New Orleans Rebuilding: Could Topography Make It Right?

by Rebecca Firestone with Mark English AIA | Editorials

A Tulane University geographer reframes the debate about the fate of below-sea-level New Orleans. “The city still has over 2,000 open lots all above sea level – a precious natural resource whose use we should prioritize for human occupancy. Filling in these pockets would also help mend the urban fabric that was torn by the population exodus ongoing since the 1960s. And we can do this without marginalizing low-lying neighborhoods.”

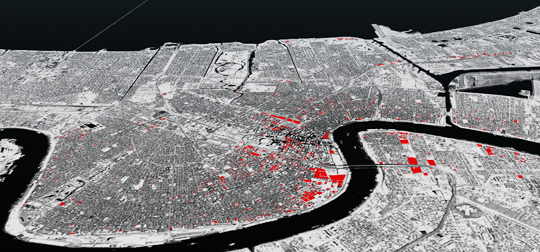

(Map courtesy Prof. Richard Campanella)

A year ago, we published an editorial critique of some of the post-Katrina rebuilding efforts in New Orlean’s Lower 9th Ward, specifically those of the Make It Right! organization. We questioned the vanity of celebrity philanthropy: why build only a few hundred expensive LEED homes when far more homes could have been rebuilt for the same cost?

During the course of writing that piece, we came across a viewpoint even more contrarian than ours: geographer Richard Campanella of the Tulane School of Architecture. Campanella has spent the past 17 years researching New Orleans’ historical geography, authoring six books and numerous papers on the subject. He pointed out that large portions of New Orleans are on reclaimed swampland that were probably best left undrained and undeveloped.

“If you build sustainable structures but place them in a geographically unsustainable site, have you really ‘made it right’?… I personally identified over 2000 open parcels of above-sea-level land in the heart of the New Orleans historic district. That’s where MIR should have built.” (The map shown at the top of this article indicates the above-sea-level areas in green – paradoxically, they’re the ones closest to the Mississippi River, because in a deltaic environment, rivers deposit sediment along their banks.)

Campanella had actually published a study in 2007 titled “Above-Sea-Level New Orleans: The Residential Capacity of Orleans Parish’s Higher Ground” explaining how he found these open land parcels, and evaluating how many people could be resettled there at various densities.

Geographer Richard Campanella, a professor at the Tulane School of Architecture, has identified over 2000 parcels of open land above sea level within the City of New Orleans that could be used to build safer and more sustainable new housing for people displaced by the flooding caused by Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Image courtesy Richard Campanella.

Hurricane Katrina in 2005 was only one of many forces shaping change in the City over the past three centuries since it was first established, and the population had been declining from its 1960 peak of 627,000 people. Major civil engineering projects that originally enabled settlement of low-lying areas in the early 1900s were also to blame for subsequent environmental deterioration, namely the sinking of the soil by six to twelve feet below sea level and the introduction of gulf waters to within city limits. Regional navigational canals, meanwhile, accelerated the erosion of sediment-starved coastal wetlands, which allowed hurricane-induced storm surge to incur father inland and exert pressure on what proved to be under-engineered federal flood walls and levees. When those systems failed to impede Hurricane Katrina’s surge in August 2005, it was those twentieth-century below-sea-level subdivisions that suffered the deepest flooding.

How has that report been received by governing agencies and the media?

It landed on the front page of the New Orleans Times-Picayune. That article was mostly dedicated to my observation that half the city is above sea level, but my original report went much farther than that simple fact. That fact by itself didn’t have any policy impact. And for good reason – the question whether the City should move people to areas above sea level played out after Katrina as what I’ve dubbed “the great footprint debate:” should New Orleans close down those low-lying areas? That’s where the trouble started. Suggesting that some residents would not have the “right to return” to their homes proved very bitter and contentious.

Eventually authorities settled on the only thing that seemed workable: all neighborhoods would come back; no areas would be officially shut down, no matter how low-lying, far-flung, risky, or depopulated. They really had little choice. There was no pool of cash with which to compensate homeowners quickly and fairly, so flood victims naturally gravitated back to the one thing they still owned: their land and wrecked homes. The city’s ultimate resolution was simply to let people return as they wished to where they wished, and to act passively on those patterns as they fell in place. They essentially decided to not decide. For better or worse, it was a failure of urban planning, and a triumph of decentralized citizen-level activism. This all played out in late 2005 and early 2006.

New Orleans boasts a wide variety of historical architectural styles. Both these homes are located on Freret Street, which is currently undergoing a renaissance following the disaster of Hurricane Katrina. Images from recent property listings on Zillow.

My study, which I conducted after the great footprint debate played out, wouldn’t change any of that. The purpose was to point out that, by the way, we have a resource on higher ground, that we can use without closing down any other neighborhoods. I wanted to change the terms of the debate away from the negative couching of closing down below-sea-level areas, and toward the positive approach of making the absolute best use of above-sea-level areas.

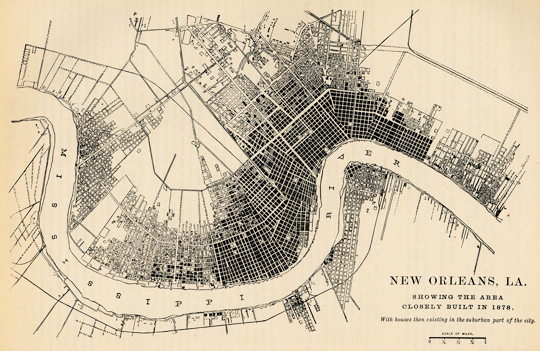

A hundred years ago, New Orleans’ population was around 300,000. Today, it’s not that different – 356,000 people. The difference is, the City in the early 1900s had a much smaller footprint, and nearly all of it all above sea level. The major civil works projects that drained the low-lying swamplands hadn’t yet been undertaken. Of course, more has changed than just the topography. People today expect more living space and wouldn’t necessarily be willing to live at turn-of-the-century urban densities. Still, even with that in mind, New Orleans still has over 2,000 open lots all above sea level that people could occupy and gain a topographic advantage.

Being above sea level does not make you immune to all flooding. If you are unfortunate enough to live in a hydrological sub-basin that suffers a levee breach, you may flood even if you live above sea level. But the depth will be less, probably dramatically. Topographic elevation is an absolute good in a deltaic city. Living on higher ground is the one variable you can control. You cannot control the weather or the wetlands or where the levee may fail, but you can arrange your space to lay above where the water level may settle.

Could people live on those lots today if they wanted to?

In my research, I was looking for open, grassy lots or lots that were very “lightly used”. Not all of these are zoned for residential use, however. So the first thing would be to re-zone some of those parcels to make it possible for people to live on them. At the present time, these lots are ones that could, theoretically, be converted to residential land use. In the newspaper article, you’ll notice that there’s only a small-scale oblique map of these parcels. That’s by design. We didn’t want to get angry calls from landowners who thought we might be trying to take their land away from them.

So, that report is not a policy blueprint. It’s a way to gently suggest that we have a scarce and valuable natural resource here, and it may not be currently put to the best public use. These lots are almost entirely in historic neighborhoods that were settled prior to the turn-of-the-century drainage operations; the infrastructure to support a high population density is already in place. Filling in these pockets would help to mend the urban fabric that was torn by the population exodus that has been ongoing since the 1960s. And, we can do this without marginalizing low-lying neighborhoods or shutting anyone out. No one needs to move if they don’t want to.

In 1878, New Orleans had a substantial population not that much below what it is today, all of it settled above sea level. Image courtesy of Richard Campanella, originally from “Report on the Social Statisics of Cities” published in 1886.

So this blight actually preceded Katrina?

Yes, very much so. The first exodus occurred in the early 1960s as a phenomenon of white flight following desegregation. Later waves occurred again in the 70s and early 80s, as people cited reasons including declining public schools and increasing crime. In the 1980s and 90s, the black middle class departed historic New Orleans and settled in modern suburban subdivisions in the low-lying eastern half of the metropolis, which had been dissected by navigation canals and lay proximate to eroded coasts and surge-prone gulf waters.

How could people be encouraged to settle on higher ground, then?

Any official policy to direct people to higher ground risks re-invoking the bitter conflicts of the great footprint debate. If the City Council members took it upon themselves to incent people to higher ground, it would implicitly suggest that there was something risky and wrong with lower-lying areas—and that would meet with great resistance from neighborhood associations and realtors there. Politicians are naturally sensitive to their constituents. So don’t look to local government to do the encouraging.

As for me personally, as a geographer, I’m often approached by people considering buying a house or renting an apartment, and they ask me where they should look given the hydrology and topography of the city. I’m more than happy to unfurl my topographic maps and give them a little lessen in the historical geography of the city! But policymakers couldn’t do that without inciting a civic fight. It’s illogical, but not inexplicable.

There are both financial rewards and penalties for moving to higher ground. For one thing, the flood zone determines what kind of insurance coverage you can get, with higher ground of course being better. However, real estate is often cheaper in the low-lying areas – not necessarily because they’re more flood-prone, strangely, but because they’re less historic. Again, there aren’t as many historic neighborhoods in lower areas because those areas weren’t available for building until after 1900.

If policy isn’t the answer, what can the City do?

There is a move afoot already to increase population density through zoning in historic neighborhoods—that is, to return neighborhoods such as Bywater to their pre-World War II densities. Some of the open lots I identified are currently zoned only for commercial use. By changing the zoning to mixed or residential use, government could subtly shift population to higher areas without explicitly speaking negatively about low-lying areas.

What about the private sector?

I’ve personally inspected most of these lots just by biking and walking around the City. There is already a fair amount of infill development going on in these areas. And historical secondary commercial corridors such as Freret Street, St. Claude Avenue, and Oretha Castle Haley Boulevard are enjoying notable resurgences. They do not appeal to developers because they’re topographically high; they appeal because of their historicity. And because of the historical geography of the city, “historic” means “higher ground.” The use of overlay districts has helped these corridors as well, by encouraging certain desirable land uses.

Recent signs of life in New Orleans include these scenes from the Freret Street corridor. Left image shows an image from the Thirteenth Annual Mardi Gras Indian Hall of Fame, shared by Positive Vibrations, an organization that sponsors art as a vehicle for community and issues fellowship grants to teen musicians. Right image is from a PBS slideshow depicting community design activist Bryan Bell building a community bus shelter. See end of this article for links to original content.

Let’s say that you are a legislator or possibly a developer with resources to do something big. If you had the power to make real changes, what would you do?

That’s a good question… it takes me out of my comfort zone as a solitudinous archival and field geographer, and into the raucous din of public discourse [laughter]. What I would really like to see will never happen – I would like to see a city that never moved into these low-lying areas in the first place.

I would see a City with its pre-1900 footprint when 95% of the population lived on higher ground, on the natural levees paralleling the Mississippi River. I would bring back those intricate and textured neighborhoods and their panoply of architectural styles reflecting the contributions of the myriad cultures, regions, and ethnicities that made up the City. I’d like to have an intimate, walkable experience that wasn’t dictated by automotive transport.

I would like for urban expansion to have occurred laterally up and down the Mississippi River, where the high ground is, rather than latitudinally toward the low ground by Lake Ponchartrain. A more snake-like shape rather than the spread-eagle shape of the conurbation we currently have. I wish those low-lying wetlands had never been drained. We could have used them to store excess rainwater, and to buffer storm surges that instead threaten neighborhoods and people.

This would take massive amounts of money and citizen concurrence, and it’s not realistic to think that we can turn the clock back no matter how much money we have.

Suppose that an existing legislator or private developer were to approach you as an advisor. How would you inform their decisionmaking?

I’d look to what’s currently in the public discourse at the neighborhood level. Local officials could encourage zoning for increased density and infill development. I wouldn’t couch it as trying to get people to live above sea level. I would look at what’s currently already working. Officials could encourage or allow individuals to build apartments in the back of their homes and rent them out.

However, I must point out that there is stiff neighborhood resistance to some of this, and their main concern is that residents won’t be able to park in front of their homes anymore. But fears are somewhat exaggerated. We’re talking about tiny, incremental density increases, not dramatic ones. And these neighborhoods are already depopulated, even since 2005. My neighborhood had 5100 people in 2005 and only 3800 people today—and it’s historic and did not flood. So there’s plenty of room to grow back. I don’t think automobile storage should drive urban planning.

So most of the neighborhood opposition is rooted in the parking issue?

There’s also a suspicion that the people promoting higher densities have ulterior motives, other than societal good. There’s a feeling that they must be involved somehow in the real estate industry, or otherwise seeking to profit at others’ expense.

Although the major civil engineering that drained the New Orleans backswamps to allow for human habitation didn’t occur until 1900, another driver of geographical change was the need for shipping lanes. This 1861 map shows both elevated areas and major shipping channels. Image courtesy Richard Campanella.

Do people even want to live on top of each other the way they did in earlier times?

Building in an open lot is one way to increase density, but another way is to increase the number of people living in existing buildings. I’ll give you one example that is a rather humbling admission. My wife and I live in a 2000 square foot shotgun house that was built in 1893, and was originally a double that is now a single. At the time the house was built, the neighborhood was teeming with children. Two families of four living in our house meant eight people living above sea level. Now, with my wife and I living in that house as single dwelling, there are only 2 people in 2000 square feet of space.

It’s humbling to realize my own hypocrisy here. I should convert our house back into a double and rent out the space. But I’m not! This points to deeply rooted American social and cultural issues that are embedded within the density question, and also in the population shifts to low-lying areas. People today want more living space. We no longer live in the extended families of our great-grandparents. Children move out upon adulthood. We can’t pretend this cultural change never happened. This is somewhat counteracted by other trends, namely the rediscovery of inner cities by the same white middle class that fled them 30 or 40 years ago.

What is the architect’s role in promoting healthy change? Should architects be taking on a leadership role or should they stick with the traditional client-driven design model?

Now that I’m teaching geography at Tulane’s School of Architecture, this is a particularly pertinent question to me. The role that architects can play is to recognize that design and materials alone don’t make buildings sustainable. Location matters as well. A well-designed green building erected in an isolated rural area or in a far-flung flood-prone subdivision is not a green building, despite the great effort that went into design and materials. If it’s too remote, you lose the architectural sustainability advantage because the occupants will depend on auto transportation to get there. I think architects should consult topographical maps before they sit down at the drafting table.

Whether architects should take more of a leadership role… well, they may not have the opportunity to advise on site selection. Not if the client comes to them and already has the land selected. If the architect can get involved in the project early enough, they can play a significant role in site selection. If would give them an important opportunity to exercise geographical judgment.

What about public education campaigns to raise awareness of the availability of these open plots?

This already happens on a decentralized, ad-hoc level. Ever see those billboards saying “If you lived here, you’d be home by now”? That might encourage people to make an initial spatial decision to live closer to the inner core, which in New Orleans means living on higher ground. The more people want to make that decision, the more motivation developers will have in converting those open lots to habitable spaces.

In terms of my own effort to educate the public, I emphasize in all my lectures that New Orleans is not unconditionally “below sea level;” in fact, it’s almost precisely half above sea level—and this higher ground is a precious natural resource whose use we should prioritize for human occupancy. Recent research in sustainability suggests the value of cities and urban living. If you want to live sustainably, don’t live out in the woods off the grid. We’ve romanticized living in isolated cabins as being in environmentally benign and “in touch with nature,” but it’s an illusion.

Currier & Ives, “City of New Orleans” shows the city’s development by around 1880, including settlements and a lively river traffic. Image courtesy Library of Congress, as provided by Richard Campanella.

Didn’t people realize that the land was sinking, and that the various canals were causing environmental disasters?

I should distinguish between two types of canal: municipal outfall canals, which drain runoff from the city proper, and navigation canals, which were built for shipping throughout the Louisiana coastal region. The former occasioned the sinking of urban soils; the latter occasion coastal erosion and salt-water intrusion in the rural coastal periphery of the city.

Yes, people realized the soils were sinking; that realization came for Jefferson Parish in the 1970s, when a number of houses actually exploded because foundations cracked and gas lines exploded. New codes were put in place requiring pilings beneath slabs, but that only minimizing the cracking of the slab. It does not prevent the neighborhood from sinking. Once all the drainage apparatus was installed and people invested in the new subdivisions, soil subsidence became a problem that simply had to be suffered and dealt with through more and more drainage capacity. It was too late. Urban occupancy builds momentum; prior investment in cities carries with it inertia for continued investment despite increasing risk. There’s both bad and good in this: that inertia is on the reasons why cities often prove to be so resilient. But it sometimes lays the groundwork for the next disaster.

What’s the message that you would like to convey to our readers as the most important takeaway?

It is simply this: we have a valuable and scarce resource—topographic elevation—which ought to be used to the utmost degree for residential occupancy, especially given the lessons of Hurricane Katrina. By populating these above-sea-level parcels, we gain an additional benefit in mending the tears in the historic urban fabric that have opened up since the 1960s. If you look at the satellite images of Katrina flooding, you’ll essentially see the City’s circa-1900 footprint in the unflooded areas. Without closing down any areas or displacing anyone, we can make the best use of this great resource.

References for further reading

Professor Campanella has a very large body of work on his web site, both books and perhaps several hundred articles and research papers. Of these, the most relevant resource for understanding this article would be his book Bienville’s Dilemma, which is an exhaustive examination of the population shifts, agricultural development, and natural disasters occurring throughout the City’s history. Campanella spices up the narrative with vivid first-hand historical accounts, and his writing is fearlessly incisive and direct. You’ll learn more than you ever wanted to know about canals, levees, social hierarchies, and other fascinating topics!