Craig Steely Part 2 – Inside Track

by Rebecca Firestone with Mark English AIA | Interviews

“To me, a good client is someone who’s really interested in the process. Someone who really WANTS to be involved. I demand it, actually… I only work with people that I like and respect. The point of taking only good work is that you’re more invested in it. I love what I do and don’t want to get burned out.”

– Craig Steely, Architect

Craig Steely is not one for pomp and circumstance. The second part of our interview included Mark English as well as Rebecca. Craig arrived on a skateboard. Of course, we all met at Tartine, a San Francisco pastry shop so exclusive that you have to make an appointment there to buy a loaf of bread! Fortunately, no appointment was required to get a mocha, although I did have to cadge a dollar off him because I’d forgotten that I had run out of money…

In this part, Mark English’s questions appear in italics.

The house known as “Lava Flow 7” by Craig Steely features cast-in-place concrete and a tensioned fabric roof.

Mark English: Thank god there’s some modern work in San Francisco these days. When I first got here there was nuthin’.

Yeah, at one time if anyone used corrugated siding I thought, “Hooray!” At one time, anything modern in San Francisco was a rarity. Now the City has enough modern architecture that we can afford to be critical. That’s a good thing.

Some areas of San Francisco really do have a history, like North Beach, with the old Italian neighborhoods. Less false preservationism…

I used to live in North Beach when I first got back from Italy [after school]. I loved hearing all the old ladies speaking Italian. The place was on Kearny and Green, a cottage behind a house. We lived there until my motorcycle and furniture-building hobbies outgrew our kitchen space.

It’s interesting working out of your own house, isn’t it?

It either breaks or seals the deal for potential clients who come to visit. They can see for themselves what they’re getting into. It gives me freedom. This dialogue at the beginning makes for great clients. I’m totally honest with them about pricing, construction, and how we’re going to work on their project.

What does this driftwood hut have in common with the new house shown below, besides that both are recent designs from architect Craig Steely? Both are examples of a strong, single idea informing the design. Images courtesy Craig Steely Architecture

And then the clients interact with one another.

When my clients serve as references, they also act to pre-screen new clients for me. They can call my attention to something if they see a red flag. One potential client who had impressed me favorably went and talked with a few other people, and one of those former clients sent me an email saying, “WHOA! This guy needs to be straight with you! He’s too fixed in his ideas about what he wants.” It could just be that the potential client wasn’t as frank with me, but was more open with the other client about what he really wanted.

In another situation, a client’s negative reference actually worked in my favor. The potential client called up the reference [husband and wife] and spoke to the wife, who said that I spent too much time detailing. The potential client thought this was great! He wanted someone with an obsessive attention to detail. The point is to let the new clients know what they’re getting into.

I see you did an apartment in the Fontana building, where we just completed a project. Moving even one wall was a huge issue because of all the pipes. How did you fare in working with the management and the board?

With a building like that, every wall is full of pipes because the mechanical is all on the roof. My project was a 4-bedroom 5-bath penthouse, and we essentially made it into a one-bedroom by removing walls. We increased the electrical service from 100 to 150 Amp and had to shut the power off for the entire building for a day! That was a tough sell. This was for a steam shower. We could have done it with gas; we found a gas pipe on the roof that would have let us do it that way, but a Fontana Board member said, “No gas! It’ll explode” so we did it electrically instead.

In this San Francisco penthouse remodel, “Ludwig Apartment”, Craig Steely opened the space to sun and views, combined rooms for better flow, and re-assigned functional spaces for elegance and simplicity. Built-in woodwork is custom stained walnut. Photo: Rien van Rijthoven

This particular Board member had served in the Navy in the Pacific once upon a time and he had a very military thought process, which we jokingly referred to as “vague and to the point”. I did my best to relate to him in a very “yes sir, we’ve got our best people on it, sir” attitude. If you can find a way to relate to someone, then you are more able to come to an understanding.

In our project there, we did a radiant floor and had to sell that to the building management.

Didn’t that raise the floor and make the ceilings too low?

No, not really. We pushed up the ceiling in a few places and used small Pex pipes. The main thing they were worried about was the water. I showed them a small bucket that contained all the water for the radiant system, and it was a lot less than a conventional radiator system, with its virtually inexhaustible supply of water.

In the penthouse, I used small radiators that were hidden inside a notch in the walls. Apartments are a tough job – you have to work around the building infrastructure, condo boards, and other tenants.

A second view of Craig Steely’s “Ludwig Apartment” showing the San Francisco Bay. Photo: Rien van Rijthoven

You and I share an educational background at California Polytechnic. Cal Poly attracts people who build, people who work with their hands. Before the latest code changes came out, I used to do all my own structural – and I really liked it.

I love doing that part of it, too! We’ll take a stab first, and then give it to the structural engineer. Thinking about the structure is, for us, a part of the design process. By the time we hand it off, the engineer knows what we’re trying to do and can make better recommendations. Builders, too. Instead of spending time on detailing, we can tell them, “We don’t want to see too much flashing,” and then they’ll say “Well, why don’t you do it this way instead?” and it’ll be a better idea.

Which structural engineers do you use?

In San Francisco, Val Rabichev. In Hawai’i, Ray Keuning (who’s retired now) and Wally Vorfeld. They’re very hands-on and they’re willing to accommodate. I like smaller firms. A big engineering firm tends to hand the project off to a more junior person with less experience. I like working with the older guys, the ones who have those 10,000 hours of experience that Malcolm Gladwell says you need to be an expert in anything. They have a better command of the craft.

How did you get your first Hawai’i project?

Through Robert Trickey. He’s a very well-respected San Francisco furniture and upholstery designer. A few years before, I had brought him a modern Danish couch to restore. He truly understood the mechanics of unbuilding and rebuilding it, and a great working relationship came out of it. We bonded over that project, and when he bought his property in Hawai’i, he called me.

The engineering behind Craig Steely’s “Napa River House” is intended to float the living room on a special pillared base in order to preserve the root structures of the surrounding oak trees. Image courtesy Craig Steely Architecture

Every custom project is a prototype. This makes it hard to get comparable bids, because there’s no chance to do it a second time.

There are different personality types, too. The owner’s personality and needs are what drives the project. Some people are qualitative-based, others are quantitative-based. Their attitude also depends on their occupation, their station in life, even their basic happiness. With prototypes, you’re going to make mistakes. You have to take the attitude that the mistakes will end up making the project better in the end.

Two interesting details that stood out about this photo of Craig Steely’s “Lava Flow 2” house were the lowered cabinet on the left, which makes for a more visually interesting composition, and the circular skylight above the round bath/shower stall that is visible from the adjoining space as well as the bath itself. Photo: J.D. Peterson

What are your tools for design?

Drawing and model-building. I like 1/4″ scale physical models. For computer visualization, I’ll draw plans and sections, and then my staff puts it into Rhino 3D for fast visualization. The clients can see right away what the status of the project is. There’s none of this “I’ll get back to you in 2 weeks with a rendering”. Renderings can be misleading if you don’t know what’s important. Sometimes people will look at a rendering and focus on some temporary texture like the wood grain, instead of looking at the form. Clients still need to use their imagination, to understand that the rendering isn’t exactly what they’re getting – it’s an abstraction.

With a physical model, you’re more invested. But, happy accidents can occur which aren’t part of the plan.

It’s obvious to me when people design solely in model. The model ends up looking great, but the change in scale to “full-size” doesn’t work. Changing formats can be helpful, though. I like to draw and I can lie to myself with a drawing, but that lie becomes apparent when switching to another medium. When that flow of design slows down, it’s time to change medium or format. Seeing things in different formats helps the design. It helps me get to what’s really important.

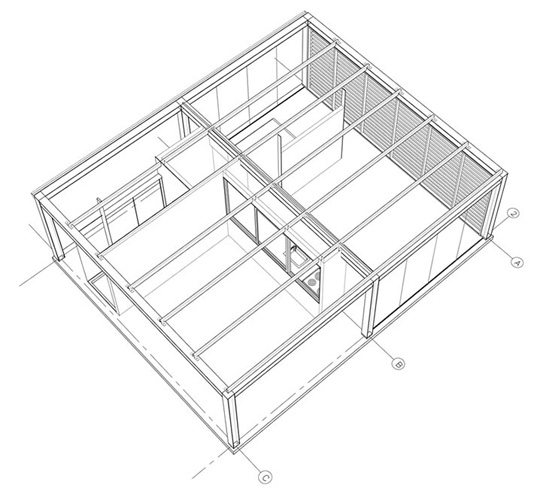

Craig Steely’s design for “Lava Flow 6” is a simple and efficient steel frame house for a remote Hawai’i location. “Thinking about the structure is, for us, a part of the design process,” says Steely.

You mentioned the importance of sticking to one design idea.

It’s a beginner’s mistake to put too many ideas into one house. They might feel that it’s their only chance, their one good client, and it’s now or never. As designers get more experience and more confidence, they feel less compelled to use all their ideas in the same project.

Sometimes models and materials can be misleading to clients who don’t know what they’re supposed to be seeing.

I had one client for a house in Hawaii who said, “Do what you want.” So I built a model, boxed it, and sent it to him with no explanation. The client responded “Aggh! Why don’t you just do what you did on this other house that you did 3 years ago?” I had to explain things to him in a way that he could accept, and I said, “I’m in a better place than I was 3 years ago. Trust me – it’ll be better.” And to his credit, the client stepped up to the plate. He realized that if the architect is happy, the client will be happier, too. Happy architects make better houses.

The themes that appear over and over again in Craig Steely’s work are well developed by the time of “Lava Flow 5” – steel framing, simple lines, and most these houses seem to have the presence of water or a pool feature as well.

What about Bauhaus? I saw a Bauhaus exhibit in Berlin. The craft integration was intriguing, but it went way beyond that. The written diagrams scared me – the social hierarchy diagrams, for example.

What’s good about the Bauhaus was the emphasis on craft and functionalism as a simple idea that informs the design.

That gets us back to the importance of the single idea…

Dieter Rams is one designer who has embraced this. He was head of industrial design at Braun for 30 years. The architect, Mark Mills also talked about the simplicity of a strong idea. I can see the single idea even in things like burlwood furniture – things typically associated with hippie art, or California art. If one looks hard enough, one can see beyond the “hippie” trappings to the core of an idea. Even God’s-eye place mats and macrame could be compared to something like a Dieter Rams turntable – creation guided by an underlying set of rules that are self-created. Even macrame follows this: you have a basic rule for execution, and then there’s technique, balance, form.

Not all of Craig Steely’s work is in Hawai’i. “Xiao-Yen’s House” is a vertical San Francisco hillside house with the same steel frame and roof pavilion re-interpreted for a different locale. Photo: Bruce Damonte

I think of it as intention. Buildings are the artifacts of intention. Archaeology interests me for that reason, too.

The intention is like a map that shows how inherent human conditions can cross time and boundaries. Archaeology is dirty and very labor-intensive. It’s very honest.

The intention could be different, though. A building can be designed with the intention of winning awards. Or one could have a whole bundle of intentions.

If a building has a clear intent, that intent should be obvious – at least to other architects. Though even an untrained person can sense when an intent is present, even if they don’t know exactly what it is.

Cool article « Jim's Hiking Trail

10. Oct, 2011

[…] Craig Steely Part 2 – Inside Track […]

Greg Oaksen

21. Aug, 2014

Great work! And great interview!

Roberto.gonzales

17. Mar, 2015

I likely all Craig’s design. My favorite is ” Napa River House “.