Sculpting the Land: Arterra’s Landscape Architecture

by Rebecca Firestone with Mark English AIA | Interviews

“If we are successful in our design, the site is essentially preserved or restored to a naturally sustainable state. The building will be aligned for solar aspects, and will be so well-sited that it appears to emerge from the land.

We provide a sense of magic and well as a workable landscape in which water is conveyed, plants grow naturally, the soil is healthy, and wildlife can thrive. Through good design we link home to site and provide a sensory feast for our clients with all the sights, sounds, fragrances, and perceptions of being in a deeply meaningful landscape. The landscape is living, breathing, and ever-changing. From this, a unique sense of place emerges and begins to tell its own story.”

– Vera Gates and Kate Stickley, Arterra LLP

Kate Stickley and Vera Gates of Arterra LLP in San Francisco have both been in the landscape architecture business for over 27 years, and in a thriving partnership together for the past 8 years. These days, with so many design firms either cutting back or closing their business, it’s a refreshing change to see a successful woman-owned design firm where the principals really love what they do. Their offices are serene and airy; projects and sketches cover the walls, and a rear deck provides a refreshing view of San Francisco’s Potrero Hill neighborhood.

Interviewer’s questions appear in italics.

Arterra LLP is a San Francisco-based, woman-owned landscape architecture firm. Left: Vera Gates. Right: Katherine B. Stickley

Family Background

Vera: I grew up on a Vermont dairy farm as a 7th generation farmer. We had 300 acres of tillable land plus another 300 acres of woodland and swamp. We raised dairy cows and worked the land. We also tended the woodlots for timber and maple sugar. We built what we needed and used what we had: timber and stone from the site itself. My dad loved doing stonework, while my mother was the dairy calf expert. My parents still grow a huge “victory garden” every summer. My dad has a new project – converting methane gas from cow manure into energy and selling it back to the grid. That is his idea of retirement!

I had 3 younger sisters and a big crew of cousins – literally a truckload of kids! We grew up doing chores together, cleaning fields together, building together. When I was 10 we built our house, and it was the single most influential aspect of my childhood. To see this dream emerge for my parents and to have the help of our whole extended family was an incredible experience.

This "Hillside Transformation" landscape design by Arterra LLP is one example of the artful use of stone to create a rustic-feeling terraced wall. Photo courtesy Arterra LLP

Vera: I took art when I could find it, in high school and summer courses. It was more crafts, though – building and making things. Art inspired me to weave together the agrarian side of things with the idea of sculpting the land more artfully. When I was a student at Cal Poly, a friend and I went to Manhattan for a week and visited every single art museum. The contemporary artworks and the architecture of the Guggenheim just blew me away. I saw landscapes in everything, and suddenly I saw the potential for art to emerge as a landscape of forms and composition. I began to explore landscape design as a sculptural endeavor. But first I had to learn about site grading – the actual process of moving earth to create or shape volumes, hills, flat surfaces.

This landscape by Arterra LLP titled "62 Degrees" got its name from the angle at which the garden is sited in relation to the lot. Photo: Michele Lee Willson Photography

Kate: My family background was a bit different from Vera’s. I had a suburban upbringing. We were the first phase in our subdivision, so there were a lot of open spaces and construction sites to explore. We were construction junkies! I crawled around the buildings that were going up, and built forts in backyards with materials from the construction sites. I used to leave my house in the morning with a pair of clippers and cut my own paths through the woods. There was a creek, which we would dam up. We’d go out to view it during storms, play on the ice when it was cold. We gained a real-time appreciation of the weather and micro-climates.

Kate Stickley of Arterra LLP spent her childhood damming creeks and building backyard forts using reclaimed materials from nearby suburban homes under construction. This project, "A Garden in the Redwoods", features a natural-looking creek that formerly flowed through a concrete channel. Photo courtesy Arterra LLP

Kate: My mom was a very creative person. She was one of the founders of the Delaware Center for Contemporary Arts, and she was always making art herself. She is a fiber artist now. When I was a kid, it was ceramics. I had contact with other creative people, mainly organizers in support of the arts. I liked art, but didn’t think about careers until a high school guidance counselor suggested landscape architecture. I loved being outside, loved to ride horses, so that together with the art made landscape design a good choice.

Early Mentors and Influences

Vera: I had an aunt in Berkeley. I lived with her when I first came to California at the age of 18. She was a guiding force, someone wise and brave enough to speak the truth. She was a professional woman, also – a Certified Public Accountant. She kept me on track and she was always right in her career advice. When I was debating whether or not to go for my license, she said to me: “You can’t ride the bus if you don’t get a ticket.”

The landscaping and exterior design of the "Family Country Home" by Arterra LLP complements the home, which was designed by San Francisco architect David Gast. Photo courtesy Arterra LLP

Vera: One professor that I had was Gary Dwyer. He was a sculptor, a photographer, and a landscape architect. He saw the world through a very different prism. He pushed me to my outer limits of discomfort… and he’s still doing it today. For example, in teaching us about design, he wouldn’t start at the beginning in a linear, methodical progression. He’d start at the end. He’d tell us to create an entry or passageway without telling us what that entry was for, or what the destination of the passage would be. There was no starting point. Then he’d ask questions that I couldn’t answer, and I’d have to start the design all over again. To him, using a recognizable form was cheating.

Kate: I recently attended an art opening by sculptor Brian Wall. He said that his favorite pieces were the ones he hated at the beginning. He’d ask himself: “But WHY do I hate it? What could be done to make it something that I like?” Many of his most successful pieces were started this way. People like Brian Wall are inspirations for me. I love learning how artists and designers personalize the creative process.

A second view of Arterra LLP's exterior hardscape and landscaping of the "Family Country Home" project, done together with architect David Gast. Photo courtesy Arterra LLP

Kate: My mentors were people who were able to see in me what I had yet to learn about myself. People who said to me, “You CAN do this.”

Do mentors have to be the same age, gender, or background as you?

Kate: I don’t think it’s necessary for every mentor to share one’s own characteristics, but it helps if you can get it. I had only one female professor out of all the landscape architecture faculty. She talked about things like balancing family and profession, and that was helpful.

Vera: It’s VERY important if it’s an option. Today, 50% of landscape architects are women. In our partnership practice, Kate and I mentor each other. We have a lot of women friends who are sole proprietors of their own firms, and when we get together socially for ski weekends or whatever, they always want to talk about business and bounce ideas off of us.

Who says teak lawn chairs always have to be painted white? A small color accent among the wildflowers helps the seating to harmonize with the natural surroundings. Photo: Michele Lee Willson Photography

Sharing Ideas and Mentoring Others

One place to share ideas is at professional gatherings. The American Society of Landscape Architects has annual meetings in a different city each year, with different themes. By contrast, some of the “green building” or “sustainability” training seminars aren’t as focused on landscape design; they’re more concerned with the building systems and technologies than they are with the site components. This isn’t to dismiss them – but maybe someday they won’t put the landscape architecture in the last 5 minutes of every presentation.

Professional gatherings also give you a chance to start giving back. You reach a point in your career when you begin to guide and mentor other people. When I had less experience, I was the one looking for guidance. Now I go to these conferences and meet people at dinner, and I make their day. When I first realized that, it was a great dawning!

There are so many people along the way who can give you ideas, feedback, and support. We are always willing to share with our colleagues. Mentoring for us is an ongoing exchange of ideas and information. Our efforts to build collaborative relationships go beyond working on projects together. We want to build strong business associations that will help our designs evolve and our businesses to grow. Within Arterra LLP, we are always exploring how to be better mentors to our young landscape architects, so that they have the support they need to flourish and thrive.

The "Jewel Box Garden" from Arterra LLP shows how careful attention to detail can make the most of even the smallest of garden spaces. Photo courtesy Arterra LLP

Collaborative Teams Can Create Better Designs

Within a project team, the level of collaboration varies depending on the project. Sometimes it’s the architect who sets the cadence, who has primary access to the client, and we follow suit. The buildings are already sited and our role is more limited. A more ideal situation is an “integrated design” approach, where the entire team walks the site together on Day 1, and shares in the client’s vision. We bring things to the table that other people aren’t schooled in. We are another set of eyes – we can spot opportunities for the building to interact with the site that others might miss.

It’s really the ideal of an old-fashioned charrette session, where everyone on the team shares their point of view – the biggest problems they face on the project, and the potentials that they see. Upon hearing one person’s challenge, other team members may be able to suggest alternatives that otherwise never would have occurred to anyone. This approach to problem-solving builds a collective group memory which can speed things down the road, especially if the entire team is involved from the very beginning.

Sometimes the site reveals the whole in a way that is only partially visible from the ground. This conceptual plan from Arterra LLP shows how the arcs and lines, transitions, passages, and focal points of the residence are contained within a circle inscribed on the land itself.

Creating a Sense of Meaning

A robust team effort results in a more meaningful project for everyone involved. We each identify the priorities for our phase of work, and look for common purpose and shared resources of construction. When everyone has buy-in on the design ideals of the project, we are all better able to deliver a built project that fits the site, the program, and the budget.With a more integrated design approach, you end up with a building and a site that really BELONG together.

A site has an engineering component, both for the house structure itself and for roads, drainage, grading of the land and such. The traditional approach is linear, as done by engineers. Engineers are problem solvers, and their job is to make it work. But we don’t just make it work – we make it work BEAUTIFULLY. For example, a straightforward engineering solution would be to put all the storm water piping underground. They wouldn’t necessarily consider making them intentionally visible.

So, which architects have you worked with in a collaborative way?

There are so many! Currently, we’re working on projects with Jonathan Feldman, Cathy Schwabe, Eric Carlson of Carlson Design Group in Colorado, and Jim Caldwell.

In a collaborative approach, each design professional gets a chance to share ideas directly with entire team, including the client. Above: in one design meeting, landscape designer Kate Stickley overlaid her different concepts of outdoor spaces over the architect's printout of the interior floor plans. Image courtesy of Feldman Architecture.

Favorite Landscapes

Kate: My favorite landscapes are actually ruins. I love Hadrian’s Wall, Hadrian’s Villa, the Forum. I like to look at a half-fallen arch and try to picture what it was.

Vera: Delphi, and the Mayan ruins in Yucatan. The siting of these cities was both scientific and spiritual, based on the movement of the sun and the seasons.

You'd think that landscape designers would like other landscaper's work the best, but Kate and Vera of Arterra LLP both love ancient ruins as well. Left: Hadrian's Wall in Britain dates from Roman times. Right: Mayan ruin at Chichen Itza.

Good Design and Sense of Place

What constitutes “good design”?

Kate: Good design speaks to you in a way that feels good. We’re surrounded by design all the time: handhelds, cars, furniture. For landscapes and living spaces, we like a sense of place and a grounded nature. Each project is unique and should be celebrated as such. And, we have found that one of the best ways to realize this goal is to work collaboratively. When the entire design and building team truly shares a vision, the final built project is infused with a distinct and memorable sense of place.

This "Contemporary Update" landscape by Arterra LLP conveys a compelling sense of place, an oasis that is both inviting and restorative. There's a lot to look at, and yet it's not too busy, either. Photo: Michele Lee Willson Photography

Our goal is always to design in the spirit of the place. We identify the essential, natural qualities of an existing site and we strive to conserve and protect these aspects. We look for the potential to transform the site into something more, something magical. We strive to achieve a sense of meaning and beauty in everything we touch.

Where once we designed for purely visual reasons, to create a beautiful landform, today this ideal has been tempered by function. It is less about the high art of sculpture and more about creating beautiful, meaningful landforms that work. We work openly to incorporate the functional grading, conveyance and storage of water, and unique planting systems into a visible and beautiful part of the design.

Site plan of Arterra LLP's design for "62 Degrees", a garden for a San Francisco home. The angle was chosen to align with an existing stair extending out behind the house, but Arterra co-owner Vera Gates joked that it could also refer to the average summer temperature in San Francisco.

Gesture

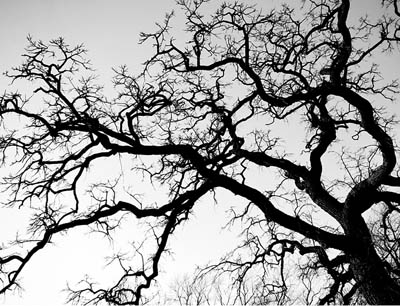

Vera: Good design is about the gesture of the landform. “Gesture” in this context means “parti” or “gestalt” or “overall shape” rather than a specific bodily movement or position – more like a unique signature. The human form has a gesture. Trees have a gesture. Architecture has a gesture. Each project has its own gesture.

In order for the built landscape to feel natural, there must be an ease of gesture. Any element that is over-thought, or over-wrought, will feel awkward and out of place. That’s another reason why collaboration is so important. The working systems such as stormwater drainage must be integrated into the overall design in a beautiful way, or they will stand out in a way that detracts from the design.

The sign of a successful project is that after it’s done, you can’t imagine the site WITHOUT the exact composition that was put in place. In fact, you can’t even remember what it was like before. If we are successful in our design, the site is essentially preserved or restored to a naturally sustainable state. The building will be aligned for solar aspects, and will be so well-sited that it appears to emerge from the land. If the gesture is interrupted somehow, it’s not as successful – it doesn’t have the same feeling of completion.

This winter tree silhouette shows a gestural quality that is consistent throughout. Even within the same species, individual trees can each have their own personality.

Finding the Sweet Spot

We begin our design with a site inventory and analysis. We try to identify the “sweet spot” – that one place on a site that feels magical and special. And, if we find it, we work to preserve and protect that spot, celebrate it. Far too often, though, it simply isn’t there. People feel this, that there is no heart to the garden, although they can’t always articulate why. But this “heart” is often what they are looking for.

Our design approach is holistic. We provide a sense of magic and well as a workable landscape in which water is conveyed, plants grow naturally, the soil is healthy, and wildlife can thrive. Through good design we link home to site and provide a sensory feast for our clients with all the sights, sounds, fragrances, and perceptions of being in a deeply meaningful landscape. The landscape is living, breathing, and ever-changing. From this, a unique sense of place emerges and begins to tell its own story.

Abstraction

Our blog profiles a lot of Modernist and contemporary architects, some of whom create very abstract, minimalist designs. In fact, one of our unstated missions is to convey an appreciation for some of these conceptual designs to a general audience. With landscape design, it’s harder to find really far-out, abstract work, possibly due to the nature of the medium, especially living plants. Plants are inherently representational, and they continue to grow and change over time instead of staying exactly where they’re put. This led me to the question:

Is it even possible to create abstract or minimalist designs out of such unruly materials as living plants?

Vera: Our designs aren’t really abstract, they’re more organic. One of the main goals is to minimize pruning and shaping. Something abstract and artificial like a cubical tree would require constant maintenance to keep that look. That’s not practical.

Kate: I like Dan Kiley’s works. He had a simple Modernist way, very ordered.

Vera: Our work is responsive to site. It takes on its own voice and evolves. There’s no abstraction simply for the sake of abstraction.

Andy Goldsworthy's art is often very ephemeral, but he also does permanent works like this stone cairn. All his works are pretty nifty and blend easily into their natural settings.

Vera: Our work differs from architects in that we are setting in motion a living, breathing place. It will evolve over time, over 5 years, and over 50 years. We want it to hold together continuously through changes that time will bring.

Trees are a sculptural aspect, too. Sculpture is not just about landforms or built forms. Sometimes we’ll work on a site that has existing trees. If it’s got a stand of oaks that are all around 50 years old, then they’ll all die around the same time. In that case, we might plant new trees of the same type nearby that would come to maturity around the time that the old trees die out.

Arterra LLP's project "La Jolla de Santa Lucia" worked around the existing stands of native California oaks.

Sustainability

What’s your approach to sustainability, now that “green” is such a hot topic?

Sustainability is more than a celebration of nature. What’s crucial to sustainable design is this: an integrated design team, correct siting, minimum site disturbance, and reducing resource consumption both during and after construction. We also incorporate food production into our designs as much as possible. We believe that it’s very important for people to know where their food comes from, and for children to be able to go outside and pick food.

The perception of what is “beautiful” is changing. The idea of planted roofs, seasonal creeks, and winter ponds is much more appealing to our clients now. They “get it”. The look of native and low-water-use plantings has become popular, and we’re finally moving away from seeing so much water-intensive lawn.

Some of the green guidelines specify things like “native plants”, but what does that mean exactly?

It means exactly what it says: plants which are native to the region. “Drought tolerant” is typically more of what we see, and includes a mix of native and non-native plants. Our landscapes aim for low water use, with no pesticides required.

The "Casa Esperanza" landscape design by Arterra LLP in California's Carmel region made extensive use of low-water native plants and existing trees. Photo courtesy Arterra LLP

There’s a bit of a myth about the drought tolerance, though, that native plants never need irrigation. If it’s a plant from a nursery that’s been raised in a pot, it will take 3 to 5 years to adjust to its permanent home. Once it’s established, it shouldn’t need watering, but before that time, it may need some.

Habitats

We want to create habitats that invite native creatures to come in. But even here, some species are undesirable. No one’s ever asked us for a garden that attracts skunks or raccoons, for example. People have asked specifically for gardens that attract birds, butterflies, or bees. There are specific plants that are good for hummingbirds – they like a deep trumpet flower.

Not all "natural" or "wild" critters are desirable near human dwellings. For example, people love hummingbirds, but very few people want to attract skunks.

Vera: Our “La Jolla de Santa Lucia” project in Carmel took 5 years to build. There were wild turkeys, deer, and even a mountain lion. The client actually sent us a photo of a wild turkey on top of the fountain. We noted the existing deer trails and left them alone, because they’re already in use. Deer paths, once established, can last for a hundred years. One can take the attitude of “this is MY land” and invest in deerproofing so the deer don’t eat the foliage, or one can choose to accommodate the animals that are already there. Animals need passage, food, and also cover. So, for example, we might work around the deer trails that connect new landscaping to mature trees, so that the deer can continue to have access to all these areas without interruption.

Vera: I assigned my students to read the book Chambers of a Memory Palace and then gave them an exercise to describe their earliest memories of a garden. These memories almost always involve animals, not just plants. A lot of memories also involved picking food, or playing with seedpods and burrs from the trees.

Site Stewardship and Resource Conservation

We are always working to educate our clients to the resources of their site and guide them in their stewardship of the land. This includes an understanding of water management, soil preservation and cultivation, tree care and protection, habitat creation, and how the landscape is designed to support passive heating and cooling.

Oftentimes, a site is severely compromised during the course of construction. LEED has acknowledged this and has given a value to conserving a percentage of the site in its natural state. This is certainly the right direction, and it works great on a large site. Even so, much of the land is impacted by construction in one way or another. Site grading, building and road construction, drainage and water conveyance, staging, and parking all change the lay of the land.

We look at the movement of the earth – that’s what construction is, after all – as an opportunity to sculpt the land and create a beautiful building-site connection. If it’s done well, the natural systems already present on the site are restored, and the plant and animal communities can recover.

A rear yard detail from the "Carmel Homestead" landscape project by Arterra LLP, showing the view all around of the pristine natural setting in California's Santa Lucia Preserve. This pool and fire pit could be equally inviting during the evening or at night, too. Photo courtesy Arterra LLP

Water Management

We spend a lot of time designing for the conveyance of water. This is the single biggest resource challenge in designing our modern-day homesteads, and it is here that we collaborate extensively with civil engineers. We prefer to keep these systems visible, in a way that’s integral to the overall design, and we want them to be beautiful as well. However, at the end of the day, the engineers have to make it work and it has to calculate out.

We are often hamstrung by antiquated code requirements and uncooperative building officials. This too becomes a source of inspiration as we figure out creative solutions that can pass muster. Water is so fun and so challenging to work with. It is fascinating to be able to practice at a time when there’s a sea change occurring in people’s understanding about this precious and imperiled resource.

We are actively exploring a full range of options for managing our site water, including water collection, storage and re-use, grey water usage, and methods for slowing or storing water onsite so that it has time to re-charge and seep back into the ground-water table. Green roofs, winter ponds, seasonal creeks, and reduced or water-permeable paving all work towards this end.

Even something as pedestrian as site drainage can have an artful component - and still meet all engineering requirements.

Materials

Earth is of course for soil, grading, and sculpting. Rock and stone. Concrete… we love concrete. Metal, including steel and bronze, for railings, fences and sometimes garden structures. Wood, if it’s sustainably harvested, or if the wood is reclaimed or repurposed. Moorish tile and glass tile. Crushed rock, glass, and porcelain.

The "62 degrees" landscaping project from Arterra LLP was a very site-specific response with a surprisingly varied mix of materials. Photo: Michele Lee Willson Photography

Unit pavers of different sizes and proportions. And of course plantings. In a way, the plantings are just the showiest strand in the weave. A project in Healdsburg that we did together with Feldman Architecture is an example where we mixed materials to achieve an intent. That project has a lot of site walls and grading. Some of those walls we wanted to highlight, while others were needed, but we didn’t want them to show. So for the walls that made a statement, we made them thicker, of concrete. But the other ones had a very thin profile, with rims of steel.

Our material choices are part of the overall strategy which is usually to minimize the hardscape. Instead of a huge hardscape where the entire ground is paved over, we’ll use smaller paved areas with paths between to create a series of interconnected “rooms” surrounded by softscape – i.e, plantings. Sometimes these areas are meant to be used at different times of day. For example, one of our projects has an extended outdoor area including a “living room” with a fire pit, an outdoor kitchen, and a dining area.

For the "Contemporary Update" landscaping project, Arterra LLP created a series of outdoor "rooms". Here we see the living room with the outdoor kitchen behind, and the dining area off at the far corner. Photo: Michele Lee Willson Photography

Working With a Landscape Architect

WHY would someone want to hire a landscape architect?

Vera: It’s the level of attention to detail and the scope of capabilities. We don’t do a hard sell. We just show clients our work and explain the process. If the client doesn’t know why they’ve hired us, it’s not a good match. Sometimes clients know what’s “wrong” with their current site, and they have desires, but they don’t know what to do about it. We start by asking them questions like what do they want to use it for, how they have used similar spaces in the past, whether they’re a sun worshipper or a shade seeker.

Arterra LLP uses various materials in their landscapes. Here we see a bronze detail from their project "The Emerging Garden". Photo: Michele Lee Willson Photography

Our clients come to us with a narrative and a set of ideas. They look to us for an inspired vision and they expect us to deliver a site that is both beautiful AND sustainable. To achieve this, we take inspiration from the client, the architecture, and the mandates of the site. We find that the best design flows gracefully from this effort.

A well-designed garden can double the size of your house, by expanding the usable living space.

That’s true. And some people tell us that they just want to look at their garden, but then they’ll end up using it once it’s there! It invites them in, gives them new ways to use their space. We give the same care to the detailing, to material selection and design proportion, as an architect would for the home’s interior. With careful detailing, we can take that landscape “past the magazines”.

The "Buena Vista" urban landscape design from Arterra LLP. Something about the shape and balance of this pool is very intriguing. Note the screen of ornamental grass, the placement of the seating on either side that extends just slightly beyond the rim edge, and that even the pool rim is not uniform in thickness all the way around. Photo: Michele Lee Willson Photography>

There’s too much CAD. Computers make it easy to just throw in a patio and a fountain. Then they tell us “We already have a hardscape…” but going back to why hire a landscape architect, sometimes people will ask “Civil engineers can do the drainage. Why do we need you?” and we respond with “Well, did you ever drive down a highway and see a beautiful drainage pipe?”

We don’t negate the work of engineers. We work hand in hand with them. A structural engineer can do the job but they won’t necessarily create a striking looking design. They might not think about the impact of using a 12″ or an 18″ retaining wall, for example. General contractors also need to appreciate what we do – we make their work look good! On one project under construction, the client was constantly complaining, until we talked the builder into letting us come in to do the plantings. After that, the place looked a lot more finished. The client was reassured, and calmed down.

When does the landscaping occur during project construction?

Not while the scaffolding is up! Seriously, site grading happens early on. Hardscape and retaining walls come after framing. Finishes and plantings come later. Sometimes the plantings are phased, or are scheduled to occur while equipment is available for other tasks. A large tree might have to be craned in, so it makes sense to do that while the crane is already there. Our collaborative approach continues through construction, as we work with landscape artisans and builders to craft a shared vision. Final plantings occur right before move-in time.

Questions on Style

Do you have any do’s and don’ts for landscape design?

One thing we see a lot is the “one of each” approach. We try first to design to the spirit of the place, but then we let the design percolate until it tells its own story. The creative process should be natural. Sometimes though, it feels forced, because we’re not listening to the site. The engineering problem-solving mentality can lead you to do things that aren’t a good fit for the site. Just because you COULD make something work doesn’t mean that you SHOULD.

Glass tile is another material that Arterra LLP likes to use in their garden design. These tiles are from "The Emerging Garden" and recall the iridescence of Mexican fire opals. Photo: Michele Lee Willson Photography

Another problem is people who see a garden and want an exact replica. They’ll see something in Sunset magazine and say, “I want this garden at my place,” without realizing that the original design was very site-specific. The client has to trust the design process. If you force it to fit, it’ll always feel forced.

What about styles of gardens from different times or cultures?

Historical garden designs are based on local conditions, available materials and technologies, and also on society’s view of humans’ relationship to nature and the cosmos. The French, for example, wanted to control nature – keeping trees that are exactly 8 feet tall, for example. Islamic gardens evolved in arid climates where water was a precious and celebrated resource, and were intended to serve as a wellspring of spiritual repose and replenishment.

Moorish tile is an appropriate material for a Spanish garden, which in turn of course is historically informed by Islamic-inspired designs. This landscaping project is the "La Jolla de Santa Lucia Preserve" by Arterra LLP. Photo courtesy Arterra LLP

How do you deal with landscape maintenance?

Trends now are that clients can’t always maintain an elaborate garden by themselves. So we often design low-maintenance gardens with maybe one area for weekend dabbling. There are also maintenance services that go beyond the typical suburban “mow and blow” operation. Merritt College offers a master gardener program. Another great resource is Bay Friendly Landscaping, a program from StopWaste.org, which offers workshops and training for landscape professionals on environmentally friendly landscaping, addressing conditions specific to the San Francisco Bay Watershed.

Do you have any pet peeves? Things you see all the time that drive you crazy?

Kate: One of my pet peeves involves lawns! All that grass is a waste of water and energy to maintain. Sometimes we have clients who want mostly lawn. They’re often from the East Coast and they grew up that way. They associate grassy lawns with family activities. We might propose alternatives like sport courts or a bocce court. Or a community park – why not go there? This area is so rich in parks and open spaces. But kids play differently now. They’re not outdoors as much, and when they are, they’re much more supervised. Parents can’t let them roam like in the old days, so even when they are allowed to play outside, they’re kept very close to home.

Kate, you did resort design at one point. How’s that different from what you do now?

Resort design is like figuring out a puzzle. You have a certain number of housing units, hotel rooms, holes of golf, Fitness Centers, Retail Zones and other recreation areas to fit onto a designated site. It’s very prescriptive, very manicured, more commercial. And we were working for a developer who is not the end user. With custom work, we can dialogue with the end user and have a lot more impact. Kate was able to see projects to completion over 5 years, but Vera’s resort work was all paper architecture. It wasn’t real, wasn’t tangible.

The "Sunset Idea House" landscaping by Arterra LLP drew a lot of attention from readers who wanted one at their own homes, without realizing that this design was a very specific response to the site. Photo courtesy Arterra LLP

Facing Challenge

We love challenges! Challenges are what make each project unique. We never do things the same way. Every client, every site is different. Challenges are compelling. That’s why we love custom work and figuring out solutions. There are different types of challenges: permitting, neighbors, site.

Sometimes we get large projects that move so fast they’re a design/build, where things are being built while they’re still in conceptual design. That’s challenging, too. We’re wearing many hats all at once: design, cost and budget, then converting conceptual drawings to CAD overnight. There’s a sort of domino effect of implications, trying to remember what’s already been figured out.

Cost

We’re always educating people on what things actually cost. Some people have the wrong idea that landscaping is cheaper than architecture, but we’re using the same materials that you would for a house: tile, stone, wood, metal. The level of construction also matters. People sometimes have a better idea of how this impacts the house in terms of cost per square foot, but they don’t know as much about landscape costs.

The fact that we have a web presence now and so many people can find us on the web brings a lot of traffic, but it’s more casual. In the old days, 95% of our business was word of mouth, and people came to us almost pre-qualified. They had already heard about the cost and the process. Today, not as much. We now spend more time trying to get clarity on their budget expectations before interviewing and taking the time to write a proposal.

The garden by Arterra LLP at the "Sunset Idea House" included a custom-made plant tower, which has a metal latticework frame underneath to hold everything in place. Photo: Thomas J. Storey/Sunset Publishing

Lighting

Lighting design for landscapes focuses on practicality, on getting safely in and out of the house. It’s also for viewing in bad weather or at night. Some of our clients work long hours during the week and the only time they get to see their garden is after dark. We try to highlight key features and spaces. The newer “dark sky” ordinances require shielded light sources and less of it, but lighting is also necessary for safety and security – something the ordinances don’t always take into account.

Arterra LLP give careful thought to lighting in their landscape designs, such as the "Contemporary Update" project. Many clients who work long hours may only get to see their gardens at night, except on the weekends. Photo: Michele Lee Willson Photography

Essential Skills for Landscape Architects

We do a lot of concept drawing by hand. Its quick and you don’t have all these CAD details to get hung up on. Many of our designs are curvilinear and fluid. Of course, technology is here to stay and it’s vital to or practice. The trick is knowing when and how to use it.

When we were hiring about a year ago, we received many applications from highly qualified people. Most of the design programs teach the same set of core computer skills. But what we were looking for most of all was someone who was a creative thinker, a visual thinker. People who had freehand drawings in their portfolio stand out to us more, because we can see how they think. And we know how to guide the process with someone who can draw.

Famous Last Words…

Kate: We love what we do!

Vera: These are extraordinary times to be landscape architects. Everything is changing so fast and for the better good. Each new project is an opportunity to design a beautiful, sustainable garden that include new technologies and the fundamentals of land stewardship I learned as a child. We are so fortunate to be doing meaningful work that we love.

The Architects’ Take | Arterra Landscape Architects

26. Aug, 2011

[…] (link) […]

Landscape Night Lighting Techniques | Lighting Fixtures & Lamps Blog

09. Jan, 2012

[…] For wiring that is exposed, be sure to regularly check the wiring to ensure it has not become compromised or that the casing has not been worn away or chewed off by animals and other pests. Always make replacements immediately to avoid additional damage, such as a fire. Images 1| 2 | 3| 4| 5 […]

Home Decor + Home Lighting Blog » Blog Archive » Landscape Night Lighting Techniques

17. Jan, 2013

[…] For wiring that is exposed, be sure to regularly check the wiring to ensure it has not become compromised or that the casing has not been worn away or chewed off by animals and other pests. Always make replacements immediately to avoid additional damage, such as a fire. Images 1| 2 | 3| 4| 5 […]

Arterra LLP: Adding a Roof Garden to Your Home | Green Compliance Plus - Mark English Architects

19. Jan, 2013

[…] last month, we interviewed the landscape architecture firm Arterra LLP on our sister blog, The Architect’s Take. Kate […]

Arterra Landscape Colorado | amazinggardens

11. Nov, 2015

[…] Arterra LLP Landscape Architect Interview on The Architect … – Interview with Kate Stickley and Vera Gates of Arterra LLP, a San Francisco landscape architecture firm. […]