Michelle Kaufmann: Phoenix Rising

by Rebecca Firestone with Mark English AIA | Interviews

“My husband and I were looking for a place to live and all we could find was crap! We couldn’t afford anything well-designed, well-made, and energy-efficient. After seeing the thoughtless crap that was filling the landscape, we painfully decided to do something about it.

“We got a bit of property and built a little “green” house on it. Then we thought about the possibilities for mass production, and said, YES! Now, there’s no “if” when it comes to green, healthy, efficient homes. And they can be well-designed and affordable. It’s in how you make spaces, views, and light. The space should feel big, but you don’t have to build it big.”

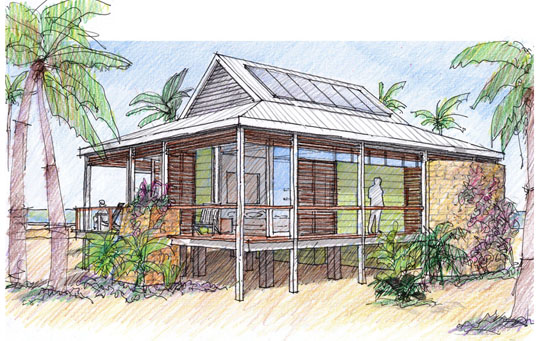

(Photo: Sunset Breezehouse, designed and photographed by Michelle Kaufmann)

Five years ago, Michelle Kaufmann was the darling of the architectural world for her ingenious, architect-designed pre-fabricated housing systems. The housing market couldn’t have been better, and demand for both affordability and design quality seemed like a match made in heaven. Awards and kudos came from all sides. They had a factory all geared up and ready. It couldn’t fail.

But of course it did, along with the global economy. Kaufmann and her business saw factory partners close their doors, home mortgage lenders melt down, and the housing market collapse. What does an award-winning architect do when it all collapses? If success is the indicator of good design, what does it mean when someone who was top of the heap yesterday is back at Square 1 today, along with all the rest of us? Well, for one thing, it means welcome to the club, since it’s almost fashionable to go bankrupt and lose your home, walk away from it even… or so the news media says.

Michelle Kaufmann is willing to take big chances, because any culture of innovation must accept risk. In some countries, innovation is either punished or actively discouraged, beginning with a child’s first day at school. But in this land of opportunity we can conceive and act; we have more freedom to experiment, and we have the freedom to fail as well. One indicator of “failure” might be going bankrupt – but every entrepeneur knows that not every venture succeeds, and it doesn’t reflect poorly on them to have tried something new. In more cautious cultures, a bankruptcy equals a total loss of reputation, but in today’s world, it’s the recovery that’s important.

Today, her company Michelle Kaufmann Studio is alive and well, with new projects and new work including two interesting projects of a distinctly spiritual bent: the New Camaldoli Hermitage in Big Sur, California and an 8-unit multifamily modular home project in Denver, CO for the Sisters of St Francis. Her design offerings also include four prefab single-family home models that, in photos at least, are indistinguishable from the best custom-designed architecture that one can find. (If they don’t become collector’s pieces within 20 years, I’ll eat my hats. All of them.)

In fact, buyers can have the best of both worlds, choosing either preconfigured or custom-designed homes that are one-of-a-kind, but still built using prefab techniques and technologies. Costs and timeframes are competitive with other designer homes built by the “old-school” methods of framing and assembly onsite.

An instance of Michelle Kaufmann's "mkBreeze" prefabricated home design was shown in Chicago last year.

In addition, Kaufmann is intimately involved with Architecture for Humanity, a San Francisco-based group that rebuilds after disasters around the world, from New Orleans to Sri Lanka. Her contributions apart from design include tireless efforts to promote practical ecological solutions in areas such as rainwater management, and a fascinating and altruistic blog, where she often spends more time promoting other people’s work than her own.

Kaufmann combines several forms of genius, actually, but first and foremost are her design sense and her willingness to delve deep into manufacturing processes in order to re-invent, re-engineer, and re-think. That, along with unquenchable optimism, endless fortitude, and an amazing generosity of spirit, make her an extraordinary force for change – a force of nature, one might say, akin to the earth-goddesses of old who were, in fact, guardians of the hearth and also of agriculture. After all, shelter is one of our most basic human needs for survival, and to honor the “sustaining” of life in all its dimensions is one of the oldest of human ideals.

In the interview, three voices are represented: Michelle Kaufmann, Mark English (ME) and Rebecca Firestone (RF). Content excerpted from other interviews appears within as italics, including a few portions of a longer interview with Treehugger.

ME: What’s your story? How did you get here?

Kaufmann: My first job out of grad school was working for Frank Gehry. I loved it. For 5 years I focused almost entirely on museums. It was interesting to see people walk into museums for the first time. At the Bilbao opening, I saw people weeping openly when they went in, because the space moved them so much.

And then, at the other end of the spectrum, my husband and I were looking for a place to live and all we could find was crap! Of all the homes out there, I think only 3% are truly designed, by actual designers. We couldn’t afford what we wanted, which was something well-designed, well-made, and energy-efficient. I was also chemically sensitive and was very concerned with indoor air quality and mold. So after seeing the thoughtless crap that was filling the landscape, we painfully decided to do something about it.

Only a small percentage of homes are created by designers who care about creating really good designs. Shown is the MkSolaire design by Michelle Kaufmann, an urban row house that uses non-toxic, renewable materials and ingenious design to coax light and air deep within the interior.

I had not been familiar with the term “green building” until my husband, Kevin, and I began looking for a home for ourselves. Our key goals were to find a home that was well-designed, clean space without visual clutter, that would have low energy bills, healthy air quality, low-maintenance materials that aren’t killing the rainforests or increasing carbon dioxide, and could fit in our budget. Gulp. Our budget didn’t even make it on the low end of what was available unless you count “tear-downs” – which we could almost afford, but then we couldn’t afford to build anything after that. A home with these characteristics did not exist on the Bay Area market.

We spent a painful 6 months attending every open house we could find. Every Sunday, every Tuesday, I would make a plan for Kevin and I to follow to visit 5 or so homes in a 4-hour period. Each morning as I laid out the plan, I remained unrealisticially optimistic. Surely today would be the day we would find our home. At end of each day, Kevin and I would recap our findings. It usually included me finding excuses for why the home that required walking through a bathroom to get to the bedroom, and smelled like the curry aroma would never leave no matter how many cleanings, could actually work for us. I was getting wrapped up in the frenzy. We have to move fast, or this opportunity won’t last!

One instance of Michelle Kaufmann's mkBreeze design, located in Dry Creek. Photo: John Swain Photography

Clearly, I was emotionally invested in us finding a home, and logical thinking had evaporated as quickly as the homes were leaving the market. Luckily, Kevin was able to remain logical and helped me see that even if we thought we could live with the curry smell – even then, a kitchen with pink tiles, and single-pane windows that somehow allowed the breezes to be felt in the room even when the windows were closed, even that was still above our price range. How could this be?

After a few months of these days of emotion and denial of reality, we entered into couples therapy. What have we done so wrong in our lives that we cannot afford a clean, green home to live in? Where did we go wrong? What decisions did we make that have brought us to this painful state?

A second instance of the same mkBreeze design shows that even a repeatable design doesn't have to be identical in execution. Photo: John Swain Photography

We finally realized what we wanted simply did not exist. When I first embarked on this journey, I wasn’t thinking like an architect. I was just another renter in search of a decent home to buy. As an average, middle-class professional in the San Francisco Bay Area, I assumed that with enough patience and searching, I would be able to find a modest, affordable home. Was I ever wrong!

After walking through a seemingly endless array of overpriced, uninspiring houses, I began to realize that the architecture profession had largely overlooked the needs of the average aspiring homeowner like me. Architect-designed, personalized homes can be miniature masterpieces, of course, but they are rarely affordable for anyone but the most affluent. As well, most architecture firms focus their energies on designing skyscrapers, museums, and other civic structures; thus the job of creating functional, well-designed housing for average families has largely become the business of the building industry. Although the industry has done a good job of meeting consumer demand, these homes, which are often large and poorly designed, are not always beautiful and inspiring.

We decided to build something for ourselves. I was an architect, and Kevin, a builder. So it seemed like a reasonable option. Luckily for us, we were naïve to not realize the challenges that lay ahead. We were also under the impression that Kevin’s experience in cabinet, furniture, and stair making would not be so different than building a whole house.

We looked for land, and found a lot within the first week. We worked together to design a home that was the right size for the two of us and our two dogs, that embraced the outdoors, and that collaborated with the landscape. Kevin challenged me on every decision, always questioning and pushing for solutions that used the least amount of resources from the earth in terms of our the materials were made, and/or how they were to be maintained over time. We designed the house not for how it looked, but how it felt. We designed it to have a zero electric bill (through the use of PV solar panels). We designed it to use less (less water, less energy, less materials). We designed the home with a series of sliding glass doors, sliding wood panels, and sliding wood sunshades. Kevin, always thinking about the home sitting lightly on the earth, kept referring to them as “gliding” doors and panels. He jokingly started referring to our house as the “Glidehouse”. The name just stuck.

The next few photos show three built interiors stemming from same design as before - Michelle Kaufmann's mkBreeze - same three built instances. Photo: John Swain Photography

In the end, we have a home that we love that did accomplish all of our initial goals. However, it was not easy. It took a lot of time and a lot of energy.

After going through the process, I realized something extremely important. I realized that my earlier thinking that I, as one person, could not make a difference was simply not true. That thinking was lazy and made it easier for me to consume without consideration or thought. Each person has so many choices, each day, that can result in a lot less usage, and a lot less waste. In combination, each person can make a difference.

Aside from interior furnishings, another differentiator is of course site orientation, which in turn may affect how the interiors receive natural light. Photo: John Swain Photography

What I have found in the past years since building our home is that there a lot of people who feel the same way that Kevin and I did. They want green homes, they want lower energy bills, they want healthy environments for their families, they care about the environment and their children’s future. However, it is not always easy to find the solutions.

In fact, while we were building our house, we had friends and colleagues who asked if I could do a house for them. They wanted “clean and green” homes as well. (They too had been going to the open houses, not finding solutions, and were contemplating therapy.) This raised an interesting question. Could we make our Glidehouse in mass production?

I had been becoming increasingly aware of prefabricated construction. Through her work with Dwell magazine and her book written with co-author Bryan Burkart, Allison Arieff had seemingly single-handedly made “Prefab” a word that embodied the goal of making good design for the masses. Allison spearheaded the Dwell Home competition, which demonstrated the varied ways prefab could be well-designed, beautiful and sustainable. After decades of being viewed as substandard, white-trash, and trailerhomes, “prefab” was now high-design.

Same house design as before, but each built instance still has unique touches that reflect the owner's choices and desires. Photo: John Swain Photography

Also, before we started building our house, my friend Ryan Stevens talked to me about prefabrication. It was kind of the like the scene in the movie, “the Graduate” when the word “Plastics” is whispered in Dustin Hoffman’s ear, as though it were the answer to his entire future. Ryan did the same with me. As my head was lying on the bar counter in exasperation, as I was recounting my lateset frustrations with looking for a house, Ryan whispered, “Prefab. You should look into it. Maybe that is your answer.”

In fact, the home Kevin and I built for ourselves was prefabricated in a small way. We used SIPS (structural insulated panel system) for the walls, floors and roofs. These panels had been precision cut offsite, and shipped to our site on a truck. The literature on the SIPS panels had promised less time, less money, and higher insulation value. While the insulation was more energy-efficient than typical insulation options, the use of these panels for our home did not cost less or take less time. However, this may be a different story if they are used in mass production.

As I thought about the idea of making our house in mass production, I started looking into different prefabrication techniques. I found that modular factories existed, and have the potential for high-quality design, with precision cutting, less waste, increased quality control with less time than the equivalent site built. This answered my question. Yes, we could make our house in mass production. And, in doing so, we can significantly reduce waste, maximize material efficiency, and save on oil usage. We could offer our design, so others can have a more accessible green home, without having to go through the painful process that my husband and I had to.

I then started Michelle Kaufmann Designs as an architectural practice specializing only in green, modular designs, all working toward the goal of making thoughtful, sustainable design that is accessible to all. Sustainable, healthy living should be for everyone. It shouldn’t just be for the wealthy, or for hard-core environmentalists.

Things happened REALLY fast after that, it really exploded. This was in 2003. It requires scale, but now there’s no “if” when it comes to green, healthy, efficient homes. Everyone wants that nowadays.

Even a mass-produced home can achieve a sense of interior spaciousness and scale - if the designer is Michelle Kaufmann. Shown here is Kaufmann's mkLotus prefab home design.

ME: There’s a perception that green and prefab are mutually exclusive, that prefab can’t be green. And there’s a perception that neither can be beautiful, except at a high premium.

Early on, I made it my goal to marry good design with minimal environmental impact to create “green” homes that would be available to everyone. To do this, I had to create an uncomplicated system that would use the principles of mass production to blend sustainable home layouts, eco-friendly materials, and low-energy options to create a “prepackaged” green solution to home design. A few architect friends of mine expressed skepticism about the viability of such a mass-production endeavor. As they pointed out, many architects before me had tried, some more successfully than others, to design prefab structures for the masses.

Compare the kitchens in this photo and the next two. The same three built instances of Michelle Kaufmann's mkBreeze design are shown. Photo: John Swain Photography

Others warned that promoting design for the masses might lead other architects to view me as “selling out.” But I strongly believe that architecture is a service, one that shouldn’t be available only to the wealthy or highly educated. Good design can and should make life better and more beautiful for everyone.

I soon realized that I would have to start thinking less like an architect and more like a product designer. As I began researching the history of mass production and product design, I was delighted to realize that I was following in the footsteps of other architects who had successfully created great design for minimal cost, largely by making use of standardized parts.

These kitchens are a good test of basic spatial design. We don't need finishes to "rescue" an awkward space if that space is well-planned to begin with. Photo: John Swain Photography

Charles and Ray Eames, for example, the legendary American designers in the 1940s-1970s, were best known for their work in architecture, furniture design, industrial design, and manufacturing. The Eameses’ unique vision was to bring “the good life” to the general public through modern materials, new technologies, and high-quality design. To do this, they promoted mass production of their furniture and architectural elements. Their groundbreaking work included the iconic Eames Chair and their Case Study House in Pacific Palisades, California – widely considered to be one of the most important post-war residences ever built. I was greatly encouraged by their firm belief that design – big or small – could improve people’s lives.

Minor details like the corner windows also provide variation in this third built instance of Michelle Kaufmann's mkBreeze design. Photo: John Swain Photography

I explored the work of Joseph Eichler, a revolutionary developer from the 1950s, who redefined suburbia by teaming up with architects such as Quincy Jones to create affordable, progressive home designs. Between 1949 and 1974, Eichler built 11,000 unique homes using mainly prefab parts, providing much-needed housing for the 1950s middle class. Today, Eichler’s pioneering homes are still beautiful, modern, enduring masterpieces. With efficient, open floor plans and light-filled atriums, the homes feel as fresh and innovative today as they did 50 years ago.

I also drew inspiration from the work of my mentors Michael Graves and Frank Gehry, two of contemporary architecture’s most remarkable practitioners. Although best known for their stunning building designs, both Graves and Gehry are also product designers. Michael Graves was one of the first contemporary architects to venture beyond the realm of building design into product design. The teakettle he designed for Alessi, a playful and beautiful recreation of the standard kitchen kettle, quickly became a modern icon and quieted the criticism of other architects who had cynically predicted failure for his product designs.

This custom home designed by Michelle Kaufmann uses the same systems and modular spatial thinking as the prefab versions. Photo: John Swain Photography

Today Graves has branched out to design home furnishings, jewelry, and dinnerware for companies such as Disney, Steuben, Phillips Electronics, and Black & Decker. Most recently, he teamed up with Target retail stores to create 100 beautiful, affordable products that remain some of the store’s most popular housewares. Frank Gehry’s signature, sinuous style of architecture can also be found in objects other than his buildings. He has designed six different lines of jewelry for Tiffany & Co., and has worked with other companies, including Alessi, to design furniture, light fixtures, and housewares.

The adjustable shading shown on this custom home from Michelle Kaufmann helps to control daylight and heat gain, and is a common feature in many of her other designs. John Swain Photography

RF: Can prefab really be profitable to build, AND beautiful, too?

Although prefabrication and mass production can save time and sometimes money, it has to be intelligent and thoughtful. No one wants to live in a generic box of a house that fails to respect a particular site’s climate or orientation. I recognize the importance of working closely with clients to create a home that is uniquely in harmony with its surroundings. Our homes need to meet the individual needs of the people who live in them. This is the kind of architecture that energizes me — homes that are economical to build and operate, that serve the people who live in them, and that don’t take too much from the earth.

ME: Has there been any industrial push-back? Lennar Homes and the other big guys – aren’t those tract home developers already doing prefab, in a sense?

Kaufmann: There are a lot of prefabricated components in their homes (roof truss systems, panels, etc.). They just don’t promote it that way.

RF: They’d have to change some of their ways to be sustainable, though. They’d have to consider the full building life cycle more carefully.

Kaufmann on Treehugger: Knowing that our needs and desires change over time, we can design for efficient deconstruction (rather than demolition) resulting in zero waste. For example, currently, if one remodels their kitchen most of the countertops, cabinets and plumbing fixtures are ruined with the removal because of typical construction techniques and how they were originally constructed. However, if we design and build an entire kitchen module that could be removed (floors, walls, mechanical systems and all) and a new kitchen module inserted, the old kitchen stays intact and can be reused by someone else with no waste produced.

ME: What else are you working on now?

Kaufmann: A resort in the Caribbean that’s being fabricated in South Carolina. It’ll be a Net Zero project.

Michelle Kaufmann is currently working on a Net Zero Energy resort for Orbitz Travel, to be located in the Bahamas, using all renewable-energy systems.

A very recent community project shows where I think prefab is REALLY headed. Casa Chiara is a multi-family dwelling for the Sisters of St. Francis, and it’s one of the first multi-family, modular, sustainable projects built in the U.S.

Casa Chiara, designed by Michelle Kaufmann, is a sustainable multi-family dwelling using a prefab, modular building design/build approach.

Now is really the time for companies with this technology, where there’s a need for good housing and fast. Places like Haiti as a matter of fact, that need disaster aid including housing. But not temporary housing! Temporary housing, like those FEMA trailers, is unhealthy and disposable, not sustainable.

In addition to Casa Chiara, I’m working on a community right now in Denver called AriaDenver. We just completed the first phase of 8 homes. There will be 106 homes in total, some affordable, some market rate, and some co-housing. The intent is to design it to be multi-generational, and take the best parts of the co-housing to use as design criteria for the entire community.

ME: Did you do anything in Louisiana following Katrina?

Kaufmann: No, I had to stick to California at that point.

Transporting and assembling prefab housing can be quite an adventure. Michelle Kaufmann's mkBreeze home design goes together in large chunks onsite, saving labor and time.

ME: How did you get from Gehry’s office, with its monumental civic architecture, to doing prefabricated private homes?

Kaufmann: My experience as a user drove me to it, when I couldn’t afford a place to live. I said to myself, “This is WRONG! What can I do to have as much impact, bring good design back to the masses?”

Homes like this one are for sale in towns all over the Bay Area. Generally, the interior spaces aren't optimized; they don't flow as well and there never seems to be enough room where you want it, and too much in other spots where it's wasted.

When my husband Kevin and I decided to build our own house, we wanted it to be healthy with no mold (as I was getting migraines in our apartment in Sausalito and we found it was because there was mold in the walls); we wanted no energy bills (we were and are on a budget); we wanted low water bills (that budget thing again); we didn’t have a lot of money so we couldn’t build a big house but still wanted it to feel spacious; I thrive on natural light, so I wanted the house to use natural light in a smart way so we wouldn’t have to turn on lights during the day. Kevin wanted to make sure we chose materials that would last a long time with little maintenance.

In the end, all of our qualifications defined a green home. But it was before the term “green” was being used. And definitely before green was cool. My mother used to call many of the green design elements “being frugal” when I was growing up.

ME: In residential work, even for the masses, you really have to love your clients. You have to care.

Kaufmann: It’s very intimate.

Even a prefab home like the mkBreeze can create intimate social space. Photo: John Swain Photography

Kaufmann: I do love my clients, and I care about them deeply. That is what drives me to not want to give up on the idea. So many wonderful clients invested in this idea of prefabrication and accessible, thoughtful design. So I won’t give up on that.

Another interior treatment from one of Michelle Kaufmann's mkBreeze projects. Photo: John Swain Photography

ME: How many of these projects actually got built? What sort of person was your typical buyer?

Kaufmann: 54 to date. Our clients are a pretty diverse group. All over the map, really, regarding age, ethnicity, and finances. However, there are some common characteristics: they are all really smart, many of them related to the design or technology professions, and almost all of them listen to NPR. A good proportion were travelers – maybe that adventurousness attracted them to this new type of housing. Turns out that is also one of the best descriptions for my ideal friends in life too.

ME: Within your method, do you see a conflict between personal-scale and commodity-scale building?

Kaufmann: You have to set up a network, do something grass-roots as a proof of concept. Grass roots first, then scale it up. An example of that is Yvon Chouinard, the founder of Patagonia sportswear [working with Wal-Mart on end-to-end supply-chain sustainability]. He was grass roots, they were the scale. There’s a moment in time when those priorities align.

ME: How do you reach your audience with your message?

Architects have gotten too far from the mainstream. They don’t re-think it, don’t reach out. There are tools now that educate people on good design. Even my grandma watches design shows on TV! Of course she’s getting a lot of crappy information. But there’s some good content, too.

The Slow Home movement is attempting to wean the American public from their "individually wrapped lives" and tract-home communities that look like "17,500 fast food meals to go"

ME: There’s a sense of openness right now that I didn’t used to have in my practice. Was it the critique system in school that taught everyone to hoard their ideas?

Kaufmann: We made some critical decisions early on with our web site, to create a hybrid that combined both architectural design and work product. We had tools for people to make their own decisions. We tried to make it as transparent as possible. Some of our clients hadn’t worked with an architect before. Were we giving our game away? Maybe, but we decided to be transparent, to be open. A key part of the work was just putting it out there, and helping others to build this way successfully. The more of us that are doing it well, the better.

Almost every other design-oriented architect wants to retain intellectual copyrights to their designs, but Michelle Kaufmann decided to allow people free use of her designs. Note the background; the example here stood outside Chicago's City Hall for several months as a demonstration of sustainable design.

Kaufmann on Treehugger: Some of the most interesting work being done is through collaboration of different disciplines. Imagine a design team comprised of a molecular biologist, a farmer, a building automation specialist as well as an architect. The focused intensity of all these individuals, who might not normally be in the same room together, could be apt to ignite some truly amazing and innovative solutions to current day problems.

ME: You can’t hoard information anymore, not with the Internet. But here’s a question I always ask people. What do you think about Dwell magazine? A lot of people have strong feelings about it.

Kaufmann: Today, we can be stronger by building networks and by sharing information. We shouldn’t fear it anymore. Dwell makes people feel empowered. They totally cracked open the idea of accessible modern design for the masses. They really supported the idea of prefab, too, so I’m very thankful.

ME: Print magazines are fading away.

Kaufmann: Dwell will survive. They went online early.

ME: What are some of the limitations of prefab?

Kaufmann: It changes where you feed your creative soul. It used to be we’d create one-off homes where every detail was unique. But with prefab, you can get super-strategic in other ways. It’s like designing a home version of the iPhone: making a well-designed model for mass-production, but also allowing for a slew of personalization.

Prefab designer housing can be more appealing if it's "customizable" just like an iPhone. But not too customizable. This instance of the mkSolaire house was shown in Chicago last year, along with the mkLotus shown earlier.

RF: There’s an idea, “hackable” homes. What latitude do you have with prefab for customization?

Kaufmann: That depends: where does your business plan lie? We offered preconfigured designs, four plans all with the same roof plan and same structural system. But, there are limits to what you can customize. It’s like going to an auto dealer and saying, “Well, I want a Prius, but I’d like it to have 2 inches extra leg room in the back seat.”

Preconfigured homes are like cars - you can't just take a Prius and make it 2 inches longer in the back.

You can’t do that with a car, and you can’t do it with prefab either. You can’t make the kitchen two feet longer or the roof two feet higher. Eventually, we realized that we had two categories: preconfigured, and custom. The custom stuff was still built in the factory, so even though they were one-off designs, there was less waste.

ME: What about other home kit companies? Are they a series of details, materials, and systems, or are they a kit of parts like erector sets?

[One example is The Acorn Deck House Company]

Kaufmann: You need healthy constraints, but you have to think of them in more thoughtful ways.

"The space should feel big, but you don't have to make it big." Michelle Kaufmann's home designs make the most of what's already there. Photo: Jim Thompson/Destination Productions

RF: What constitutes good design, even with prefab?

Kaufmann: How you make spaces, views, and light. The space should feel big, but you don’t have to build it big. It should feel in scale with our bodies but also feel grand. These tract homes with their punch windows are too big sometimes, out of scale with the body. I am thrilled when I hear people walk through a home I have designed and say “I feel great here. I don’t know why, but I do.” Music to my ears. Goal achieved.

ME: Housing is a commodity valued solely on the number of bedrooms.

Kaufmann: Speaking of commodities, I think we need nutrition labels for homes. How’s the air quality? What’s the water and energy usage? Much like nutrition labels for food, we need more accurate and easy to understand information on products and buildings to help us make better choices. Carbon Emissions labels (including embodied energy) could be on all products, buildings, foods and services.

An instance of the mkGlide house, built in Novato. The interior layout is similar but not identical to the rendering shown above, and also we can see what happens with the interior light with a different compass orientation.

RF: Since you so kindly shared with me much of your other interview material, I’d like to include these unpublished excerpts from a third-party interviewer who asked you about the role of design in building strong communities.

First, how can you take the single-family principle and replicate it at the community level?

it is important to imagine the community rather than just putting together a bunch of homes, as the outdoor spaces are just as important as the indoor spaces. And how the homes open to one another and to the street is critical to providing options for how people can build vital connections with one another, while maintaining some privacy.

If you build a good design, will community come? Or do you think community must be preexistent, and good design flows from that?

There are examples of both. However, most communities that we might think of as being wonderful places organically develop over time. You need good master planning, sustainable design criteria, and phasing. Phasing is key.

Michelle Kaufmann wants to create beautiful “green” homes that would be affordable for everyone. Photo: Bruce Schneider

Do you think beautiful, well-crafted, affordable buildings can create community in and of themselves?

Sea Ranch works really well. But it was built over time. The design criteria has lasted over time as well, because it was based on the climate and the environment rather than a particular style.

Do you think creating a group of a certain type of architecture breeds a certain type of community?

While good architecture cannot solve everything, it certainly can go a long ways to inspiring, empowering and encouraging certain types of thinking and values. Communities that have particular principles of design and sustainability (like Sea Ranch, or Greensburg) or modern design (Sagaponac) will attract a particular type of family, and that is great – because then they will protect, develop and flourish with those values and make sure it is a sustainable community over time.

For example, the people who live in Eichler communities LOVE their homes and their neighborhoods. They are proud, and take care of their homes and help one another in ways that neighborhoods adjacent to them do not. That is the type of community design I want to be a part of – both as an architect, as well as a home-dweller. My best designs come out of me designing places I want to live in.

3 Responses to “Michelle Kaufmann: Phoenix Rising”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Eugene Vicknair

23. Jul, 2010

very interesting. some neat ideas.

Curtis Trimble

12. Mar, 2011

Glad you’re back. I’ve loved your ideas and designs from the beginning. Its exciting to see more.

Kathy Perry

06. Dec, 2014

totally loved your designs… and the good intent that goes along with them…what do you have in the Bay Area? How large are your homes?