David Winslow on the Guerrilla Urbanism of DIY Neighborhood Improvements

by Rebecca Firestone with Mark English AIA | Interviews

David Winslow of San Francisco’s City Planning Department talks about “living alleys” and walkable neighborhoods. “Home to me is a neighborhood where I can get basic needs met… Having a place to go outside of my own house… a corner cafe where they know me by name. It’s having public spaces that are functional and comfortable.” (Photo: green alley, Montreal, courtesy David Winslow)

The First Parklet

When it comes to parklets, the little pop-up sidewalk meeting places that reclaim parking spaces – or usurp them, depending on your viewpoint – “we can lay it all at ReBar’s feet,” according to David Winslow, Architect and Urban Designer at the San Francisco Planning Department.

ReBar had done the first parklet in 2006, partly as a statement against a car-centered planning culture that marginalized pedestrian and bicycle use of city streets in favor of private automobiles. ReBar’s guerrilla act was “a temporary occupation of parking space for a day, a celebration of use and design.”

Linden Alley

Winslow and I were talking about another San Francisco project, Linden Alley. Tucked away off of Gough, it had been a spot in need of a cleanup for a while. Then, one day in 2006, a little-known outfit called Blue Bottle Coffee opened a pop-up shop inside a parking garage. “This was artisanal, hand-brewed coffee, just for you,” said Winslow. “The wait became part of the experience, and a good excuse to meet and get to know the other customers. It became a little scene.”

It started with just the coffee shop. After a time, it became obvious that the existing sidewalks were too narrow to allow the addition of streetside tables, and that’s when ideas really took off. “Loring Sagan, the building owner and founder of Build, Inc. and I brainstormed about doing something, and the idea hit us: ‘What about a living alley’?” said Winslow. Within days of this inspiration, Winslow was approaching Marshall Foster, who was Mayor Gavin Newsom’s director of City Greening Initiatives (aka the “green czar”).

Neighborhood activism transformed San Francisco’s Linden Alley from a neglected street into a living alley. Blue Bottle’s pop-up in 2006 started the ball rolling on Linden Alley’s renewal. Dark Garden, right next door, has been selling custom-designed corsets and Edwardian finery since 1994. Photo: David Winslow

“In 2006, Gavin Newsom was looking to make his mark as the Mayor of San Francisco. He wanted to promote San Francisco as the greenest, most sustainable city in the world.” Marshall was highly supportive of the idea to transform Linden Alley, providing many helpful suggestions. “One thing he said was, Why don’t you apply for a Community Challenge grant?”

Design and permitting took another 2 years, as it went through multiple revisions from multiple City departments, including approval by SF board of Supervisors… the project had to consider accessibility requirements, emergency access vehicles, fire codes, and a myriad of technical details. In 2008 they got the permit, and afterwards secured the remainder of their funding.

The half-block project of Linden Alley in San Francisco took 4 years to get approved and funded, and only 2 1/2 months to actually construct. Reclaimed granite from demolished curbs became sculptural benches with plantings, for sitting and relaxing. Photo: David Winslow

Then, a final hurdle threatened to derail everything. “DPW required a pledge to maintain the street, and $2M in insurance for liability since we were changing the street from a standard design. We spent another year on the liability issue… people just didn’t want to sign the indemnity.” There was much fidgeting. People that had been involved and committed from the start began to back away.

“Eventually we realized that not everybody had to sign it. Just SOMEBODY had to.” An insurance policy cost $2600 a year. Eventually David Winslow and Loring Sagan (building owner for Blue Bottle, partner in Sagan Piechota design firm) took on the policy themselves. “I’m an architect, and architects have to be OK with risk. Having liability is standard in architectural projects already. It’s nothing new.”

“Finally, just before construction was ready to start, the Director of the Public Works Department suggested checking the condition of the pipes under the street. It turned out that there was an aging, 100-year-old sewer line that was due for replacement anyway. There was Federal stimulus money available at that time. So the street was torn up and then re-paved. DPW posted the work notice within 2 days. The work itself took 2 1/2 months.” Raising Linden Alley required new curbs and sewer outlets.

Market Street-Octavia Plan

When I asked whether Linden Alley came out of ReBar’s original parklet project, Winslow replied: “Linden Alley was part of the San Francisco zeitgeist in the mid 2000’s. Larger planning efforts included the Market Street-Octavia Plan, which was highly influenced by the Hayes Valley Neighborhood Association, as well as City Planning.”

The Octavia Street corridor in San Francisco has been transformed from a transit corridor into an open recreational space where pedestrians, bikes, and cars all share the space as equals. Photos: Rebecca Firestone

“Linden Alley wasn’t your typical Planning project, either,” says Winslow. “Typically you wait for a client, build a building, and then publish it in a magazine.” This was design, permit, fundraise, and build – all in a public right of way for public use.

Turning Freeways Into Boulevards

The roots of the Market-Octavia Plan started with the Loma Prieta earthquake of 1989, which rendered the central freeway “unfit” for continue use. “It was a double-deck freeway,” explained Winslow. “To make it usable, they would have had to rebuild it as one level, meaning much wider. This would have been WAY too close to the existing buildings, literally inches away from them.”

The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake damaged San Francisco’s central freeway, leading to a 10-year debate over its replacement.

Eventually, after 3 ballot initiatives and only 10 years of haggling, the City of San Francisco decided to tear down the freeway and replace it with a boulevard (formerly Octavia Street) – a more European solution. Two of the key people spearheading the ballot initiatives were architect Robin F. Levitt, a member of the San Francisco Bicycle Coalition, and neighborhood activist Patricia Walkup, founder of the Hayes Valley Neighborhood Association.

The Octavia Boulevard schematics were designed by Allan Jacobs, the former Director of San Francisco Planning and emeritus professor at the Department of City and Regional Planning at the University of California at Berkeley. San Francisco DPW provided the construction drawings and the construction services.

“Americans love freeways,” said Winslow, “but Europeans prefer multi-way boulevards, like the Champs Elysees. They carry the same volume of traffic. Yes, they’re a little slower, but they’re living streets, where people can mingle and get to know one another.”

Books like “Great Streets” by Allan Jacobs and “The Boulevard Book” by Allan Jacobs, Elizabeth MacDonald and Yodan Rofe influenced San Francisco’s plans for the Octavia-Market Street area.

Moving Away from Car Culture

Urbanists like Allan Jacobs refuted earlier Modernist visions of urbanism, such as le Corbusier’s “radiant cities”. These shining utopias consisted of massive freeways and large apartment blocks, celebrating efficiency and technology over livability and human-scale environments by moving uses and people off the streets. The result was that streets were empty and devoid of life. Sometimes, what came to fill up the vacuum was less than ideal. (Radiant Cities has been widely cited as leading to notorious 1960s-era public housing projects.)

San Francisco’s Commercial Street alley offers an ideal lunch hour hangout in the Financial District. Photo: David Winslow

The Market-Octavia Plan included some things that were radical notions in San Francisco at the time: eliminating parking requirements for new construction, and “recognizing good design that was not Victorian”. It consciously promoted higher density development and multiple transit options. Barrier-imposing freeways were to be replaced by city streets, new buildings and open space.

Most radical of all, a departure from the top-down approach to urban planning: instead, the plan was specifically geared to enable residents to develop their own designs and improvements for living alleys to compensate for the busy arterial streets and lack of recreational space. Planning and the neighborhood envisioned a network of living alleys: green spaces and walkable destinations in between major arteries.

Planning wanted instead to focus on augmenting major streets with a network of living alleys: green spaces and walkable destinations in between major surface arteries.

Whom Do We Want to Attract?

Of course, some people had concerns that all these new public spaces would fill up with the “wrong” people. “It’ll just be trashed… a waste of money.” That’s a sensitive topic right there – who, exactly, is an “undesirable”? That isn’t what happened with Octavia, though. Winslow thinks it’s because there are enough other users that everyone just blends in.

Which would you rather have, an empty alley full of trash and graffiti, or a lively outdoor market that’s safe, friendly, and teeming with local enterprise? Vancouver “livable laneway” photo: David Winslow

And, Linden Alley before its facelift was apparently not very swanky, either. The stereotypical signs of neglect – graffiti, trash, used condoms, needles – aren’t there now, or not very much. Why didn’t it get trashed? “We didn’t worry about that, actually,” says Winslow. “We were too busy navigating the booby traps of financing and permitting.”

“Today… it’s held up pretty well,” he told me. “Users and neighbors have volunteered to pitch in and clean up… the Blue Bottle staff does a trash pickup at the end of every shift. There’s a gardener, and other volunteer trash pickup.” We talked about how Linden Alley is a day use spot, rather than a late-night bar scene.

Defensive Architecture Becomes a Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

Winslow had referenced “The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces” by William H. Whyte, which I happened to have on my bookshelf at home. It’s a set of guidelines for creating successful urban parks and plazas, backed up by reams of observational data collected by Whyte and his associates. Whyte devotes an entire chapter to the mistaken notion that plazas should be designed to keep bad people away. All that does is keep EVERYONE away, which perversely attracts exactly the elements you didn’t want because there’s no one else there.

Whyte writes, “Who are the undesirables? For most businessmen, curiously, it is not muggers, dope dealers, or truly dangerous people. It is the winos, the derelicts… the most harmless of the city’s marginal people… bag women, people who act strangely in public, “hippies”, teenagers, older people, street musicians, vendors…”

According to William H. Whyte, businesspeople’s idea of “undesirables” includes street musicians and “people who act strangely in public”. Isn’t that what gives San Francisco its charm?

Whyte says that inhospitable approaches lead to a vicious cycle. “Places designed with distrust get what they were looking for.” According to Whyte, hospitable places have ample seating, attractive access points, and a tolerate approach to behavioral norms. “Seagram’s management is pleased people like its plaza and is quite relaxed about what they do. It lets them stick their feet in the pool… The sun rises the next morning.”

I was trying to reconcile this philosophy of hospitality with the “Defensible Space” notion promoted by Oscar Newman. David Winslow pointed out one key similarity: eyes on the street. In the Living Alleys Toolkit, designs that allow people to see what’s going on in the street are encouraged. (See also Elijah Anderson’s book “The Cosmopolitan Canopy” for some interesting and convincing descriptions of the hospitality principle at work.)

One common thread between the approaches of William H. Whyte’s “The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces” and Oscar Newman’s “Defensible Space” is the concept that “eyes on the street” make it safer.

Winslow’s Current Role

So what’s on your plate now? I wondered. One thing is he’s doing is sharing the lessons learned from Linden Alley. The Market Octavia Living Alleys Toolkit helps to guide neighborhood associations with their own neighborhood improvements. “There’s still some funding from the Octavia efforts,” Winslow noted. “There’s maybe $1.5-2M still earmarked for living alleys.” SF Better Streets also has an online design guide explaining when and how to use design elements like curb extensions (bulb-outs) for traffic calming, to create more pedestrian-friendly environments.

The Market Octavia Living Alleys Toolkit outlines all the requirements for getting a project permitted and approved, and also provides extensive design examples, background, case studies, and other suggestions.

And then I said, “You won’t want to answer this question, but … what would you do if you were head of Planning or you could wave a magic wand and be King for a year?”

Winslow replied, “Here’s my dream vision: If you were walking around Hayes Valley, you could find a network of green, pedestrianized alleys. Former garages are converted into housing and small retail stores, with people walking, biking, and socializing.”

What Does “Home” Mean To You?

“Here’s what ‘home’ means to me. It’s a neighborhood where I can get basic needs met. It’s knowing people. Having a place to go outside of my own home. Having a living room outside of my home at the corner cafe, someplace like Cheers where they know your name. It’s having public space that is functional and comfortable.”

Improving the Planning Process

Back to the king-for-a-day fantasy. “California Governor Jerry Brown has some pending legislation to streamline the Discretionary Review process and CEQA, state-wide. However, I would like for us to see this as an opportunity to revise our code, starting from scratch, and to make it simple – clear – direct. More form-based. This could achieve many things that we are trying to do now through Discretionary Review.

“The City of San Francisco should wholly embrace it as a chance to clarify our aspirations. It’s evolved over time gradually cobbled together, but now it’s time for a fresh start.”

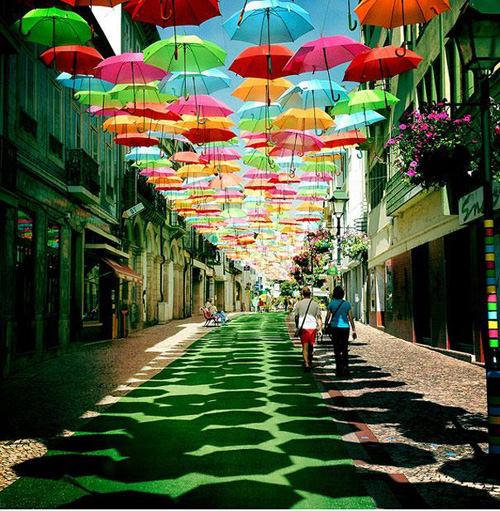

This floating-umbrella passage is in Portugal, but I’m sure we’ve done these installations in San Francisco as well. Photo: David Winslow

Reading Recommendations

I asked Winslow for recommendations for further discussion. Who were the most influential urbanists? William H. Whyte, author of The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces, and who also narrated a video by the same name; Christopher Alexander, although Winslow doesn’t agree with everything in A Pattern Language; Jan Gehl, Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space; Jane Jacobs “of course”, The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Oscar Newman, Defensible Space; the aforementioned Allan Jacobs, author of Great Streets.

David Winslow will be a panelist on a forum September 22, 2016 from 6-8pm as part of the Architecture in the City festival. Titled “From City Project to Vibrant Neighborhood”, this Lecture panel will explore the urban living spaces that we call home.

Tickets available at archandcity | Lectures

Craig Hamburg | The Architects' Take

20. Oct, 2016

[…] architect David Baker, housing advocate Sonja Trauss, architect Anne Fougeron, FAIA, City Planner David Winslow, as well as Craig Hamburg, who has collaborated with a number of the panelists on various […]