I’m still in Stanley’s office. When I’m there, it’s my responsibility to perform for my employer, and to carry out his creative vision as best I can.”

What Else He Learned From Stanley Saitowitz

Mark English and Alan both agreed that Stanley Saitowitz possesses extraordinary powers of persuasion. He was a sort of “Planning Whisperer” who could convince planning boards to accept his ultra-Modern designs in a city that is still to this day in love with Victorians, and staunchly anti-development. “It was his personal charisma.”

Another thing Alan learned from Saitowitz was how to present and render projects, how to communicate a vision, and ultimately how to persuade other people to believe that vision. “Stanley thought like an architectural photographer. His designs were informed by the camera angle from which it would eventually be photographed.” Alan taught himself how to create computer renderings, back when renderings were an exotic technology that only a few people knew how to do.

Once again, facade with broken-up volumes for interest and complex rhythm. Window louvers and the ground-floor facade create additional texture. Image: Alan Tse

“Renderings help me communicate design intent to a client who may not be proficient at reading architectural drawings,” he said. “I also do my own lighting designs, and renders help me to envision how it will look, how the space will feel.” Clients often care more about interiors, whereas city planners care about the building’s relationship with the neighborhood context.

A proposed 7-condominium building on Franklin Street, with each unit taking up an entire floor. Image: Alan Tse

Architect as Problem Solver

Working with contractors can be challenging for a designer fresh out of school. “These guys are a lot older and more experienced than I am,” he explained. “To earn their respect, I have to be able to answer their questions right away, on the spot, by reviewing their construction drawings in the field. I can’t dig things up on my laptop and try to figure it out.”

“Be definitive. In the field, you have to be able to point at stuff and explain the design intent, why the glass is here and not 2 inches over. Sometimes, I turn it around and ask the contractor, So what do YOU think? and listen to them first.” Alan spends a lot of time visiting projects in construction.

Independence was important in the office as well. On one Saitowitz project, the Hotel W, the scope increased dramatically from 3,000 square feet to 20,000 feet. “It was a lot of responsibility for a young designer. The contractor was calling me up asking about the roof drains. I had to make a decision on the spot. I couldn’t go running to Stanley all the time. I had to own it myself. That’s what was expected of me.”

The Hotel W was an interior remodel project done with Stanley Saitowitz. The project increased in scope from 3,000 sf to 30,000 sf, and included a guest lobby, commercial kitchen, 2 full bar + dining areas, and 3 additional lounge areas. Image: Alan Tse

- Hotel W facade, looking upwards. Image: Alan Tse

- Hotel W interior lobby. Image: Alan Tse

Did you check with Saitowitz afterwards? “No… not most of the time, anyway. Maybe it wouldn’t have been exactly how he would have done it. On the other hand, he didn’t have to be bothered.” Decisiveness and ownership make for valued employees in many industries. Management also needs to trust their employees and not micro-manage them. “Employers want people who are problem solvers. Many junior architects do not understand this.”

Travel

We asked Alan about travel as a broadener of experience. “I pay attention to context. Context informs who you’re designing for. For example, when traveling in Japan to visit my wife’s family in the wintertime, there’s a certain smell. It’s a combination of charcoal filtering in the heaters and the tatami mats. You have to be sensitive to those memories as sensory triggers, and incorporate them into your design strategies.”

“I paid close attention to the bathing practices in traditional Japanese homes. How do they keep the water in the soaking tub warm for an entire week? Turns out the water is insulated by a tatami mat covering the tub. How can one family share the same tub of water for a week? They shower first!”

Buildings as Concept Car

What’s your favorite building? we asked. “Best Buy. It’s got pragmatic design and efficiency within close parameters. I’m always teaching my students about how to create purposeful design, and Best Buy is very successful at its intention.”

He had more to say about his favorite cars. “I like sports cars, always have. But my favorite car might be the Porsche 911. It’s the evolution of many geometries, many features, over the years. It’s a belief that they will continue to fine-tune the original product, correcting flaws, optimizing features.”

The La Maison project is kind of like a concept car, he said. Why? “The developers have been working in San Francisco for 40 years. They started out building stucco boxes. For them to achieve THIS result, I’m proud of that. I’m proud for them. I’m proud of their skill set, proud of our working relationship, and proud of the fact that they believe in my vision now. That took a lot of effort, by the way,” he laughed.

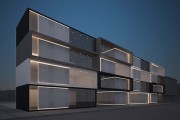

La Maison is a new 28-unit condominium building in SOMA district of San Francisco. “The design is an architectural composition of 28 urban homes in a live/work loft aesthetic that is familiar to this area. While each home shifts and projects in both axes, the composition as a whole results in a highly articulated facade and form.” Photo: Bruce Damonte

- Treating a multifamily housing project like a concept car, and unveiling it creates a dramatic showing to the client. The white scrawl at the bottom of the veil is actually Alan’s signature, borrowing the tradition from high-end car manufacturers etching the autograph on the engine from the technician who built it. Image: Alan Tse

- Alan Tse had to talk the developers of La Maison into giving up a small amount of floorspace in order to get an 8-inch offset. Image: Alan Tse

- Branding is as important as every other aspect of Alan Tse’s designs. Image: Alan Tse

Alan had to talk the developer into staggering these 28 homes to create a less monolithic facade. This 8-inch overhang cost them a tiny amount of floorspace. In formula-based design, floorspace is priced per square foot, and any reduction in floor space represents a reduction in profits. “That 8 inches took away 1% of the floor space. I had to do 3 sets of budget analyses for them in order to prove that my idea had value.”

Even the width of the units themselves, 25 feet, or slightly larger than the standard San Francisco size lot, was a strategic decision. “It helped the building blend into its context, which was a good argument for Planning.”

Cost Efficiency and Results

The Sakesan restaurant was one of the projects he showed during his talk at the Monterey Design Conference. Everyone wanted to know how he did it for only $60K. Most architects think that you can’t do a restaurant with a full commercial kitchen for under $75K. Shizen, another restaurant project, also makes maximum use of minimally worked natural materials.

Shizen Restauarant is another minimalist intervention in an otherwise unadorned interior space. Photo courtesy Alan Tse

- These simple boards form a tunnel, or enclosure – an open cage that interests without confining the viewer within. Photo courtesy Alan Tse

- The long perspective creates a contemplative, restful effect, that might partially offset the liveliness that this place probably has when it’s filled with diners. Photo courtesy Alan Tse

- The simple boards create an interplay of light and shadow. Photo courtesy Alan Tse

This led to a discussion of tools. What did he think about parametric designs? Computer-aided stuff? Was it too clever? Shouldn’t people just make it themselves, by hand? And was that cheaper than a lot of CNC routing for, say, the Sakesan restaurant? “It’s not the tool but the result,” he said. “Use what you have available to you.”

Broadening His Service Offerings

Although many designers extend their activities beyond the building to include interiors, lighting, landscaping, furniture, and graphic design, Alan has several differentiators: strategy, diversity, and branding. Branding for La Maison included a rendering that made the building like a concept car, with unveiling. “It’s not 28 units, it’s 28 homes”.

Strategy is tailored to the project type. For a single-family home, the strategy might include design decisions to keep the project on track and keep the client from over-spending. Getting a better designed home that is right-sized is far preferable to chasing after an overly ambitious design. For developers of multifamily housing, the strategy might include shaping the experience of the buyers. Selling “homes” rather than “units” or promoting an image that inspires trust in the developer and, ultimately, in the habitation itself.

Different renders serve different purposes. Planning departments care about context, while clients care about the bathroom. The designer can use various renders to direct the discussion.

For restaurant owners, Alan has a very clear idea of timelines to help the owners stay solvent and on track. How much client grief could be avoided by knowing upfront what’s really important, and how much they’ll really have to spend? Presenting an attractive business plan, including branding, to a lending institution or investor can help the client with securing financing as well. Effective renderings can help the client to create a more convincing business plan.

Alan seems to be able to push things through planning and approvals with great effectiveness – through strategic design choices and carefully tailored presentations. An overly ambitious design that breaks all the rules and requires any sort of discretionary review can drag on for years, costing clients time and money.

In some ways these renders are standalone art compositions. This building looks like a high-end fortress on Mars, isolated in desert silence. In reality it’d be in an urban environment, of course, and the mystery would be experienced within. This design is for Arsenal, a proposed American cuisine restaurant. Image: Alan Tse

- A good render creating a mysterious, dark, moody feeling. Image: Alan Tse

- This render creates a strong sense of place. Good for playing with lighting designs. Image: Alan Tse

- Although the render makes this place feel quiet and hushed, my guess is that the hard surfaces would give a bright, loud acoustic, while the low lighting might help reduce over-stimulation. Image: Alan Tse

Goals

“I want to work my way up, rather than being a ‘society architect’ stuck doing one type of project: only modern mansions, or only restaurants. I want a diversity of project types, in order to make myself adaptable.” He works hard, too. One proof of that is the speed with which he provided numerous images and project descriptions for this article.

I asked whether architects had to mimic their clients’ lifestyles, whether they should conduct themselves as social equals or as respectful inferiors – of a special breed. “Some architects work in the realm of the ultra-wealthy. They’re hobby architects, and may be independently wealthy themselves. They think it’s somehow dirty to promote themselves. There’s a myth I’d like to dispel, the myth that it’s somehow shameful to be successful as an architect. I totally disagree with that! People should discover how great you are.”

His message: “It’s good to think strategically in order to achieve good designs. You don’t have to be independently wealthy to build a career in architecture. You’ll learn more if you start from the bottom.”

We shot this candid photo of Alan Tse at Nabe Restaurant during our interview. Image: Mark English Architects

Links

- Alan Tse Design web site

- Nabemono, meaning of

- Gary Hutton Design (interior designer)

- Gary Hutton featured on The Architects’ Take, Part 1 and Part 2

- Beth Sholom, by Stanley Saitowitz | Natoma Architects, San Francisco, 2008, in Archdaily

- Architectural Record interview with Alan Tse, 2017

- Alan Tse’s writeup of the Offset House

- Alan Tse’s cliffhanger on his first permitting debacle, transformed into success. Most people turn wine into water, but Alan Tse turns water into wine!

- Alan Tse Design Vanguard interview