Sao Paulo, Brazil: Modern Buildings and Climate

by Rebecca Firestone with Mark English AIA | Editorials

In countries where energy costs are high, buildings rely less on high-tech conditioning and more on simple features such as brise soleil to create natural shade. The Modernist gems of Sao Paulo show how climate response can be both inspirational and livable. Image: Ciccillo Matarazzo pavilion, Mark English Architects

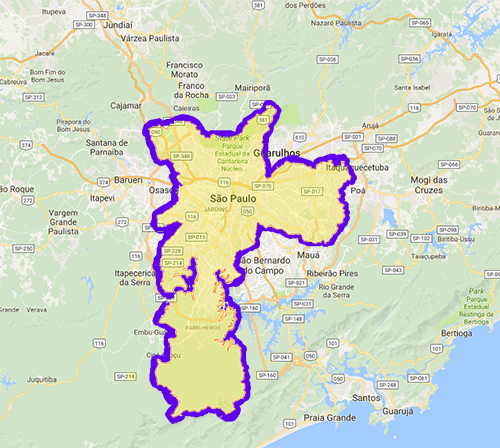

Sao Paulo, Brazil — the most populous city in Brazil, a mecca of commerce, finance, arts and entertainment… described by Lonely Planet as a “monster” that still possesses a “fertile cultural life”, a multicultural melting pot of 20 million people in an area of 576 square miles. And, boasting a major collection of Modernist art and architecture with a uniquely engaging spirit.

What did you like so much about it? I asked Mark English, as he showed photo after photo: bus stops, high-rises, museums, storefronts. “In a real way, the buildings respond to climate,” he answered. “They’re inspirational, yet easy to live with, in a way that people of all different backgrounds can appreciate. You don’t need a degree in art history to understand them. By contrast, New York City can seem oppressively self-referential.”

Similar landmarks in other cities are not so accessible to the untrained mind, apparently. “In Brazil, I wanted to focus on what can be learned from these buildings, in order to employ the same techniques in my own projects.” He mentioned several features, one of which was brise soleil – also seen in Desert Modern architecture from the 40s and 50s.

What Is Brise Soleil?

In its most literal sense, the French phrase “brise soleil” means “sun breaker”, or something that breaks up sunlight. The all-knowing Google defines it as “a device, such as a perforated screen or louvers, for shutting out direct or excessive sunlight,” i.e., a sun shade. This feature reduces solar heat gain while still allowing free air circulation.

Armando de Arruda Pereira Pavilion, also known as Oscar Niemeyer’s Prodam Building, located in Ibirapuera Park in Sao Paulo, Brazil. This building fell into disrepair for a while, but is now being refurbished. Image: Mark English Architects

Principles of Sun Shading

To be effective, brise soleil should be applied on the South or West side of a building in the northern hemisphere – or on the North side for buildings in the southern hemisphere. It also works in equatorial regions. Shading methods include both vertical fins and large overhangs. By blocking the sun before it strikes the wall or window, sun shading is far more effective at managing heat gain than even the most reflective of glass, or interior shades. It reduces glare in areas with very bright and direct sunlight, making them feel more livable and less exposed without compromising outdoor views.

The louvered example below, a museum in Sao Paulo, shows both effective brise soleil, as well as another principle expressed in many of these Brazilian buildings: a practical emphasis on mechanical simplicity.

Bienal Pavilion, by Oscar Niemeyer and Helio Uchoa, built 1951, located in Ibirapuera Park, Sao Paulo, Brazil.These simple operable louvers allow control over the amount of direct sunlight that reaches the building itself. Image: Mark English Architects

From the inside, it is easier to envision how the sun’s arc across the sky results in changing amounts of shadows or sunlight at different times of day. Image: Mark English Architects

A simple mechanical louver doesn’t need complicated software or motors to be effective. Image: Mark English Architects

Brise Soleil Pioneers

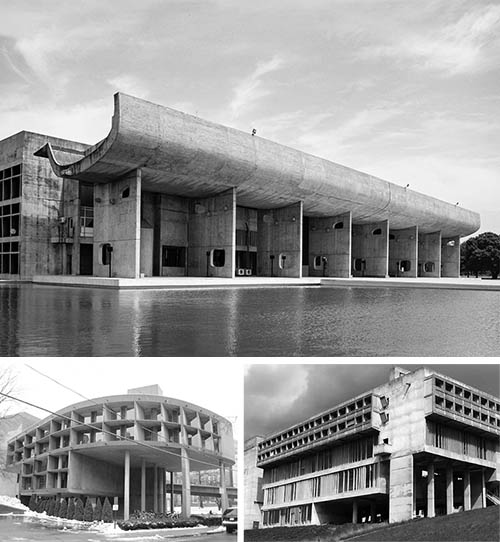

Although air-permeable perforated screens that reduce direct sunlight have been around for millennia, the brise soleil concept specifically refers to blocking the sun’s rays altogether through careful positioning of horizontal or vertical fins, at an angle that is sometimes adjustable and sometimes fixed in place. One pioneer of this approach was le Corbusier, who employed sun shading in many of his projects, including well-known works such as Chandigarh, La Tourette, and the Carpenter Center.

Modernist architect Le Corbusier pioneered the use of brise soleil in the earlier part of the 20th century. Shown clockwise from top: Palace of Assembly, Chandigarh, India, built 1962; Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, Cambridge, MA, built 1963; Sainte Marie de La Tourette monastery in France, completed 1960. Note the deeply set windows, sheltered bottom story, and vertical fins.

When divorced from its original purpose, this same feature elsewhere has become what the Modernists used to call “useless ornament”. For example, too-small fins on the north or east, or shading that is not correctly sized for the latitude and angles of the sun, can cause this feature to lose all connection to its original purpose.

Horizontal fins look similar to vertical louvers, but they don’t prevent the sun’s rays from striking the window glass, and thus the original function they might have served is lost. This feature may work better on the South facade (facing the viewer) than on the West (left). City College of San Francsico campus.

“Another granddaddy of brise soleil was Louis Kahn,” says Mark English. “At the Assembly Building in Dhaka, he encased the whole building inside a shell, to protect it from the tropical sun.”

Oscar Niemeyer’s Copan Building

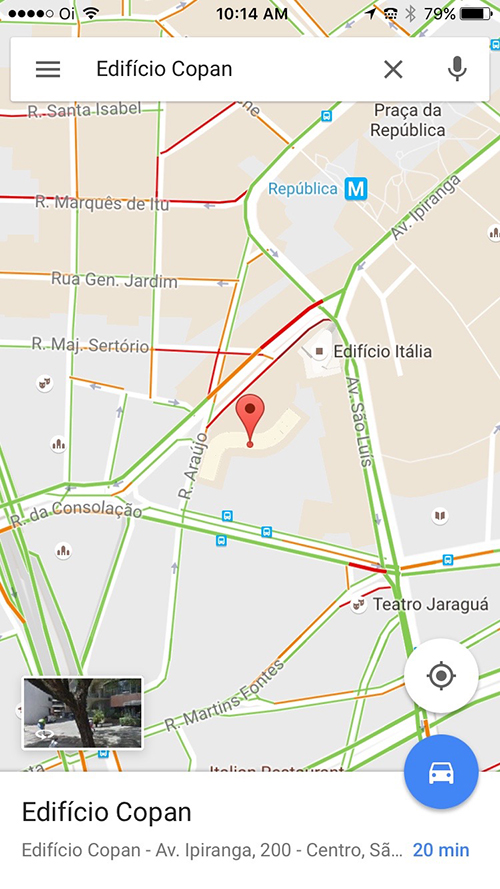

Another interesting example of Brazilian Modernism is the Edificio Copan by Oscar Niemeyer, built in 1961. Sao Paulo boasts several works by Niemeyer, with Copan being one of the largest. With 1,000 residential units, it’s so big it has its own postal code. It is currently being remodeled after falling into disrepair.

Oscar Niemeyer’s Edificio Copan (Copan Building) in Sao Paulo, Brazil, boasts a distinctive yet simple “s” curve, and has 1,000 residential units.

Oscar Niemeyer’s Edificio Copan is located in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Coverings are from recent construction. Image: Mark English Architects.

Generous overhangs Oscar Niemeyer’s Edificio Copan shades pedestrians at the ground level. Below the building itself is an internal “street”, an underground shopping area. Image: Mark English Architects

Oscar Niemeyer’s Edificio Copan. A 2-story restaurant nestles under the eaves. Image: Mark English Architects

Mark English explains his affinity for this particular building. “It’s super-tall, simple, strong, and modern… timeless, consisting of one smooth, sweeping sensual curve. It expresses an optimistic vision. It is not based on a compositional exercise, or abstract geometries, like works by Hadid or Liebeskind. This is about creating an experience.”

Mario Kagan’s Vitacon Itaim Building

So, people were using brise soleil in the 1960s, what about today? Here are some sliding wooden screens on two sides of a corner high-rise by architect Mario Kogan at Studio MK27, also in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Vitacon Itaim was completed in 2014.

Marcio Kogan’s Vitacon Itaim building uses sliding wooden screens to control sunlight. On the right side, the screens unfold to cover the window surface. On the left, there is a single, moveable wooden screen. Image: Mark English Architects

This close-up shows the perforated wooden screens on Marcio Kogan’s recently completed Vitacon Itaim project, in Sao Paulo, Brazil. From image by Pedro Vannucchi

Stanley Saitowitz and Brise Soleil in San Francisco

A recent article on The Architects’ Take featured the work of Stanley Saitowitz among others. Mark English emphasized Saitowitz’ creative problem-solving and mentioned several other Saitowitz projects.

Stanley Saitowitz’ 8 Octavia project uses the same louvers as were popular in the 50s, a simple and elegant solution to controlling how much sunlight reaches the building interior. Image courtesy of DDG

Stanley Saitowitz uses a form of brise soleil on his project 616 20th Street in San Francisco. (The reader can view the project photos on Natoma Architects’ web site and decide if it works or not.)

On this visualization of a new project at 2740 McAllister in San Francisco, Stanley Saitowitz uses generous overhangs, recessed window walls, and vertical side fins to allow a mix of shade and sun.

Conclusion

Sao Paulo and other Brazilian cities can teach us a lot about efficient building design, as well as having an aesthetic that celebrates a sensual experience rather than a purely intellectual one. Many of these treasures are under-appreciated by those who live in other parts of the world. Look for further articles on Brazilian modernism.