Building It: An Unheard-Of Housing Strategy

by Rebecca Firestone with Mark English AIA | Interviews

“The whole question about whether developers are greedy is irrelevant. The people leveling this charge aren’t honest. In Los Gatos and Lafayette, professionals making $250K a year are complaining about “greedy developers”. But they themselves are not producing anything tangible, like more housing. They are not contributing to the general welfare…”

– Sonja Trauss, BARF Founder

“Getting evicted is not the worst thing to happen – if you can easily find an equivalent place.”

– Laura Clark, Exective Director, GrowSF

Sonja Trauss is a relative newcomer to the world of housing activism, and she’s saying something totally contrary to what most San Francisco Bay Area housing advocates seem to want. Trauss doesn’t want to stop market-rate housing from being built. She wants MORE housing built, all kinds, lots of it, to address the decades-long housing shortfall that has plagued the Bay Area since the first tech bubble (or maybe even earlier than that). Getting an apartment is more competitive than finding a job, or getting your kid into some exclusive Manhattan preschool, and the process seems woefully similar in some ways. Apparently, even your pet needs its own resume!

Applying for an apartment in San Francisco is harder than scoring that last Rolling Stones concert ticket.

Groups such as the Bay Area Renters Federation (BARF ) GrowSF, and YIMBY aren’t railing against greedy developers, heartless landlords, or even tech millionaires. Trauss is not promoting exclusively affordable housing, either. She is openly blunt about her pro-building stance, and is willing to go to war with suburbs who refuse to build new housing as well as with San Francisco city officials and neighborhood activists who use every method at their disposal to block new housing.

Trauss explained, “YIMBY stands for Yes In My Backyard. It’s the answer to the NIMBYism that’s standing in our way. We want to see more housing built. Any kind of housing. Market-rate, affordable, anything.” Our conversation took place in a garage space on Natoma Street, south of Market in San Francisco. Laura Clark, GrowSF Executive Director, was also present.

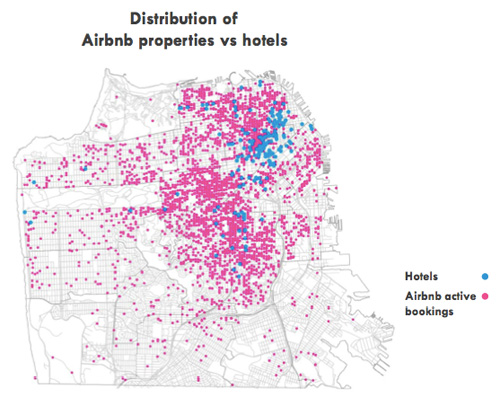

Because it’s so hard to get new housing built in San Francisco, the loss of units to airbnb rentals further erodes availability for those who need a place to live but can’t afford market rents of $3K and up. Image from Forbes.com

Most of the narrative is from Sonja Trauss. In a few places, I’ve inserted remarks in [angle brackets] for items where I might have added something that she didn’t say herself, to add a conversational aside, clarify something, or in a few cases to register an alternate opinion without taking away from the main thrust of Trauss’ arguments.

It’s the Google Bus Again

So, what did you think about that Tech Crunch article “How Burrowing Owls Led to Vomiting Anarchists (Or SF’s Housing Crisis Explained)” as an accurate breakdown? Do you agree with its presentation of the facts?

Sonja Trauss: Yes! That article was foundational. It provided details and a specific narrative that were convincing to me and legions of other readers. The Bay Area has a straightforward answer, which is to build more housing. We finally said, “Don’t just complain about things on message boards.”

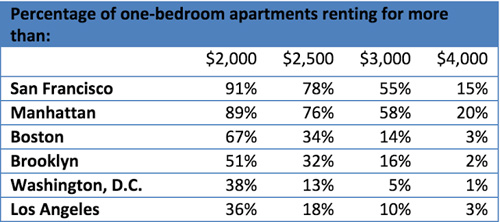

[the above graphs are from a recent Economic Policy Journal entry.]

Laura Clark: It’s such a crazy problem, which should be obvious to solve. Why isn’t it solved yet? When I first moved out here, as a native of the Washington, D.C. area, I was just incredulous… are people really that stupid? Out here, the so-called progressives were actually leading the charge, against new housing.

Greedy Landlords Are Not the Problem

What do you think about the charges about greedy landlords, or greedy developers? How much profit is OK, really?

Sonja Trauss: The whole question is irrelevant. It’s just rhetoric. No other product gets this kind of scrutiny. Are farmers greedy? Clothing retailers? The people leveling this charge aren’t honest. In Los Gatos and Lafayette, professionals making $250K a year are complaining about “greedy developers”. But they themselves are not producing anything tangible, like more housing. They are not contributing to the general welfare.

The people who say “We need to protect communities” are really saying “We want to protect our property values”. They don’t really care about profit margins. As Tim Redmond, former editor of the San Francisco Bay Guardian says, “We want people to go somewhere else”.

[The above image is from a post titled “Know Your NIMBYs” which skewers almost every San Francisco progressive archetype.]

Sonja Trauss: The only time the public concerns itself with profit margins is regarding finance people – but it’s only because we bailed them out! Is Wal-Mart greedy? Well, the public subsidizes the Wal-Mart workers, because Wal-Mart doesn’t pay them enough. That’s a labor issue.

Developers aren’t monolithic. A small number of them are multimillionaires. A few more of them make something like $250K a year. And some are broke, gone bankrupt.

Laura Clark: We should not base our public policy on what is in people’s hearts and minds, judging them as greedy or whatever. We should base our public policies on creating new housing any way we can.

Proposition M

[Trauss brought up Proposition M, which limits the amount of new office space that San Francisco can build every year. This has led to discussions about increasing the jobs-housing linkage fee that developers pay in order to offset the new office space.]

Laura Clark: But it doesn’t matter how many fees the developers pay, or whether proposed housing is earmarked as “affordable housing”, if any multi-unit housing project takes 5 years to get approved due to NIMBYism.

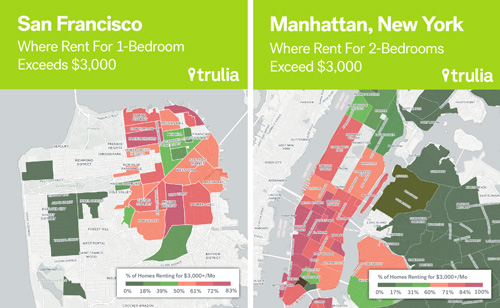

San Francisco rentals are officially more expensive than Manahattan now. A 1-bedroom costs $3K here. In Manhattan, you can get a 2-bedroom for that same price. Images from Trulia.com

Sonja Trauss: In the past 5 years, 300,000 people have moved to San Francisco and 250,000 people have moved out. That’s a net gain of 50,000 people. Considering that 1 housing unit can accommodate around 2.3 people on average, those people still need 21,739 units of housing somehow.

Median Housing Price

One argument put forth against new market-rate housing is that it won’t lower the median price of housing.

Sonja Trauss: Building more housing might or might not lower the median price, but even if it doesn’t, that’s OK. The median price can stay the same, because more housing means more units below the median, too.

Laura Clark: Also, people do better in cities than in some post-industrial sprawl, or in rural isolation. It’s greener, too, because you don’t need a car to get around. There’s more services. People can age in place more easily than if they’re isolated. We WANT people to live in cities – so why are we pulling up the drawbridge?

We Need A Politically Unified Region

Are you focused purely on San Francisco, or do you care about the surrounding regions too?

Sonja Trauss: We focus on the entire Bay Area. We sued Lafayette and are considering suing Los Gatos. Lafayette had approved a multi-unit housing and then people said it was too much, so they scaled it way back.

The real problem is a lack of unification. New York City is politically unified, whereas we are fractured into fiefdoms, a hundred cities all making their own land-use decisions. Some regional entities exist, but they can’t really enforce any sort of regional plan.

So how do we get there?

Sonja Trauss: By creating state-level laws that everyone has to follow. Sometimes even small steps are good. For example, we recently passed a parcel tax to clean up the wetlands as the first ever regional parcel tax. It’s telling that Tim Redmond, the Bay Guardian, and libertarians all opposed this tax.

Because establishing a regional tax is going down a slippery slope?

Yes, they claim that it’s leading us straight into the arms of Big Government.

Other Regions

So, when did New York actually unify its boroughs?

Sonja Trauss: In the 1850s, the U.S. had a nationwide trend, a super-trend, of townships incorporating themselves into larger regions. New York City [1898] , Philadelphia [1854], and Oakland [1854] all did it. It wasn’t hostile – they WANTED to do it. In Oakland, a few areas like Piedmont held out and that was OK.

We’ve lost a sense of forward progress. Here, progressives are actually conservatives, fighting change. But why are we nostalgic for the 1970s and 80s? San Francisco’s population declined until the mid 70s.

Defining Success

How would you define a successful housing project?

Sonja Trauss: If there are people living in it. The crash of 2008 saw two types of failure:

- In West Oakland, the Pacific Cannery Lofts was a loft-condo conversion. The developer lost a lot of money, but from another standpoint it was a success, because people are living in it now.

- Empty subdivisions near places like Las Vegas. Nobody wants to live there.

How will you know that you have succeeded in your mission to create enough new housing?

Laura Clark: We can’t stop all evictions or prevent home loss due to fire or other circumstances.

- Success is when getting evicted is not the worst thing that can happen, because you can move to an equivalent place.

- Or, when market-rate housing can compete with subsidized housing. With subsidized housing there are lotteries and wait lists. With more housing available, people could opt for something more expensive but still within their reach, if they didn’t want to wait.

- Getting evicted is not the same thing as displacement. Displacement happens when you get evicted and re-housing isn’t even possible.

Renters in San Francisco can be evicted for reasons beyond their control, including owner move-in or building sale – a disaster in a city where a 1bedroom, market-rate, rents at $3000 a month.

[I think of success as being in a place you really want to live in.]

Sonja Trauss: People have different preferences. There’s no one type of housing that will work for everyone. For example, I don’t want a yard. Too much work! People want yards for gardening. But other people want their own private patch, for their own use, or as a personal success symbol.

Yards are built into zoning, if you can’t build to the property line. In Philadelphia a typical property layout is 80% lot coverage and then a concrete paved side yard for the trash and other outdoor stuff – bikes, sleds, wet boots.

But It’ll Be Ugly

A lot of discretionary review defenders are concerned with aesthetics. They’re afraid that open season would mean too many cookie cutter buildings or hastily constructed shoebox dwellings.

Laura Clark: I’m sick of hearing the “but it’s ugly” argument against building new housing. Who knows what people a hundred years from now will like? If we want to regulate “beauty”, let’s activate the first-story retail. That first story engages with people and draws them in.

[This is the same thing David Baker is saying about the Q Zone.]

Engaging with pedestrians at the ground level is more important than regulating aesthetics in an abstract sense. Image from Smartgrowth.org

[Above image from “Strategies for Good Urban Retail”, which has detailed recommendations for re-inventing a vibrant street life, including good examples of Do’s and Don’ts.]

Sonja Trauss: Regulations should be changed to increase flexibility. You can change building aesthetics pretty easily without changing the building itself [different finishes, colors, or “skins”]. More flexibility would enable easier renovations, and flexible uses are better for re-purposing.

Zoning for flexible use might influence floor plans, building width. Office buildings aren’t required to have natural light, but dwellings are. If an office building were designed for natural light, it could be re-purposed into living spaces if the tech company goes out of business.

Laura Clark: We wouldn’t need that “Twitter tax break” if their building were potentially convertible to housing.

King for a Day

This is a fantasy question. What would you do if you could be king for a day, or wave a magic wand and transform the world to satisfy your dearest wish? What might the Bay Area look like if you could have your way?

Sonja Trauss: When I came out here from Philadelphia, where I grew up, I thought San Francisco would be like Manhattan West: diversity of culture, industry, people, and arts. I found instead that San Francisco is NOT a world class city – too expensive, not enough culture – except for circus culture.

The New Yorker magazine has many pages of listings for plays, art-house films, and other events in New York City. And they’re not all protest plays, either.

Laura Clark: Artists are hurt by the lack of housing. Like everyone, their rents are too high. The market for art is generally people with disposable income. There are wealthy people out here, tech types who are willing spend money on plays and art – just look at Burning Man. But artists struggle to reach their market here. They are priced out, displaced, and unable to bring their wares to market.

Sonja Trauss: Here are some things that would be nice to see:

- Rebuild the Sutro Baths, and have a subway running along Geary out to the beach.

- Build high-rises down at the ocean – it’s more democratic. Everyone should enjoy the ocean views.

- The agencies that make up the various transit authorities should talk to each other more.

- Eliminate density restrictions in zoning.

- We need a fully politically integrated Bay Area, including Marin and Oakland.

- More rooftop public space.

- Build up higher. Much higher.

Laura Clark: It’s useless to rail against the “tech millionaires” as obnoxious and self-centered. Stifling the economy will not get rid of obnoxious people. We have to engage with them and socialize them to be less obnoxious. Super mixed income neighborhoods are good. They foster engagement with a broader spectrum of diverse people. It’s also good because then you can’t ignore poverty.

My dream is that it should be equally viable to use public transit as it is to drive anywhere.

Omelettes and Eggs

There’s an expression saying “You can’t make an omelette without breaking eggs.” So, consider other sweeping municipal changes over the past few hundred years. Those wonderful Parisian boulevards displaced a whole lot of people. In other cities around the world, neighborhoods have been razed and the people simply driven out. So, how are we going to make major changes without harming anyone? Whose eggs are going to get broken?

Sonja Trauss: That’s eminent domain, which is government stealing land.

Laura Clark: We don’t need to raze the Painted Ladies. We have to realize, however, that historic preservation also has a human cost.

[Yes, there are corrugated shacks that are considered “historic” because they were used in WWII shipbuilding.]

Friendlier High-Rises

What message do you want to send to our readers on The Architects’ Take?

Sonja Trauss: I feel bad for the architects. They don’t want to hear about “ugly” buildings. I’m OK with more ugly, because more houses could also mean also a greater number of distinctive houses as well.

One critique of high-rises is that they function as gated communities. There’s no reason why we can’t change that. We can design high-rises differently, so that parks and shops are integrated within the building itself, which is more open to the public.

This architectural rendering shows what a “vertical village” might look like as a friendlier alternative to the more familiar “gated community” high-rise. Image from Designbuild Network

[There’s a good description of the “vertical village” concept on the Designbuild Network, which is the source of the above image.]

Residents will have to accept a new norm, where public space starts at their front door, their apartment door – not at the front doors of the apartment building. Buildings could have wider hallways, outdoor walkways, and the apartment doors should be sturdier, thicker. Not cheap and flimsy interior doors.

More public gathering space could be integrated within and also between buildings, including retail. Design the building so that it feels normal and safe to have the building publicly accessible for retail.

[A shading spectrum of public to private space]

Defensible Space is the Wrong Approach

There’s a tension between philosophies such as Defensible Space, vs the new urbanism that wants more public space and more inclusiveness. William H. Whyte’s book on the social life of small urban spaces says as much, that if you design defensively, you’ll get exactly what you DON’T want, but if public spaces are more welcoming, everyone will use them and the spaces will be a lot nicer to spend time in.

Sonja Trauss: Oscar Newman’s “Defensible Space” was based on a faulty premise. It was created in response to security issues in public housing, as if designing certain features could reduce crime. But those housing projects failed due to underfunding. There wasn’t money available from Federal, state, or local governments to do ordinary maintenance. Newman said that better design was the solution, but design won’t solve funding issues. You still have to maintain it.

Sonja Trauss will be a panelist on a forum September 22, 6-8 as part of the Architecture in the City Festival. Tickets available at archandcity | Lectures

One Response to “Building It: An Unheard-Of Housing Strategy”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Craig Hamburg | The Architects' Take

18. Oct, 2016

[…] Tiny House advocate David Ludwig, affordable housing architect David Baker, housing advocate Sonja Trauss, architect Anne Fougeron, FAIA, City Planner David Winslow, as well as Craig Hamburg, who has […]